Content Sections

“There is no definition of a mental disorder. It’s bullsh*t. I mean, you just can’t define it.”

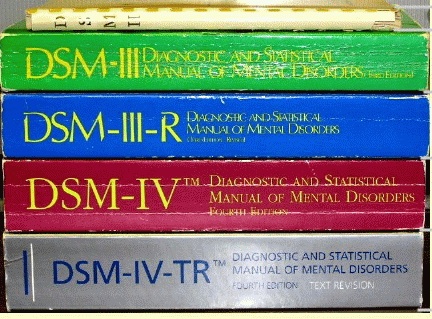

This little nugget is from the mouth of Allen Frances MD, the lead editor of the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV), the ‘psychiatrist’s bible’, who also claims that the DSM is “padding the bottom lines of drug companies”.

We think the DSM acronym might better represent a ‘Diabolical System of Medication’. But are we being too cynical?

The Lancet wades in on the debate

Following this discovery and an article in the esteemed medical journal The Lancet in February 2012, we decided to explore the Lancet’s concerns about mental health diagnoses and factors surrounding it a little further.

The Lancet’s article followed a decision by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) to list grief as a mental illness in the upcoming fifth edition of the DSM (DSM-5). Grief? Surely that’s a perfectly normal human reaction to a traumatic, often life-changing, event? On this point, we and the Lancet are thankfully not alone in our pleas for grief to be treated as such. CNN reported on it, as did the Mail Online, Reuters and many more news portals. In earlier editions of the manual there has existed a ‘grief exclusion’ that meant that anyone that had experienced a loss could not be diagnosed as having depression for a year (in DSM-III), 2 months (in DSM-IV) and it is due to reduce even further to just 2 weeks in DSM-5!

Get over it — or else…

So, hear this: unless we get over our heartbreak in 2 weeks or less, we have the possibility of being diagnosed with a mental disorder if we decide to seek support from our local GP. And of course there is a pill – or a suite of them – for treating this particular ill! Psychological drugs are a veritable cash cow for the pharmaceutical industry, especially when you have an army of doctors out there prescribing them for healthy human reactions to life events.

A further look at the DSM

We have written before on the topic of the DSM and the many criticisms of it for disregarding credible scientific evidence when listing new mental illnesses. Some of the listings are bordering on the ridiculous, such as shy people being diagnosed with “Avoidant Personality Disorder” (click on DSM-IV) for which there are recommended treatments such as monoamine oxidase inhibitors or fluoxitene (Prozac to you and me).

Prozac: a recommended treatment for being 'shy'

The DSM, branded as a “dangerous public experiment that could turn normal human experiences into an epidemic of mental illness with healthy people being drugged”, is believed to be a factor that has led to over-prescribing and therefore increased use of drugs such as anti-depressants and anti-psychotics. Even Frances himself admits that they made “mistakes that had terrible consequences” in the DSM-IV. These mistakes lead to a massive surge in the diagnoses of, and consequential drug prescriptions for, autism, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder, and bipolar disorder.

The American Psychiatric Association’s pharma ties

It’s no surprise to find that both of the so-called philanthropic arms of the APA have industry ties—the American Psychiatric Foundation (APF) has 4 out of 15 members of its board of directors who are high-level executives from pharmaceutical companies that either manufacture the medications recommended by the APA or have products in development specifically targeted for mental disorders. Then to top it off, the American Psychiatric Institute for Research and Education (APIRE) has 9 out of 16 members tied to industry.

A BCC Research report approximates the “global mental health pharmaceutical market can be estimated at $80 billion in 2010…” and “…to reach a value of $88 billion in 2015”. No surprise when the number of mental illnesses that doctors have to choose from is increasing exponentially — all of them suggesting pharmaceutical intervention. Martin Whitely, a West Australian Labour MP and anti-ADHD medication campaigner, believes that ''under the new criteria it's almost harder not to get diagnosed with ADHD than it is to get diagnosed with it''. Is that the not-so-dulcet sound of coins we hear as the DSM hits the doctors’ desks?

A pill for every ill?

As you continue to wade through murky pharma waters, you realise that nothing is sacred. People are conditioned to believe that by popping a pill, anything can be fixed in record time with little personal discomfort or effort. A pill for this and a pill for that and you’re back in the saddle in no time. No need to process those uncomfortable emotions. But what of the possible side effects and long-term risks, both directly as a result of toxic, physiological reactions within the body and, importantly, in relation to unhealed emotional states? And do drugs such as anti-depressants actually work most of the time in most people? When we say work, we of course mean heal. Not just wrap you in a sense of ‘cotton wool’, distancing you from your problems and delaying your emotions (or should we say symptoms), until such time as you come off the drugs.

Research shows that although medication can relieve the symptoms of depression, those treated with anti-depressant drugs are more likely to relapse (72.6%) once off the medication than those treated with cognitive therapy (30.8%). Why is it then that according to a report from MedCo, a pharmacy benefit manager, one out of every four women (in the US) has a prescription for some form of mental health medication — for depression, ADHD, anxiety or some other emotional crisis? Especially when a) the person might not be ill, b) the illness might not really exist and c)the drugs might only provide a short-term fix.

A 15 minute video was aired recently on US TV news channel, CBS, and covers Harvard Medical School Professor, Irving Kirsch’s findings that antidepressants are no better than dummy (placebo) pills. He explains that it doesn’t really matter whether the patient takes antidepressants or a placebo; they still improve. He feels the real benefit not only comes from being given something that they expect to help — not the chemicals in it — but also from someone asking them about their symptoms and listening to their answers.

Towards the end of the video was mention of the UK’s National Health Service (NHS) and its guidelines for treating depression. The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE) reviewed the evidence for the effectiveness of treatments for depression and anxiety and consequently recommended cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT), counselling and physical activity. Only when the depression entered the upper levels of severity were pharmaceutical products mentioned. Whilst we’d like to see these guidelines going further into nutrition and lifestyle modifications, those of us in the UK seem to be significantly better off than US citizens, who are still at the mercy of guidelines set by the APA.

Over-prescription

A quick scan of the news portals nets a surprising deluge of sickening reports on the subject of over-prescribing. UK’s Channel 4 TV reported on concerns that antipsychotic drugs were being given out to children inappropriately, and with alarming frequency. In addition to the positive affects being questionable for many patients, these powerful drugs have nasty side effects. The major worry now is that pharmaceutical companies are actually blocking approaches to the authorities with data describing the long-term effects. Could this be a little bit of ‘cornered rat syndrome’ from Big Pharma? It’s common knowledge that many of the drug patents for the big blockbuster drugs are due to run out before 2013. It’s easy to see why connections between the APF, APIRE and the pharmaceutical industry are viewed so suspiciously.

The American Psychiatric Association want to list grief as a mental illness

Getting off Pharma’s treadmill

It’s time to ask ourselves some difficult questions if we’re to halt the doling out of prescription drugs for mental disorders. Disorders that should be more accurately recognised as normal emotional reactions to life-events.

The fact that emotional reactions often escalate to crippling conditions is more a reflection on the lack of community and social support, than a deficiency syndrome of pharmaceutical drugs. Has society become so time-challenged, so uncaring and so self-centred, that we are no longer capable of looking out for those amongst us? In many inner city areas, gone are the days when neighbours even know each other’s names or rally round in a crisis.

In our busy modern existences, many of the traditional support systems like social clubs, the Church or community hall, seem to have fallen by the wayside. Life moves on, technology continues to develop, but people are spending more and more time chasing their tales just to eek an existence and feed their families. For so many, it’s hardly what could be described as a high quality or meaningful life. Friends, family, neighbours, all used to rally round in life crises, but too many now find themselves alone and isolated at a time of crisis. With no one to turn to, they are often seen as dysfunctional and abandoned to the medical system. It’s very interesting that in indigenous communities unscathed by today’s corporatocracy, where that support system is very much in evidence, depression and anxiety disorders are quite rare.

The importance of community

Could it be that a very big part of what is missing in modern Western society is the chance of being seen, listened to and cared for — as a unique individual, with unique life experience, and unique problems? It’s no surprise that ‘support-centered’ groups such as Weight Watchers or Alcoholics Anonymous are so successful and when questioned, subscribers say a lot is down to feeling part of a community again.

Most of us have become aware that new-to-nature drugs cannot provide the answer to what ails us emotionally. Drug prescription is a concept that has been thrust on us by a wayward medical (healthcare?) system that has lost touch with the complexities of human beings, as sophisticated social animals.

We can either chose to succumb and be part of it — or we can chose to handle our problems differently — engaging our families, our friends and our communities. Never has there been a time when the “act local, think global” slogan, the catch-cry of social, environmental and justice campaigners, has been more relevant.

What can you do today to re-engage with your local community?

Comments

your voice counts

02 March 2012 at 9:19 pm

I could not agree more. It's all bullsh.t and it's all about money. These drugs are killing people in more ways than one. My sister died as a result of them 3 years ago at the age of 48. She dropped dead in her tracks of a massive coronary after being to the emergency dept 3 times all in the same day. She knew something was wrong and she was not treated (stigma). She was labelled paranoid schizophrenic 31 years ago, when she actually suffered a head injury and she was on these drugs all her life. More recently my husband of 30 years was labelled 2 years ago with depression. I didn't even know it and I live with the man. We were happily married until he was labelled. He has been on 12 different drugs and they're still looking for the right one. Even the psychriatrist said you're a guinea pig. I am very concerned for his health. What I don't get is how I live with the man and not know he has depression. The drugs don't help at all in my opinion they have changed him and the side effects have been terrible. I am really afraid sometimes that they will kill him. The doctors don't live with him I do.

Even me I was labelled 26 years ago as bipolar for 1 incident, I have been on medication half my life. The very first set of drugs they put me on almost killed me (serotonin syndrome) but fortunately I was in the hospital at the time and they were able to save my life. I am on an antiepileptic/epival. These drugs take a toll on your body, recently I was blind in both eyes and had implants put in at the age of 49. The doctors didn't know the cause, I have since learned it is my medication. Time will tell the long term side effects of these drugs, I have heard that they cut your lifespan by 20 years I guess that's a good case scenario if they don't kill you first.

Sincerely

Smiley

01 May 2012 at 7:12 pm

Emotional problems can be dealt with in 12-step groups. There used to be many in London in the 1990s. I think it would be a good idea to revive groups such as Codependents and Emotions Anomymous.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences