CBD oil is one of the fastest growing natural health supplements worldwide. Despite a long history of safe use, the growing availability of CBD oil and the exponential growth in the hemp market has resulted in its addition (along with other plant-based cannabinoids) to the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA) novel foods register.

The news has come as a shock to the hemp oil market amid concerns regulators could now sweep CBD (THC-free) products off shelves. It’s no surprise that the European Industrial Hemp Association (EIHA) and UK’s Cannabis Trade Association (CTA) feel a little blind-sided by the U-turn. Both groups attended the European Commission’s Novel Foods Working Group last October, where the EIHA was asked to present on the food use of hemp and hemp extracts.

Why the sudden U-turn by EFSA? Is it because the CBD oil industry’s growth has exceeded all expectations presently eating into pharma sales of painkillers? Or is it because some current market players are not conducting themselves in a professionally self-regulated manner? Maybe there are some genuine safety or quality concerns over some products on the market? Or was there undue pressure from enforcement agencies, which were in turn leaned on by pharma, in the UK, France, Germany, Italy and the Netherlands that forced EFSA’s hand?

Novel or known?

Originally intended to deal with GM foods coming into the EU, the Novel Foods Regulation (1997) has oft been used to impede the introduction of foods or ingredients without a pre-May 1997 history of use in the EU - especially if they compete with drugs. That 1997 date is the date in which the Regulation in its original form came into force. It was updated in 2015 arguably to make the process of obtaining a novel food classification for botanicals that had long histories of use outside the EU simpler and easier.

In order to understand how the Novel Foods Regulation hands the regulators a big stick to beat industry, you need to appreciate that it’s a binary system. The definition in Article 3 forces industry to consider whether you have or have not consumed the food or ingredient concerned “to a significant degree” before the 15 May 1997 cut-off date. You have to prove that with evidence – and that’s becoming tough considering it means accountancy records would need to have been kept for over 20 years. Few do that given financial accounting laws don’t generally require longer than 7 years.

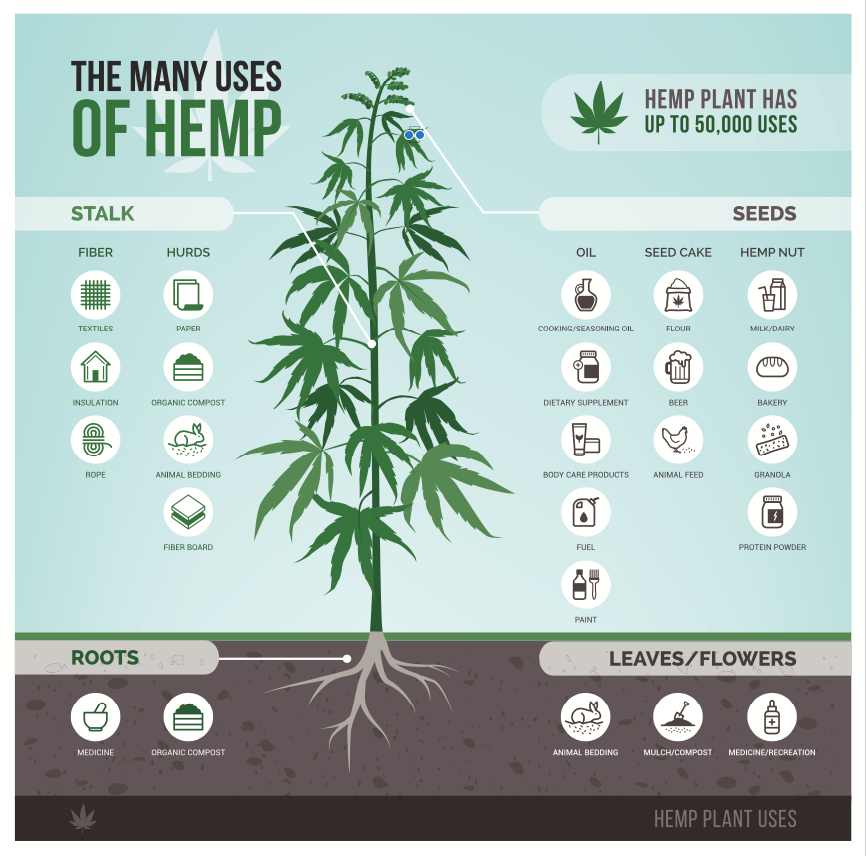

The law doesn't concern itself with the amount consumed - just that sufficiently large numbers consumed it across the EU at any dose. In this regard, we believe there is a clear answer - that hemp seed oil that has long been consumed as an edible oil (as described in the novel food catalogue entry for Cannabis Sativa L.) and contains trace amounts of CBD.

Now let’s look at the issue of composition, not amount.

Article 3.2(a)(vii) of the Novel Food Reg No 2015/2283 is particularly relevant to cannabinoid use in the EU:

"Food resulting from a production process not used for food production within the Union before 15 May 1997, which gives rise to significant changes in the composition or structure of a food, affecting its nutritional value, metabolism or level of undesirable substances".

Via this Article, regulatory bodies are able to argue that there are significant changes in the composition of hemp extracts to make them demonstrably different to conventional hemp oil and therefore novel. For example, extraction methods such as supercritical CO2 extraction that has become all the rage in recent years can make a food ingredient novel because it concentrates certain actives in the product and leaves out others. The result is then demonstrably different enough from the foodstuff to be classified as novel.

The money go-round

The global market prediction for recreational and medical cannabis combined, from 2018 to 2023 is $58.90 billion USD. The global CBD hemp oil market alone is projected to grow from $950 Million USD in 2017 to $2.5 billion USD by 2026. And that’s all for unpatented products outside of pharma control. Serious money causing serious concern.

Add to that a 2016 study which estimated medical cannabis use (extracts including THC) in the US has already cost Big Pharma nearly $166 million USD annually, and could strip upwards of $5 billion USD from profits going forwards.

We know pharma hasn’t got much interest in selling unpatented, naturally-sourced, low cost medicines. With the projected dollar amounts set to erode the over-the-counter (OTC) painkiller market (globally valued at $491 billion USD in 2018), the recent regulatory challenges are understandable.

Naturally effective

Our bodies are replete with endocannabinoid receptors as part of our endocannabinoid system. This plays an important role in the function of our brains, endocrine and immune tissues as well as having a regulatory effect on reproductive hormones and our stress response. The reason CBD oil has such profoundly beneficial effects is because it mimics natural processes that already exist within our bodies. It’s the THC in cannabis that gives rise to the psychoactive effects, but CBD oil as a food supplement contains only trace amounts which isn’t sufficient to create a ‘high’. Unlike many conventional pharmaceutical drugs, there are very few side-effects to contend with, which is why CBD oil has gained such a fast following. Unlike many painkillers on the market, CBD oil isn’t addictive either.

Where’s the level playing field EFSA and national regulators?

The Irish Foods Standards Agency have been very clear that any CBD oil or hemp oil produced by supercritical CO2 extraction is immediately novel. Yet we hear that the UK Food Standards Agency are being more coy on this point, preferring to argue that it’s the composition not the extraction method that matters. All semantics in our view, as it’s the extraction method that defines the composition. It does, however, allow them wriggle room when it comes to other supercritically extracted oils, such as a broad range of vegetable, seed and botanical oil extracts used very widely in foods and food supplements.

Supercritical (CO2) extraction has been in use for decades, but more recently it’s been identified as a much greener extraction method than other methods. Advantages include no thermal degradation, better shelf life due to co-extraction of natural antioxidants, higher purity of extracts, no residual solvents, no oxidation of sensitive compounds as there’s no oxygen in the system, and fewer processing steps. What’s more – it’s natural!

Vegetable oils such as wheat germ oil, green coffee oil, rice bran oil, crude palm oil, essential oils, fatty acids, phospholipids and bioactive compounds have all been extracted supercritically from fruits and vegetables and continue to be so – and are widely sold across the EU and other markets.

How is it then that there isn’t a level playing field when it comes to hemp extracts? Why is it OK for Europeans to consume a supercritical extract of wheatgerm oil that has a higher nutritional value than a cold-pressed oil, and not a hemp oil that is extracted in the same way. This absence of a level playing field is fodder for lawyers – and may need to play a central role in any future legal actions.

If the battle for stevia’s novel food approval is anything to go by, we might well see a draconian hold on the food supplement industry until Big Pharma is ready to release an approved CBD product of its own. Filibustering can work just as effectively in the food industry – especially when a product’s legal use is in question.

The inclusion of cannabinoids on the novel foods register signals a step on a well-trodden path. Restricting use to create demand until the big corporates are ready to release their synthetic versions of effective natural products and steal the market. It’s not just the EU that’s partial to caving to a corporate lobby, it’s already a reality in the US with the advent of synthetic marijuana.

What now?

The boom of CBD oil products in Europe hasn’t fully hit yet, but the market is rapidly expanding and interest is high. It may sound conspiratorial, but the facts would suggest people in suits behind closed doors have decided the market needs knee-capping before it grows any further.

It’s not surprising to find regulatory opposition to a food supplement that has application for so many. But food was and still is our first medicine. The fact that CBD has been consumed in hemp oil as part of the diet for many decades, along with the lack of a level playing field for supercritical extractions, should, in our view, form the backbone of the much-needed defence.

For those who’ve been using CBD extracts and are benefiting from it, we’d strongly suggest you try to buy up at least 6 months’ supply of quality extracts as a minimum as regulators are already moving towards those shop shelves (online and bricks and mortar). Consider signing this petition to keep CBD Oil on the market as a food supplement.

In the meantime, we’ll keep you posted…

Comments

your voice counts

07 February 2019 at 8:43 am

Thank you for this excellent and informative article. As a seller of CBD we will share this with our CBD customers to inform them. Would it be useful for you if sellers like us collected customer feedback and experiences of using cbd without negative side effects in support of it's safe usage and send them in to you? Or raise a petition?

Also, I'd be very grateful if you could advise what you think will happen with this after Brexit?

Many thanks

07 February 2019 at 12:54 pm

I think it is no longer correct to say that 'You have to prove that with evidence – and that’s becoming tough considering it means accountancy records would need to have been kept for over 20 years.' Reg 258/97 has been repealed so we only have to dp what it says in 2015/2283 where Recital 13 and Artcile 3.2 (a)(x) do not say that quantity of use before May 1997 needs to be demonstrated.

My reading of these provisions is that foods used exclusively as or in a food supplements before 15 May 1997 are not considered to be novel foods when they continue to be used as food supplements irrespective of the quantity of use before 15 May 1997. This seems to be a significant departure from the provisions of Regulation 258/97 under which food supplement ingredients have been subject to assessment as novel foods based on quantity of use before 15 May 1997. .

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences