Content Sections

A lot of people today, especially older people who are both more likely to be sick and are often more concerned about their health, use natural herbs and supplements as well as drugs they’ve been prescribed by their doctor. It’s therefore entirely reasonable that scientists should see what might be going on in terms of any untoward herb-drug or supplement-drug interactions. Or even supplement-herb interactions.

This week a study was published by the University of Hertfordshire that attempted to shine a light on this issue. Sadly, in our view, it does quite the opposite. And we’re concerned it might do more harm than good.

It’s already triggered reactions from the media warning people not to mix herbs or supplements with drugs. Sky News, the Telegraph and the Independent are just a few who picked up on the study. And even the British Association for Nutrition and Lifestyle Medicine (BANT), one of the main UK associations looking after the interests of nutritional therapists, has reacted to it. But a bit more on that below.

The essence of our concern is this: The study only included 155 responses out of 400 questionnaires sent out to patients on one or more prescription meds in two GP practices. One involved mainly white, older people in a rural village in Essex, the other came from a North London, urban practice with a larger black, Asian, and minority ethnic (BAME) population. The questionnaires usefully collected information on what herbs, supplements and meds the respondents were on. And while there is a possibility of negative drug interactions in a small number of the respondents (16 of 155), there wasn’t enough information to indicate what doses were involved. More to the point, the abstract wrongly states that 32.6% of the participants were at risk of potential adverse effects – when in actual fact it was 32.6% only of 33.6% of the participants who concurrently consumed herbal medicine products and food supplements with prescription medicines. That's 16 potentially at risk of drug interactions are therefore just 10% of the participants, not 32.6% as suggested. This misrepresentation has been amplified through the media – and we’ve written to the journal, British Journal of General Practice, to try to get the error corrected.

What’s more, there’s no suggestion that the herbal medicines or food supplements might be providing benefits or filling nutritional gaps. That’s something of an oversight when you check out the latest UK dietary surveys that show that significant numbers of the population are deficient even to the standards of the lowly lower reference nutrient intakes (LRNIs).

The ability of people to manage their own health is a very important part of trying to help our society to shift from a disease-focused society that pops pills (synthetic or natural) after it’s generally too late – to one that’s fully engaged in health creation. That’s what our sustainability blueprint is about. So we’re somewhat dismayed to see this misconstrued University of Hertfordshire study used as a mechanism to tell the British public that they shouldn’t take food supplements unless a trained health professional advises them to do so.

And what about those who want to use natural methods of health – and who can’t afford to see a private practitioner with expertise with herbs or supplements? Is self-care by natural means off the menu? Should anyone who can’t see a private natural health professional be limited only to drugs prescribed by their GP? We think not.

As it's #ThrowbackThursday we're sharing one of our previous articles on why we may need supplements and their benefits.

Vitamin supplements – rebutting fake prejudice

We all know the theory that we should be able to get everything we need from our food. Evolution tells us this must be the case. The much more relevant question, however, is: do most of us actually get everything we need from our food?

In recent news Sian Williams, the presenter, journalist and breast cancer survivor on UK ITV’s ‘Save Money: Good Health’, stopped taking supplements after a blood test showed the vitamins weren’t making a difference. Williams, along with a group of pensioners from Eastbourne, were asked as part of the TV programme to give up their supplements for a total of six weeks. Despite most of them ‘feeling unwell’ during this short period, the big reveal was a scientific let down. Everybody’s tested vitamin levels were within the ‘normal’ range. This left many questions: What did the programmme’s scientific advisors consider normal? How do these normal ranges differ, if at all, from ‘optimal’ ranges? What was the nature of the blood tests performed for each nutrient (e.g. plasma, erythrocytes)? Why didn’t they ask the participants how they felt?

The fact is, this TV programme signalled the trigger for plenty of vitamin bashing news in recent days. Dr Potter from The Times even commented that vitamin supplement takers were “among the healthiest in society“. Surely that doesn’t mean they’re either worthless or dangerous, Dr Potter? Expensive wee stories, like that in the Daily Mail, were naturally par for the course.

But food supplements faced a double whammy of attacks. They received further bad press after publication of a peer reviewed paper that ostensibly revealed the “hidden dangers” of food supplements. In actual fact, the story was spun out to the vitamin bashers in the media when actually it’s a non-issue for reputable companies, manufacturers and contract manufacturers in the UK and through most of Europe who adhere to tight quality control standards. As our founder, Rob Verkerk PhD told Nutraingredients this week, it is an issue for a very small number of imported products, most of which are sold via the Internet and produced by cowboy operators.

How much do we need?

There are four main ways to find out if someone is getting enough of a particular micronutrient. These are:

- Blood tests: Measuring levels in particular blood compartments and comparing the results for specific vitamins or minerals with reference ranges (which can themselves vary).

- Functional testing: Using a range of clinical tests, such as those widely used in functional medicine or clinical nutrition, that assess specific key functions within the body that are mediated by micronutrients. Such testing will be more likely to take into account individual needs, especially where these are significantly higher (or lower) than the average person.

- Evaluating health status, function and resilience of an individual. This in essence is using a more objective approach to assessing how someone feels, especially after changing their dietary patterns. Most people benefit from having a qualified healthcare professional in a relevant discipline or modality undertaking the assessment and then offering suggestions, the effects of which are monitored over time.

- Comparing dietary intakes against reference values. These reference values might be Estimated Average Requirements (EARs), Dietary Reference Intakes – or even labelling Nutrient Reference Values (what used to be called Recommended Daily Allowances or RDAs) in diets that might be regarded by nutritional experts as ‘healthy diets’. However, these reference values don’t cover optimal intakes. To establish optimal levels of intake, it’s often useful to look at what might be consumed when considering dietary patterns that nutritionists would agree are associated with long, healthy lives.

As it happens, we published a peer-reviewed paper in 2010 that critiqued the EU’s proposed approach to establishing maximum permitted levels of vitamin and mineral food supplements. In the paper, Dr Rob Verkerk took the UK’s healthy eating guidelines and calculated vitamin and mineral intakes for ‘a typical day of healthy eating’, drawing the vitamin and mineral contents from the very comprehensive data in the USDA Nutrient Reference Database.

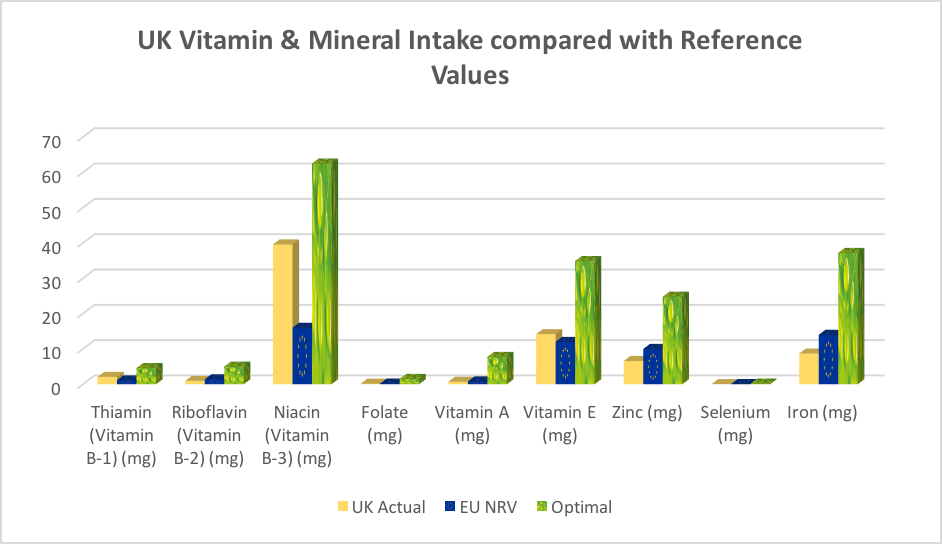

What we’ve done in Figure 1 below is compare these optimal intakes, with the labelling reference value (EU Nutrient Reference Values or NRVs that you find on food labels) and the amounts of selected vitamins and minerals actually being consumed by the average adult in the UK (based on the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey or NDNS).

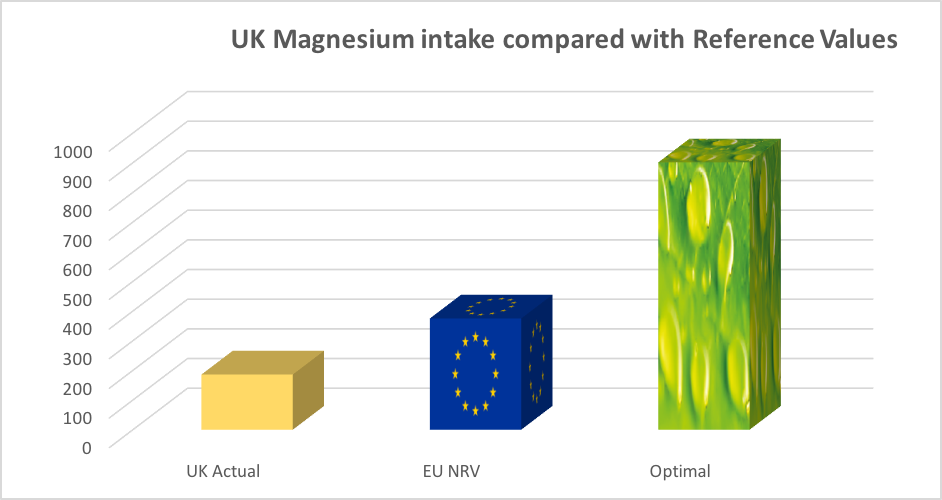

We separated the magnesium data because the actual intakes in milligrams per day were so much more than the other micronutrients.

Check it out…

A.

B.

Figure 1A and B. Comparison of actual intakes, labelling reference values and optimal intakes for selected vitamins and minerals (actual intakes based on NDNS data 2010, EU nutrient reference values (NRVs) from EU Regulation 1964/2011, and optimal intakes from Verkerk & Hickey (2010). Figure 1A shows comparisons for 6 vitamins and 3 minerals, and Figure 1B comparisons for magnesium only.

The results reveal a shocking discrepancy between actual amounts of selected vitamins and minerals consumed and the optimal amounts, as found in a healthy day of eating. The intakes only look acceptable when you compare actual intakes with labelling reference values – which for years – clinical nutritionists, functional medicine practitioners and nutritional therapists have argued are far from optimal!

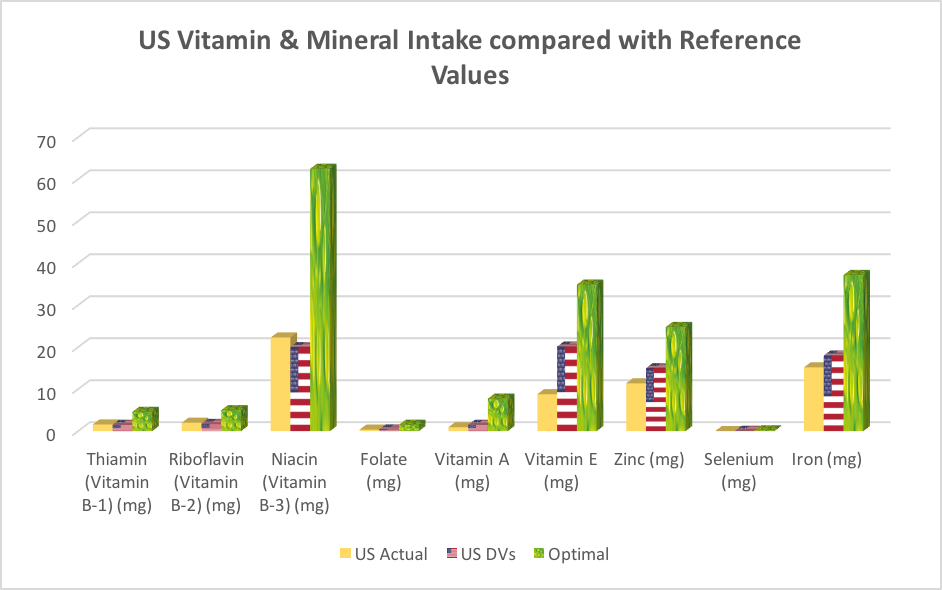

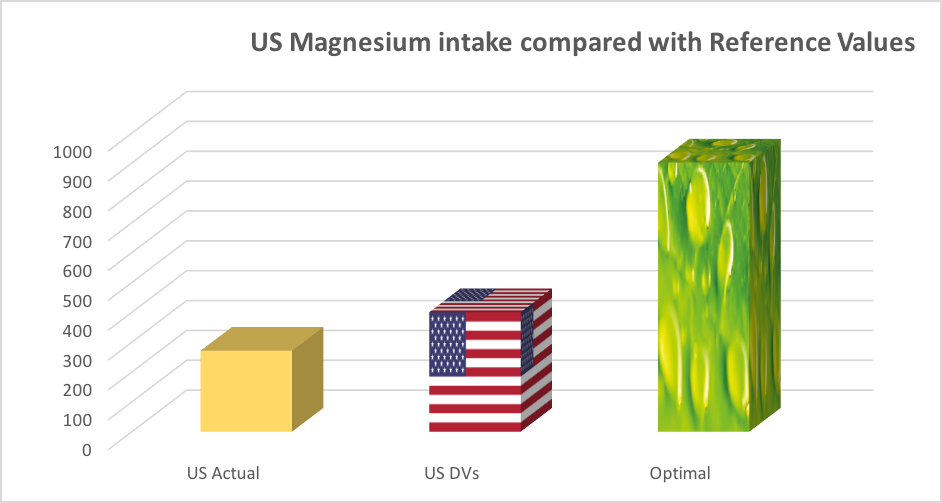

We’ve done a similar thing with US data. We’ve taken actual data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES), and then compared these with the labelling ‘daily values’ and again, with the same optimal intakes we determined from a typical day of healthy eating using micronutrient contents in the USDA Nutrient Reference Database (see Fig 2).

A.

B.

Figure 2A and B. Comparison of actual intakes, labelling reference values and optimal intakes for selected vitamins and minerals (actual intakes based on US daily values (DVs) from NHANES data 2010, US daily values (DVs) from The Food and Drug Administration and optimal intakes from Verkerk & Hickey (2010). Figure 2A shows comparisons for 6 vitamins and 3 minerals, and Figure 2B comparisons for magnesium only.

The results were equally shocking! Once again actual intakes are similar to the daily values, but far from the optimal levels recommended by clinical nutritionists, functional medicine practitioners and nutritional therapists! In other words people are not achieving the recommended levels of nutrients in their daily diets, let alone consuming enough to promote optimal health.

The differences in actual intake, recommended intake and optimal intake levels for magnesium for both the UK and US were startling (Figures 1B and 2B). Magnesium is a vital mineral used by every organ in the body, especially the heart, muscles, kidneys and gut. Deficiency in magnesium is powerfully associated with increased risk of the number one cause of death worldwide, cardiovascular heart disease. Magnesium helps to activate enzymes, contributes to energy production as well as helping to regulate levels of calcium, copper, zinc, potassium, vitamin D amongst other nutrients in the body. People eating a Western-style diet, those drinking too much coffee, fizzy drinks or alcohol or suffering prolonged stress or engaged in intensive physical activity or exercise, have much higher requirements for magnesium, so the low levels shown in the charts should be a real cause for concern.

A lot of people simply don’t have the time, money or inclination to eat an optimal ‘healthy’ diet, day in and day out.

We know from the UK National Diet and Nutrition Survey that only a third of the population are achieving the five-a-day fruit and vegetable target. Even the dietician on ‘Save Money: Good Health’ pointed out the need for vitamin D supplementation, particularly in view of the increasing cases of rickets worldwide.

Due to over-farming, monocultures and the intensive use of pesticides, the soil in which our food is grown has become depleted of minerals. Fruit and vegetables by the end of the 20thcentury likely contained an average of 20% fewer minerals than they did in the 1930s. In some cases, the losses over this period may have been as high as 70%. Further depletion occurs owing to long post-harvest intervals, food storage systems and food processing. It is also evident that our nutritional requirements may be increasing owing to the burden of environmental toxins to which we’re exposed, including air and water pollutants, solvents, cleaners, plastics and moulds.

Who needs these supplements?

We are not just talking about vitamins and minerals, people may need to supplement protein, essential fatty acids, phytonutrients and nucleotides. Most of the meat that we consume is now grain fed, which is very low in antioxidants and fatty acids, and hardly anybody eats organ meats, a rich source of nucleotides, which have important effects on the growth and development of cells, particularly important for the health of our gut and immune system.

The over-55’s age group are among the largest users of supplements. As we age, our need for nutrients increases due to a reduction in our ability to absorb them. Enzyme and hydrochloric acid production declines (i.e. hypochlorhydria) with age, making it difficult to break down and absorb nutrients from food. So-called ‘inflamm-ageing’ increases too. Older people are often on multiple medications (polypharmacy), which can also can interfere with this process. This means older people benefit from specific supplements in their most bioavailable form.

Knowing somebody’s genetic makeup can indicate whether he or she would benefit from supplementation. For instance, adequate folate is essential for the fundamental process needed to create new DNA, RNA and cells (one-carbon metabolism). Methylation is a vital process to ensure healthy DNA and gene expression which in turn are crucial determinants of our health. Under- or over-methylation can leave us susceptible to a range of health issues such as fatigue, poor cognitive function, reduced detoxification and chronic conditions such as cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease. Certain B vitamins, in particular folate, vitamins B12 and B6, along with zinc, magnesium, copper and zinc are key co-factors when it comes to maintaining healthy methylation and energy-yielding cycles in the body that are essential for all physiological, metabolic and immunological processes.

In theory, getting all your nutrients from food is the ideal, but, for the vast majority, virtually impossible in practice. Whilst everybody should focus on consuming a diverse, nutrient-dense diet first and foremost, that’s rarely enough anymore and high quality supplementation with the right balance and range of nutrients are beneficial to most if optimal health is the goal.

Call to action

- Know your intake or your levels of micronutrients, especially if your health is less than par. Visit a functional medicine practitioner or nutritional therapist to understand better how your health status may be improved by changing your diet, your lifestyle and, potentially, providing appropriate supplementation

- Consume a nutrient-dense diet following the 10 pointers as per our Food4Health guidelines.

- Counter prejudice against vitamin supplements by circulating articles such as this among your friends and contacts to demonstrate that most people’s vitamin, mineral and micronutrient intakes are well under those associated with optimal dietary intakes of conventional foods.

- If you like what you read, and you value what we do, please make a donation to ANH International. Our supporters are the life-blood of the work we do at ANH-Intl, for your benefit.

Comments

your voice counts

28 September 2018 at 11:13 am

An excellent article, I was told all this 30 years ago by Dr. John Lester who was 30 years ahead of his time, he checked my vitamin and mineral levels (Biolab) and put me on most of these plus essential fatty acids, which hugely improved my state of health, I am still taking them, and am extremely healthy and energetic for my age!

01 October 2018 at 6:53 pm

As I celebrated my 80th Birthday last month my GP said to me - Judy you were right all along about Functional Medicine. Mind you, it was the brilliant Integrated Doctor who helped me learn how to manage my health with the help of vitamins and minerals some 20 years ago when diagnosed with M.E. I take these to this day and consequently am on the minimum of drugs and costing the Government virtually nothing and keep being told how young I look. My previous GP had told me there was nothing that could be done to help with my M.E. and I must learn to live with it. RUBBISH. My current much loved GP has taken on board what Dr Rangan Chatterjee is recommending in his book The 4 Pillar Plan. Is there light at the end of the tunnel at last?

02 October 2018 at 8:20 am

Belated birthday wishes Judy, I hope you had a lovely day. It's great to hear how well you're doing and that you're continuing to spread the message about the benefits of natural healthcare.

Warm Regards

Melissa

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences