Content Sections

- 1. Are some masks or face coverings more effective than others?

- 2. Should masks be worn by frontline healthcare workers?

- 3. Should masks or face coverings be worn in community settings?

- 4. What can be done to ease the shortage of masks for frontline workers?

- 5. Do masks or face coverings protect those in proximity of the wearer?

- 6. Does the wearer benefit?

- 7. Are there any side effects for the wearer from wearing masks or coverings?

- 8. Are there any benefits in mandating the wearing of masks or face coverings in community settings?

- 9. Is there a scientific argument to make the wearing of masks or face coverings in community settings compulsory?

- 10. How does mask wearing compare with other non-pharmaceutical measures as a means of reducing transmission risk?

Should I, shouldn’t I; should we, shouldn’t we? Will they increase or reduce my risk? Am I duty bound to protect others, or could it increase the risk of others being infected, or make myself more susceptible? Or, even if the science on benefits is too flimsy to know one way or another, maybe I should wear one anyway as an act of solidarity in society’s war against the new enemy? Yes - you've guessed it - we're talking masks.

These are just a few of the questions running around many people’s minds when it comes to the voluntary wearing of masks. In some countries and environments in which a face covering of some sort is required in community settings by law, some are choosing to not venture out much at all - creating new and unknown indirect social and health consequences.

For a quick heads up, the science isn't certain or robust enough to provide definitive answers to any of these questions – that's part of the reason there's such a variety of opinions.

Given we're continuing to scour the literature as it emerges on a wide range of issues around Covid and the predicament we find ourselves in more generally, Rob Verkerk PhD, ANH founder and multi-disciplinary sustainability scientist, and Meleni Aldridge, ANH executive coordinator, also a functional medicine and clinical psychoneuroimmunology (cPNI) practitioner, dive into the uncertain waters surrounding masks in the following discussion in our office.

For those who prefer to read rather than view, you'll find below our our top-line perspectives on masks and face coverings delivered as answers to 10 questions on some of the most studied or relevant aspects of mask wearing when it comes to protecting ourselves and our communities from respiratory viruses and SARS-CoV-2 in particular.

Note: You will see an advertising banner beneath our videos that play off the Brighteon platform (when they are not maximised). This advertising helps support the Brighteon platform that doesn't charge subscribers for their content, is committed to free speech, yet is also respectful of copyright-related law. We'd like to clarify that no advertising revenue from Brighteon is received by the Alliance for Natural Health Intl.

1. Are some masks or face coverings more effective than others?

Yes. There are basically two categories of mask (or respirator) that are commercially available for protection against airborne viruses present in aerosol droplets – medical masks and non-medical ones. Most are disposable, some types are designed to be re-usable after washing or sterilisation. The non-medical ones essentially aim to reduce inhalation of particulates such as dust or aerosols and are classified according to European Standards in 3 different grades, namely FFP1, FFP2 and FFP3. Only FFP2 and FFP3 masks have some, albeit limited ability, to protect against airborne viruses and bacteria. Masks that bear the standard N95, N99 or N100 are compliant with US standards issued by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH), in that they filter out (95%, 99% and 100% of airborne particles). N95 respirators, for which there has been extremely high demand since the arrival of the pandemic, provide more or less equivalent filtration capacity to masks classified as FFP2 in Europe or KN95 in China. Owing to the need to ensure adequate supplies of masks that meet FFP2 and N95 standards or higher, for frontline healthcare workers, many governments have proposed that the public and others outside of healthcare or care home settings use cloth or home-made face coverings. There are very limited data verifying effectiveness of such masks or coverings and it can reasonably be assumed that effectiveness will vary greatly depending on their construction and state.

>>> World Health Organization (WHO) guidance on wearing medical and non-medical masks

>>> UK government mandates face masks on public transport from 15 June 2020

2. Should masks be worn by frontline healthcare workers?

Yes. While there is balance of evidence in favour of reducing transmission rates among frontline healthcare workers who are likely to be exposed to higher loads of virus, there is evidence of medical (N95-type) masks reducing air exchange, suggesting caution should be exercised. One study showed that N95 masks increased emergency medicine doctor’s fatigue levels and decreased the quality and life-saving potential of chest compression in simulated cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). More recent research found over 80% of healthcare workers studied developed headaches which affected their performance at work whilst wearing N95 masks.

3. Should masks or face coverings be worn in community settings?

The results from studies are inconclusive, a view supported by scientific advice to the UK government. A review published in February that considered six randomised controlled trials over 9,000 people found no evidence that either N95 or surgical masks lowered the risk of laboratory-confirmed influenza. The authors therefore said N95 respirators should not be recommended for use by the general public to reduce flu risk – and protect against flu viruses, which are generally thought to transmit more easily than SARS-CoV-2. The European Centre for Disease Control and Prevention (ECDC) suggested in its guidance in April that face masks might be of benefit in busy, closed places and concluded, in the absence of evidence one way or another that the “…use of face masks in the community should be considered only as a complementary measure and not as a replacement for established preventive measures, for example physical distancing, respiratory etiquette, meticulous hand hygiene and avoiding touching the face, nose, eyes and mouth”.

In the real world, there are concerns that transmission risks may increase as people are more likely to touch masks and their faces, increasing risks of transmitting virus particles both to themselves and to others. There’s little or no benefit of their use in uncrowded outdoor spaces where people are able to practice considerably more than 2 metres of social distancing.

For many, the wearing of masks is a display of public spiritedness and solidarity showing they care about others around them and that they are providing protection against infection. However, in our view this is a feeling that is certainly open to exploitation if people are made to feel guilty about not wearing a face covering. Amplified by a paper published this week based on a modelling framework, that baldly states: “A key message from our analyses to aid the widespread adoption of facemasks would be: ‘my mask protects you, your mask protects me’”.

Wearing a mask may also confer a sense of security that allows people to go out and about again as lockdowns are lifted with less fear. Despite their popularity during the 1918 flu epidemic many questions were raised over their effectiveness. The difficulty of getting people to follow basic hygiene protocols let alone wearing masks properly was highlighted during that epidemic. Despite all our developments in modern hygiene how diligent will people be today?

4. What can be done to ease the shortage of masks for frontline workers?

Demand for masks and respirators for frontline workers has led to global shortages and expectations that masks may be reused and/or worn for extended periods of time. Using dry heat of 70oC for one hour effectively decontaminated N95 respirators, while heating or the gentle application of surface disinfectant sprays was found to effectively disinfect a range of masks with little damage thus extending their life and the number of times they could be used.

In the US, the Boston Children’s Hospital created a do-it-yourself reusable respirator with N100 filtration using an anaesthesia mask, inline ventilator filter and elastic straps. The makeshift respirator can be decontaminated by either washing it with soap and water or disinfectant. The authors caution that the facemask is not approved by NIOSH, but suggest during a crisis when face masks are in short supply such an option may be a viable alternative.

5. Do masks or face coverings protect those in proximity of the wearer?

Probably, but only if the mask or covering is relatively fresh, and mainly in the event of aerosols being generated during coughing or sneezing or when speaking. Previous studies indicate that a range of masks provide some protection against infection. Medical masks provided the highest protection with homemade cloth masks providing the least protection. A review of randomised controlled trials found respirators to be the most effective protection for healthcare workers when worn continuously throughout a shift and that mask use by people without symptoms of infection could provide protection to others.

6. Does the wearer benefit?

Yes, probably marginally, in best case scenarios. Facial coverings or masks may provide limited protection against the inhalation of infectious droplets from others, although evidence in this area is weak and sometimes inconclusive. Much depends on the quality of the mask, its filtration capacity, particularly given the extremely small, sub-nano size of SARS-CoV-2 particles, its fit, how long its worn for, and what the concentration of viral particles is to which it’s been exposed.

7. Are there any side effects for the wearer from wearing masks or coverings?

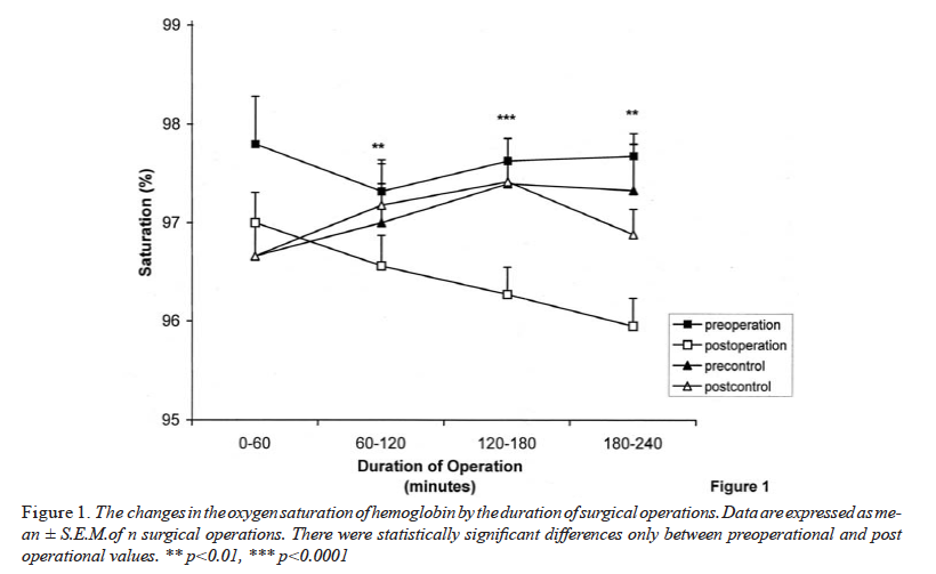

Yes – many as you may have seen discussed in our video above. Surgical masks of the N95 and FFP2 standard reduce airflow and so increase breathing resistance. A study of 14 adult volunteers in Singapore published in the Annals of Occupational Hygiene found that N95 respirators caused 122% and 126% increases in inhalation and exhalation resistance, respectively, with an average 37% reduction in air exchange volume. Another 2011 study showed that medical, surgical and dental masks typically cause a small but significant increase in core temperature that may cause discomfort and adversely affect behaviour. Their use in surgery has been found to reduce blood oxygen saturation; the longer the use, the greater the reduction. Such changes in blood oxygen concentration in haemoglobin could have negative effects on cardiovascular, psychological and motor function along with a reduction in immune system function, putting the user at greater risk of contracting covid.

We have tested various masks in our own office and measured blood oxygen saturation levels using a pulse oximeter whilst wearing and without. Typically finding a 1-4% reduction after a mask has been used for over an hour, depending on the individual and the type of mask used. We also noted that our pulse rates increased by 10-20 beats per minute to compensate for the resistance and reduction in air exchange, which places stress on the body. Masks have been found to significantly increase the risk of headaches in healthcare workers — one of our team suffered similarly after wearing a mask for over an hour.

For healthy individuals under 70, blood oxygen saturation levels vary between 95% - 100%. As we age, levels tend to decrease to around 93% to 95%. Individuals suffering from COPD can experience levels as low as 88-92%. However, once your oxygen saturation drops below 90% you risk becoming hypoxic, which poses a significant risk to health. Individuals infected with the SARS-CoV-2 virus are at higher risk of silent hypoxia, a condition, which potentially could unknowingly be exacerbated by wearing a mask.

Source: Beder A et al. Preliminary report on surgical mask induced deoxygenation during major surgery. Neurocirugia (Astur). 2008;19(2):121‐126.

As masks become damp during prolonged usage, they can become a reservoir for a range of different pathogens. Breathing more deeply could result in bacteria and viruses being drawn more deeply into the lungs thereby increasing the risk of becoming more seriously ill.

8. Are there any benefits in mandating the wearing of masks or face coverings in community settings?

In our view, no. The mandating of mask wearing has its roots in fears over transmission of the virus from asymptomatic carriers. However, this transmission route has been plunged into debate by the head of the World Health Organization’s emerging diseases and zoonosis unit, Dr Maria Van Kerkhove during a recent press briefing. The science is unclear in this area with research ongoing.

Masks available to the general public tend not to fit well, aren’t worn or disposed of correctly, with the benefits of homemade face coverings being difficult to quantify. People wearing masks tend to fiddle with them and then touch their faces more – a habit that is associated with increased infection and transmission potential. If face coverings are mandated, it will require diligent adherence to basic hygiene procedures such as hand washing or use of hand sanitisers to ensure that they do not exacerbate transmission.

9. Is there a scientific argument to make the wearing of masks or face coverings in community settings compulsory?

We think not. Think about an older person who has low oxygen saturation by virtue of her age and additionally has a lung disease such as COPD. That would typically give a blood oxygen saturation level (SpO2) of around 90% which is borderline hypoxic. If this person was forced to wear a mask to take a bus or train ride to do her weekly shopping, the resultant drop in SpO2 could endanger her life or those of others – not from the virus but from hypoxia. It would also increase her vulnerability in the event of being infected.

It also appears that the deaf or hard of hearing that need to lip read to communicate have been completely overlooked. Additionally, the ensuing social isolation from losing an essential element of communication - non-verbal somatic cues from seeing each other’s faces. This is a particularly important element of a child’s development as our neural networks are keyed into facial expressions and somatic cues to convey safety and security, as well as emotional learning. It’s not just about the prevention of transmission, we also have to take into account human physiology and behaviour and the impact to mental health from further social isolation.

10. How does mask wearing compare with other non-pharmaceutical measures as a means of reducing transmission risk?

In a recent media briefing the Director general of the WHO stated, “...masks on their own will not protect you from covid-19”. Masks do not replace basic hygiene measures such as handwashing and physical distancing. We agree.

>>> If you’d like to sign a UK petition to prevent the mandatory use of masks, sign this petition.

>>>Find out more at ANH-Intl Covid Zone

Comments

your voice counts

12 June 2020 at 6:02 am

I just assumed this was all part of the plan to herd (and train) everyone toward accepting a mandatory vaccine. i.e. make life as difficult and hellish as possible and then say if you want the nightmare to stop "take the (experimental) shot".

Politicians aren't bumbling idiots falling over themselves to represent the people as best they can; rather they are creating policies that seem idiotic unless you realise their true constituents are big pharma and big tech (surveillance).

12 June 2020 at 10:45 am

Thank you for this video. I live in Belgium where mask wearing is mandatory on public transport and in some public areas such as busy shopping streets and shopping centres. I have long-term chronic fatigue and my energy levels are poor. I find wearing a mask very difficult and find myself breathing through my mouth - surely not a good thing, I have trouble controlling my temperature so am dreading hot weather wearing a mask. I also find my anxiety levels increasing with the mask and am finding myself avoiding places where I need to wear a mask thus limiting my already rare trips outside or taking a car rather than public transport! Having a naturally quiet voice, I find myself having to constantly repeat myself so people can hear me - something else that is very tiring with limited energy. In fact, I find myself feeling quite distressed sitting here typing this and thinking about wearing a mask.

I also fear that this is going to become a new norm and anyway not wanting to wear a mask is going to be branded anti-social and selfish.

Thank you again for presenting a thorough and thoughtful review of another public health situation which I feel has been rushed into more for the authorities being seen to do something without any deep thought on the issue rather than for any proven efficacy.

12 June 2020 at 12:28 pm

The masks, the social distancing, the fear is all 'social engineering' and the controllers know exactly what they are doing!

I fully agree with the previous coment, this is going to be the future for all of us who don't comply with the 'new normal'.

I have just been forced to use a face mask for a visit to my GP this morning, Boots would not sell me one mask, I had to buy a box at a cost of £30, I wonder how many politicians have shares in the face mask companies?

This is medical tyranny and mandatory vaccinations to free us from our chains is medical rape!

14 June 2020 at 8:31 pm

Taking COVID-19 out of the equation, this is all about control. Divide and conquer. From what I read (and I read a lot about this) the whole issue has been purposely blown out of proportion. There are serious discrepancies in the numbers and the science as ANH point out. The mainstream media is parroting the official propaganda and most scientists that have differing view from the official narrative are not being considered or heard. The examples set by Sweden, Japan, Taiwan are not being discussed or considered. And then there are just plain lies. For example the BBC allowing Bill Gates to claim he is a health expert with no challenge to his assertion. There is more to this plan-demic than meets the eye.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences