Robert Verkerk PhD discusses the discrimination against 4000-year-old medicinal traditions

Western distortion of ancient herbal traditions

The association between humans and plants goes back a very long way. In fact, the association existed long before the evolution of our own species, plants providing a key source of nutrients and phytochemicals for all animals, whether consumed directly or indirectly. When considering the history of herbal medicine, many view it as a tradition that spans some 4,000 or 5,000 years, but of course this time span reflects the earliest known documentation, rather than the earliest usage of plants as medicines.

The Chinese and Indian (Ayurvedic) medicinal traditions are amongst the oldest surviving health care traditions on the planet. Both have a documented history of more than 4,000 years, and both are truly holistic traditions in which consideration is given to the physical, mental and spiritual state. It is an irony that the failing western medicinal model, which is reliant heavily on new-to-nature molecules (pharmaceuticals), now provides the greatest threat to these age-old medical traditions. Western medicine, built on reductionist rather than holistic principles is in many ways the antithesis of the Chinese and Indian systems. Conflict between the systems only occurs if one system is assumed to be superior to the other; and it is the intrinsic arrogance of protagonists of the western medical model that is now creating so much pressure on Eastern medical systems.

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Westerners, largely outside of the medical establishment, have long seen the value of the great Eastern traditions. However, western reductionism—the mindset that is at least in part responsible for the industrial and technological revolution of the last two centuries—has already fragmented the traditions to the point that their overall value on health has been diminished substantially. Acupuncture from China and panchakarma from India have been exported to health spas built for the rich. Yoga, central to the Ayurvedic tradition, is now widely practiced in its physical form in fitness centres, with little attention being paid to its spiritual or energetic dimensions. Meditation is being taught by western personal development gurus, who (with some exceptions) seem happier enough to either ignore advice on the diet or focus instead on their own brands of money-spinning supplements. Last but not least, herbal medicine is being drawn away from the medical herbalist, who traditionally assumed a position of great import within local communities. Herbal medicines are now commonplace on the shelves of the high street health store, pharmacy and Chinese herbalist-cum-clinic. But just how long will these products remain available?

Apart from this incremental dismantling of the traditions, there is another—more insidious—threat to these ancient traditions. It comes in the form of western-style regulation. Recognition that aristolochic acids (AA) in Chinese herbs may be a major risk factor in so-called ‘Chinese herb nephropathy’ and related upper urothelial cancers has been the major trigger for regulation in Europe. The question we must pose is the regulation that has emerged EU-wide to contend with the acknowledged problem of contamination and adulteration, the Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive (EC Directive 2004/24/EC), fit for purpose? The directive was passed in 2004—but has existed since this time in a transition phase, not coming fully into force until April 2011. Is the directive at risk of throwing the baby out with the bathwater?

Ayurvedic medicine

Regulation of dangerous herbs in the EU

Few governments sit idly by when a clear risk associated with a food or herbal constituent is presented. Governments are after all commissioned, amongst other things, to manage risk. On recognition of concerns about aristolochic acids (AA) within Chinese herbs (such as guan mu tong or fang ji), European and many other national governments, including those of Taiwan and the USA, rapidly imposed bans on AA-containing herbs [i].

The problem with AA was revealed in Taiwan and in Belgium about the same time, in the late 1990s. In Belgium, a small number of people who had ingested a cocktail of drugs and herbs prescribed by a slimming clinic were found to develop particular illnesses that were eventually related to the mistaken inclusion of an AA-containing herb. The principle disease associated with the slimming regime was a sub-acute form of interstitial nephropathy that could result in eventual end-stage renal failure [ii]. One of the herbs that was meant to be prescribed by the clinic was Stephania tetandra (han fang ji), but, in error, Aristolochia westlandi (guang fang ji)—which contains significant amounts of AA—was dispensed instead along with the mix of other herbs and drugs. The error was essentially a case of poor identification and traceability of the botanical source.

In the UK, two patients were found in 1998 to suffer end-stage renal failure following long-term usage of AA-containing herbs. The findings were published in the Lancet medical journal [iii] and the authors called for tighter legislation. The Medicines Control Agency (now the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency [MHRA]) duly responded. It imposed an immediate ban on AA-containing herbs and went on to begin drafting a proposal for EU-wide regulation of manufactured herbal medicines. This drafting work resulted in the Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive (often abbreviated as the THMPD).

While a ‘belt and braces’ approach, which ensures an especially cautious approach to regulation is commonplace and often highly problematic to the promotion of natural approaches to healthcare, one has to ask does it go beyond the intended purpose of the legislation and act disproportionately on any particular interests? If a harmful product is banned, do the remaining products of the same type need to be more tightly regulated? To use an analogy; if soft cheeses are found to cause listeria, should soft cheese itself be banned or should steps be taken to reduce the risk of infection by the bacteria within the cheese? The latter is not only a more rational approach, it is also the approach taken by food regulators worldwide. In the case of herbal medicine, does the regulation focus on identifying and restricting other potentially harmful compounds, constituents or contaminants within herbal products, or does it go further than the specific requirement to protect public health?

Traditional Chinese Medicine

Into the mix of facts requiring consideration when building a new regulatory model is also the relative risk of the product. Interestingly, whether looking at European [iv] or US [v] data, empirical data showing harm from Chinese or Indian herbal products reveal are remarkably safe profile. They are dwarfed by the risks from conventional foods, [vi] and made to look insignificant when compared with the risks associated with conventional drugs that now represent probably the fourth leading cause of death in the West. [vii]

About the Traditional Herbal Medicinal Products Directive (THMPD)

The THMPD is essentially a simplified drug licensing system aimed specifically at herbal products (as distinct from individual herbs) for which there is evidence of traditional use as medicines. But, with reasons unspecified, licensed herbal medicines can’t be used for the treatment of anything other than minor ailments, which excludes all the major chronic diseases of western society. Only slightly facetiously, the regulators, likely in cahoots with their pharma paymasters, have limited herbal medicines for tickly coughs and throats.

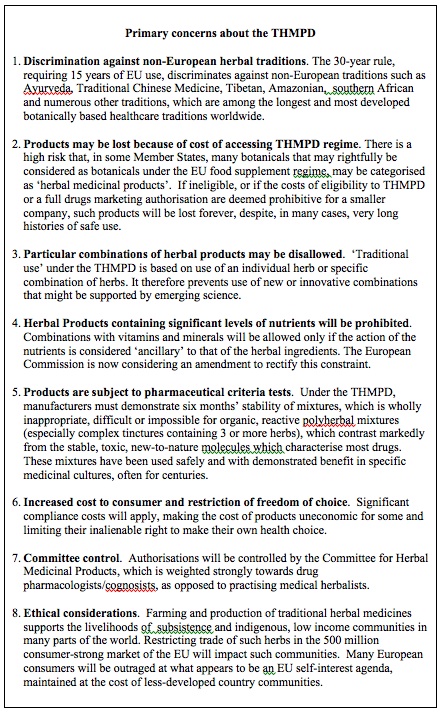

The main and very considerable costs (usually upwards of tens of millions of pounds sterling per drug) expended by drug companies to enable the market authorisation (licensing) of conventional pharmaceuticals are the studies, and especially clinical trials, required to substantiate efficacy. The simplified registration offered by the THMPD comes largely as a result of the waiver of this requirement. However, the requirement for efficacy data is waived only on the condition that 30 years continuous evidence of safe use can be demonstrated, 15 years of which must be within the EU. This eligibility requirement has become known as the ‘30 year rule’ or the ‘15 + 15 year rule’. Since the requirement is for products as opposed to constituent herbs, whereby the exact combination of herbs, at the same relative ratio, are taken into account, the 30 year rule effectively ‘freeze frames’ those products that had already been introduced to Europe by around 1995. It locks out all other products and prevents any innovation or adaptation of the formulations that may result from emerging scientific data or particular disease patterns present in Europe. Even more disconcerting, it actively discriminates against non-European herbal traditions, the great traditions of Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), as well as the diverse traditions of Tibet, Mongolia, South East Asia, southern Africa, South America and elsewhere.

While a small number of cases of contamination or even adulteration (pharmaceutical spiking) of Chinese or Indian herbs have been well publicised, [viii, ix], both the Chinese and Indian governments have taken active steps to control the small number of exporters that had yet to internally enforce sufficient quality standards. In other cases, western regulators have misinterpreted results of their analyses given that in some traditions, such as the rasa shastra practice in Ayurveda, heavy metals are added intentionally. When case reports of patients taking medicines prepared according to the specified practices of rasa shastra are evaluated, credence is given to the Ayurvedic claims that these metals are detoxified through specific methods of preparation.

The THMPD makes patently clear its broad intentions. They are three-fold:

- Harmonisation of requirements on quality, safety and efficacy for herbal medicinal products

- Improvement of pharmacovigilance for herbal medicinal products

- Facilitation of free movement of safe herbal medicinal products within the European Union

While these objectives are generally laudable, they actually allude to some of the problems that are born out of the detail within the directive. For example, when harmonisation occurs across diverse regulatory regimes, there is always a tendency to satisfy the lowest common denominator or the most cautious regulator. When it comes to pharmacovigilance, the directive simply abrogates responsibility to the main European directive controlling conventional drugs (Directive 2001/83/EC) like Prozac, Lipitor and Avastin. And what about the notion of “safe herbal medicinal products”? Is this open slather to exclude any product that might have the slightest potential for causing an adverse effect, even if the risk is only theoretical or includes a minority sub-population that could be catered for by providing a contraindication on the product label? Or, what if the potential risk is infinitesimal by comparison with the known benefit?

As we have found, all these and other issues are very real and point to major problems for the continued development of herbal medicine in Europe (see box)—unless the law is changed (see below).

Just another directive—or a fundamental regime change?

It is easy to see the THMPD as a simple adjunct to the existing regulatory regime affecting botanical products, most of which have been sold to-date as food supplements. But this is simply not the case, particularly when one considers herbal products from the non-European traditions. The date 31st March 2011 has been indelibly marked on the herbal medicine history books as the date on which the transition measures of the THMPD expire—signifying the fact that the following day, 1st April 2011, represents the start of full implementation of the directive. From this date, some member state authorities responsible for medicines, including the UK’s MHRA, will determine that products that contain herbs that have no history of food usage will no longer be allowed to be sold as food supplements. These products will need to be successfully registered under the Traditional Herbal Medicines Registration Scheme (THMRS) in order to continue sale.

The problem is, of course, that products from non-European traditions are hugely challenged by both the eligibility and technical requirements of the THMPD (see box above). An expression of this is the fact that not a single product from either the Chinese or Indian traditional medicinal systems has yet to be successfully registered.

The new directive, therefore, creates a discriminatory regime that forces hundreds of products that have been sold safely within or outside the EU for decades, or in some cases, for centuries or more, to fall between two regulatory stools. They will neither be able to be sold as food supplements, nor will they be amenable to the THMRS.

A legal viewpoint

In March 2010, on behalf of Indian and Chinese interests that would be negatively impacted by the THMPD, the Alliance for Natural Health International (ANH-Intl) sought an opinion from a leading European barrister in law. The opinion came from a barrister at 11KBW, a London based barristers’ chamber of highest repute, with specialisation in the fields of both competition and human rights law, two key aspects affecting non-European herbal products. The opinion made clear that the THMPD, in its present form, runs counter to some fundamental principles of European law.

Right at the forefront of the problems identified by the 11 KBW barrister were three key grounds: proportionality, transparency and fundamental human rights/discrimination. Detailed discussion of these grounds is outside the scope of this article, but suffice to say, it is the disproportionate impact against non-European herbal medicinal products, the lack of adequate disclosure of the technical requirements for registration, and the human rights impacts of the directive that are of prime issue. With respect to the latter, it is of course not only consumers of Chinese, Ayurvedic and other non-European herbs that are impacted, it is also those whose business is dependent on the sale or distribution of these products.

The need for a two-pronged challenge

Over the last three months, ANH-Intl has consulted widely across Europe, in India and in China, with a wide range of interests that will be impacted by the THMPD. This includes the governments of both India and China, key academic institutions in both countries and key representatives of their natural products industries. Despite inter-governmental discussion between both India and China and the European Commission, little has changed. The deadline of 31st March 2011 was after all set in stone back in 2004. Differential interpretations by EU governments caused by the vague and non-transparent language in the directive doesn’t help matters, and works contrary to the principle of creating a single market with minimal barriers to trade.

Our discussions have revealed a surprising commonality of purpose. Not a single party we have spoken to is averse to the principle of legislation and all are supportive of efforts to ensure there is no contamination or adulteration of products. But all are deeply concerned that the THMPD as it currently stands has not been adapted to the unique characteristics of herbal products from the distinct non-European medicinal traditions.

Accordingly, it is highly likely that governments will raise a formal official complaint to the World Trade Organization (WTO). They will be able to demonstrate that a large number of products from the various traditions have been sold safetly in the EU for years, emphasising that the safety record of these herbal products way surpasses that of conventional food. They will then be able to show how the new directive and its associated regime change for botanical food supplements no longer gives many products a suitable regulatory ‘home’ in Europe. They will be able to show how the imposition of the THMPD will devastate trade in safe herbal products through the imposition of unnecessary and very substantial barriers to trade. Realistically, the chances of a positive hearing at the WTO are slim, particularly given the likely predominance of pro-pharmaceutical (anti-natural medicine) views among WTO ‘experts’. Politically, however, a WTO complaint could serve admirably to raise the profile of the issue and garner public support against actions to change the EU’s regime.

At a European level, ANH-Intl has already announced its intention to challenge the THMPD, [x, xi], initially in the High Court in London for the purpose of gaining a reference to the European Court of Justice (ECJ). Rather than seeking to invalidate the directive, the intention of such a challenge would be to force amendment of the THMPD to make it amenable to the non-European traditions for which it was intended, rather than it acting as a barrier to them. The ANH is one of very few non-commercial organisations representing natural health interests that has previously and successfully taken a case to the ECJ (on vitamin and mineral food supplements). [xii] With the support of key interests in two very large nations (China and India) that represent one-third of the world’s population, the decision of the European Court will determine whether justice in Europe is truly fair, or whether it exists largely to foster European protectionism. To rule in favour of the latter would be to offer judgment contrary to stated principles of European law. This suggests reasonable grounds for optimism in a judicial review.

Even more relevant to the ultimate outcome will be whether western reductionism and pro-pharmaceutical interests will get it their way and restrict the 500 million strong European populace from ingesting products related to systems of medicine that have evolved over thousands of years in the East. These medical systems are built on foundations that are barely understood by the western medical establishment. It remains to be seen whether judges, doctors, scientists, policy-makers, consumers and industry players, can come together and see the bigger picture associated with non-European, holistic medical practices such as those of TCM and Ayurveda. It is in the interest of our species to respect and understand (within the limits of the prevailing scientific paradigm) these long-standing and continuously evolving medical systems.

For more information, please see ANH Europe’s Nurture Traditional Medicinal Cultures campaign.

References

(i) Ioset JR, Raoelison GE, Hostettmann K. Detection of aristolochic acid in Chinese phytomedicines and dietary supplements used as slimming regimens. Food Chem Toxicol. 2003; 41(1): 29-36.

(ii) Reginster F, Jadoul M, van Ypersele de Strihou C. Chinese herbs nephropathy presentation, natural history and fate after transplantation. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 1997; 12(1): 81-6.

(iii) Lord GM, Tagore R, Cook T, Gower P, Pusey CD. Nephropathy caused by Chinese herbs in the UK. Lancet, 1999; 354(9177): 481-2.

(iv) Shaw D, Leon C, Kolev S, Murray V. Traditional remedies and food supplements. A 5-year toxicological study (1991-1995). Drug Saf. 1997; 17(5): 342-56.

(v) Bronstein AC, Spyker DA, Cantilena LR Jr, Green JL, Rumack BH, Giffin SL. 2008 Annual Report of the American Association of Poison Control Centers' National Poison Data System (NPDS): 26th Annual Report. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2009; 47(10): 911-1084.

(vi) Mead PS, Slutsker L, Dietz V, McCaig LF, Bresee JS, Shapiro C, Griffin PM, Tauxe RV. Food-related illness and death in the United States. Emerg Infect Dis. 1999; 5(5): 607-25. Review.

(vii) Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998; 279(15): 1200-5.

(viii) Ernst E. Toxic heavy metals and undeclared drugs in Asian herbal medicines. Trends Pharmacol Sci., 2002; 23(3): 136-9.

(ix) Anonymous. Consumption of Chinese herbal products containing aristolochic acid linked to urinary tract cancer. Oncology Times, 2010; 32(4): 46. http://journals.lww.com/oncology-times/Fulltext/2010/02250/Consumption_of_Chinese_Herbal_Products_Containing.17.aspx [last accessed 16 June 2010].

(x) ANH press release: ANH set to challenge EU herb law, 22 March 2010. /news/anh-press-release-anh-set-to-challenge-eu-herb-law [last accessed 16 June 2010].

(xi) ANH press release: Chinese traditional medicine interests express grave concerns over European legislation, 19 May 2010. /news/anh-press-release-chinese-traditional-medicine-interests-express-grave-concerns-over-european-l [last accessed 16 June 2010]. [last accessed 16 June 2010].

(xii) ANH press release: Why the ANH legal challenge on food supplements is a victory, 15 July 2005. /news/anh-release-why-the-anh-legal-challenge-on-food-supplements-is-a-victory [last accessed 16 June 2010].

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences