Patients, understandably, expect their doctors to have their best interests at heart. They must be able to trust them not only with their health, but ultimately, with their lives. Along with this trust comes the assumption that their doctors have at their disposal all the information necessary to ensure the best possible advice on treatments, including about all the options, and their respective risks and benefits. Armed with this information, along with understanding a patient’s needs and life demands, comes the notion of shared clinician-patient decision making – now widely viewed as a worthy substitute for more paternalistic, doctor ‘as god’ rather than ‘as guide’ approaches.

To get to this place, the doctor needs to help create the right environment to allow discussion of all available treatment options, along with their respective risks and benefits so that shared decision-making can occur in the best interests of the patient. Nice in theory, but we hear almost daily of cases that fall short – sometimes very short – of this medical ethic.

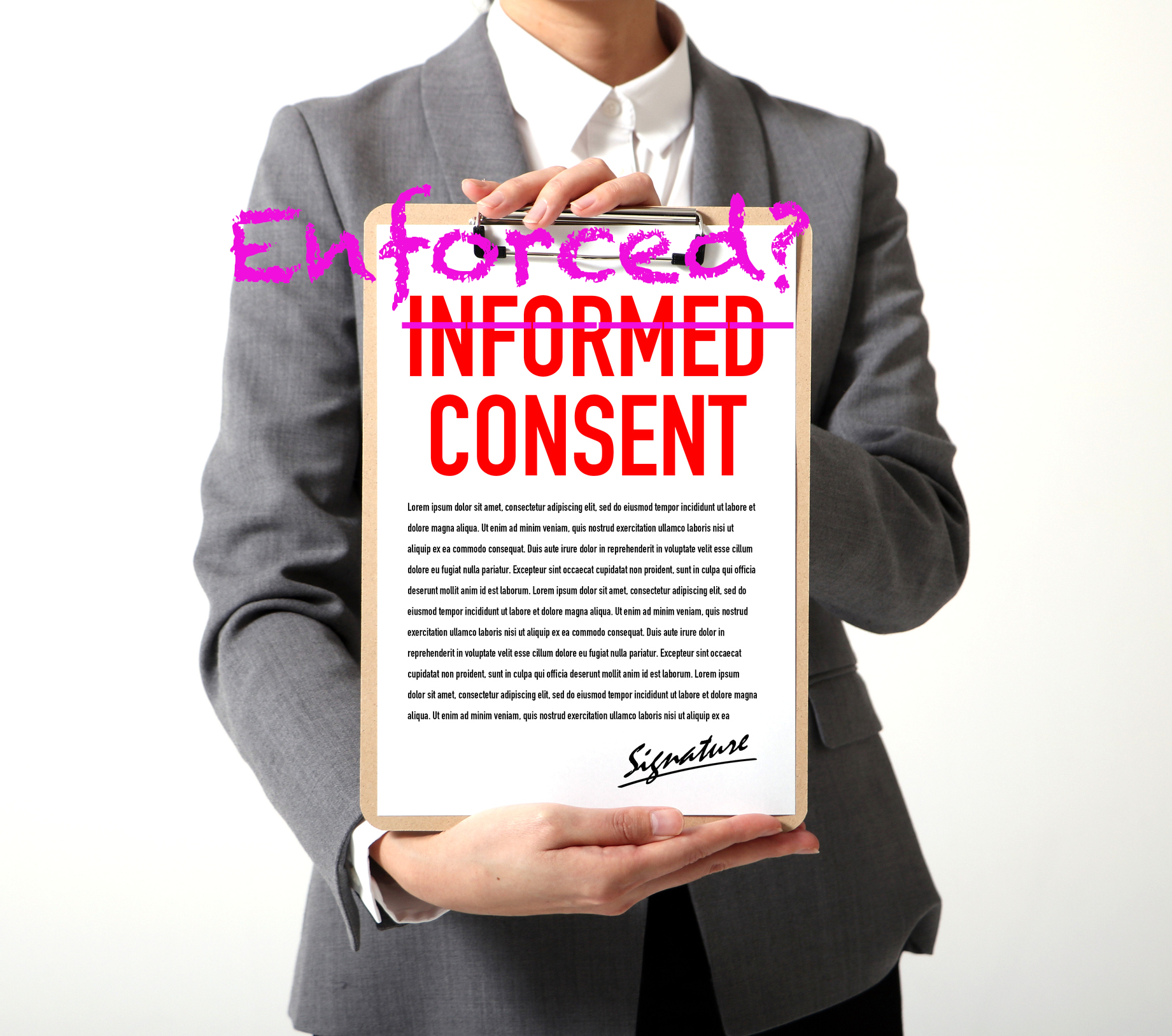

When you have an operation, signed consent is required to acknowledge acceptance of potential risks, yet starting a lifelong drug-based treatment is often treated as being much less important.

All too often, patients are prescribed drug treatments with little or no discussion of their potential negative effects on their health. A case in point is the almost ubiquitous prescription of statins among over-50-year-olds with mildly ‘raised’ cholesterol levels, often without due account being taken of more subtle markers of heart disease risk such as small, dense LDL and oxidised or glycated LDL. Most doctors’ decisions to prescribe statins are made using cholesterol (LDL and HDL) and triglycerides as the only markers, ignoring how well or otherwise their patient is controlling blood sugar with insulin. In short, high LDL levels in those who are not insulin resistant – i.e. those who have good blood sugar control – is not associated with increased heart attack risk.

When patients are offered statins which they might be on for the rest of their lives, very rarely are they told their risk of contracting type 2 diabetes might be increased significantly. A recently published study suggests a nearly 40% increased risk. Nor are they often told what a a thorough analysis of clinical trials has found, as published in BMJ Open in 2015, that their average increase in life expectancy might be just 5.2 days if they’ve had a history of heart disease, or just 3.1 days if they haven’t.

Most mainstream doctors don’t have enough information from standard blood tests to make decisions to offer the best available advice to patients. On top of this, information on possible harms or side-effects are often withheld or under-emphasised, whilst benefits are overstated. The net result is that patients are unable to make a properly informed choices.

What is informed consent?

Seeking informed consent to medical treatments from patients is a fundamental principle of medicine. It’s the process by which a patient agrees to a particular medical treatment be it drug-based, surgical or investigative tests, after considering known risks and benefits of the treatment.

Informed consent should also mean that a patient is provided information on available alternatives. Furnishing patients with information about risks of treatments prior to consent being given as well as being offered information about alternative options are two things that are often omitted within the narrow confines of 10-minute general practitioner consultations.

For informed consent to be valid, there are four basic pre-requisites:

- Consent must be given voluntarily, without coercion or duress

- The patient giving consent must be deemed to have the mental capacity/ability to make the decision

- The clinician must disclose the expected benefits and risks of a given treatment, test or procedure along with the likelihood of those risks/benefits happening

- The patient needs to understand the information they are given

Legal precedent has refined the definition of informed consent in the UK to ensure that “…doctors must ensure their patients are aware of the risks of any treatments they offer and of the availability of any reasonable alternatives.”

Elsewhere, the definition is similar, such as in the US, the European Union, Australia and South Africa.

Misleading information?

Misinformation is rife with biased reporting of risks and benefits of treatments in medical journals and the media fuelled by commercial conflicts of interest. It’s often easier for time-pressed clinicians to turn to information and training from pharma than scour the journals and make educated decisions about actual benefits and risks. This is a reason why independent assessors of clinical data such as Cochrane have been so valued by clinicians – but that independence is now in doubt. Added to this there can be a reluctance to go against mainstream dogma.

But how much info is enough? We’re told repeatedly some patients just don’t want to know, others want to walk out of primary care with a pill of some kind, and some just want to be told what to do. This doesn’t give clinicians a ‘get out of jail free’ card to withhold information or offer limited choices. In fact, research has found that many patients want to be given all available, relevant information and don’t want clinicians to pick and choose what they think the patient should hear.

It’s often difficult for patients to assess risk of harm or potential benefits of a treatment because of the way scientific findings are presented in the public domain. The media and pharma spin doctors typically cite the ‘relative risk’ of a particular intervention or dietary habit. But on its own, without the context of ‘absolute risk’, and without relevant comparisons of relative risk, it’s actually meaningless and can be very misleading! This is well illustrated by the European Food Information Council’s comparison of data about relative and absolute risk in relation to bowel cancer risk and processed meats.

A breach of the Hippocratic Oath?

Imagine a scenario where a morbidly obese patient visits her doctor with chronic knee pain. The doctor prescribes painkillers and anti-inflammatories, which the patient gratefully accepts. The doctor doesn’t discuss other science-based options such as weight loss to relieve pressure on the knee and an anti-inflammatory diet that helps reduce overall levels of systemic, low-grade inflammation. Although the patient has consented to the prescribed treatment, has the doctor failed in his duty to obtain fully informed consent by not discussing alternative options, including science-based non-drug approaches? More than this, has the doctor been negligent in not considering what other health challenges may be faced by the morbidly obese patient, including her increased risk of cancer, heart disease and type 2 diabetes?

Herein lies a systemic failing of primary care – the difficulty of handling comorbidities (multiple conditions or diseases) within the narrow time frames of a primary care consultation window that averages around 10 minutes in most countries and is seen as “a key constraint to delivering expert generalist care.”

Stuck in the evidence mire

Current healthcare systems focus largely on the relief of symptoms as opposed to the creation of health. That’s at odds with an altogether different model that we’ve been developing with our ‘blueprint for health system sustainability’. Treatment recommendations being based on clinical guidelines rely on incomplete and frequently biased evidence that aims primarily to simplify prescribing decisions. Woe betide any medic who dares challenge the status quo!

Become an empowered citizen

You can take an active part in your health care by asking your clinician six simple questions below, before agreeing to recommended treatment(s). Crucially, if you’re not sure, ask for time to consider the recommendations, do some research and don’t be afraid to say no or ask for a second (or third!) opinion. Your health depends on it.

- What benefits do you think the treatment(s) you are recommending will give me?

- Do you know the risks or harms of the various treatment options and how these compare with doing nothing?

- Have you discussed with me the full range of alternatives that are relevant to my condition(s)?

- Do you feel that you have taken into account my needs sufficiently and do you think we have shared the clinical decisions?

- What might happen if I don’t follow the advice you’ve offered?

- Are there any dietary and lifestyle changes, or any other non-drug treatments or approaches, I can use that you think will make a difference?

And finally, we’ve just released a 4-minute video that gives the ‘health creators’ among you an introduction to our health system sustainability blueprint. It explains just how important it is to have a universal language that allows citizens, health and fitness professionals to engage in informed, two-way communications to allow informed choices and, where appropriate, shared decision making.

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences