Content Sections

By Meleni Aldridge

Executive Coordinator

I've had the pleasure this week of spending three extremely valuable, information-dense days at the Institute for Functional Medicine’s (IFM) Annual International Conference (AIC). It's my 10th consecutive annual visit to the AIC, and Rob Verkerk's, 11th — these conferences representing an important part of our continuing professional development. This year the setting was Austin, Texas, and the theme was the role of genomics in healthcare.

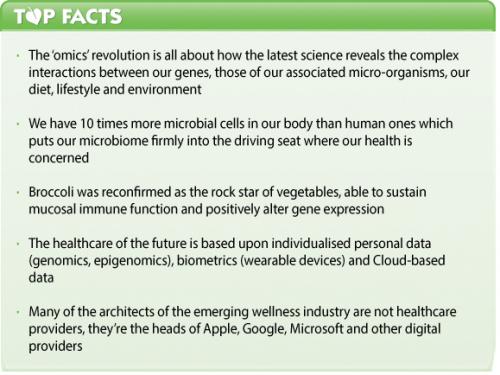

With the huge escalation of 'omics' science, the subject area is huge, but at the same time there is so much more to be learned. As usual, the IFM found a way of making some of the latest and most important findings clinically relevant. Despite the intense research focus since the Human Genome was unravelled in 2003, science is still barely scratching the surface of what there is to know. But this emerging knowledge has the potential to dramatically shape the healthcare of the future.

The AIC programme wound its way expertly through the world of ‘omics’ and the quality of the presentations was, as always from IFM, outstanding. However, if I had to distil the multitude of take home messages into just one word, it would probably have to be ‘broccoli’. This seemingly humble vegetable is actually one of the great rock stars of the phytonutrient world, capable not only of sustaining intestinal immune function, but its compounds are among some of the most powerful nutritional factors affecting gene expression. To its credit, it was feted and celebrated throughout the AIC by many of the expert clinicians who had prepared their presentations without prior knowledge of anyone else’s. It’s definitely time to devote an entire ANH-Intl article to the humble broccoli and its cruciferous siblings, also the focus of years of Rob Verkerk's research at Imperial College London. Happily, it’s also my favourite vegetable family. But given my personal array of genetic polymorphisms adversely affecting my methylation and detoxification pathways, could it be my microbiome driving my love of broccoli and all things cruciferous?

The ‘omics’ revolution

Functional medicine has always acknowledged that our health is dependent on the complex, continuous interactions between our genes, our lifestyle and the environmental influences around us. Science, in recent years, has uncovered a whole new world of ‘omics’. Healthcare is in the midst of an ‘omics revolution’ as a result. From genomics and epigenomics, through to proteomics, metabolomics, transcriptomics and beyond, the complex influences on gene expression are many and varied.

This year’s AIC brought together leading luminaries in the field to not only discuss the emerging knowledge base, but also to share important clinical applications now available. A snapshot of the hottest topics presented and distinguished speakers include:

- The recent history and current state of genomic science from Helen Messier, MD, PhD; Jeannette McCarthy, MPH, PhD; and Rachel Tyndale, PhD

- Professor Jeremy Nicholson, PhD helped envision how the future of medicine can be altered by breakthroughs such as genomics

- Genomic testing and how it is helping to change the way in which practitioners and clinicians approach diseases as diverse as breast cancer (Edward Staren, MD, PhD), heart disease (Mark Houston, MD) and common mental disorders (Jay Lombard, DO; Raymond Lorenz, PharmD; Robert Hedaya, MD)

- The critical role of methylation (Paul Anderson, ND; Myrto Ashe, MD; Kathleen Toups, MD, DFAPA), the vital importance of detoxification (Robert Rountree, MD), and the essential functions of the microbiome (Michael Ash, DO, ND) in patterns of gene expression was discussed at length through presentations and breakout sessions

- Direct-to-consumer genomic testing such as 23andMe and others — one of the hottest topics of the conference — was brought to life by Yousef Elyaman, MD.

Genetic origami

Jeffrey Bland PhD’s keynote lecture on day one brought to life the “match made in heaven” between functional medicine and the ‘omics’ revolution. He used Dr John Rinn’s recent quote in the New York Times to illustrate how our RNA molecules are pulling off genomic feats every day that allow life to occur as we know it. According to Rinn, “It is genomic origami. In every cell, you have the same piece of paper. How you fold that paper determines if you get a paper airplane or a duck. It’s the shape that you fold it into that matters. This has to be the 3D code of biology”. The piece of paper is our genetic inheritance, but how the ‘paper is folded’ is dictated by our nutrition, lifestyle and environment — and our microbiome (gut bacteria and other symbiotic microorganisms).

A healthy adult gut harbours a complex community of around 100 trillion microbial cells, referred to as the gut microbiome. That’s about 10 times the number of human cells we have in our bodies. That also means that we have 10 times the amount of non-human genetic material than we do human DNA, begging the question, who exactly are we? These gut microorganisms use plant compounds that we’ve consumed to regulate a wide range of critical functions (transcriptomics) including our appetites, our immune systems, our brain function and the way we store and use energy. They also have a lot more to say about what drives our needs and desires i.e. what we eat, our relationships and our social interactions, than we give them credit for. Even our energy generating organelles within cells, the mitochondria, have evolved from bacteria and still contain genetic remnants.

Dr Bob Rountree, this year's Linus Pauling prize winner, described humans as mobile warm-blooded coral reefs, home to vast numbers of microbial ecosystems that are rich in biodiversity. He referred to the ‘gene swap party’ that's continuously going on in our gut as our microbial friends are dynamically affected, as are our genes, by our diet, lifestyle and environment. Understanding and making use of the emerging science on the human genome is largely useless without also understanding the extensive role that our microbiome plays in our life. Hence the number of presentations devoted to gut immunology, the microbiome and even faecal transplantation in this year’s AIC.

Gene talk

It’s vitally important to understand that the plant and animal foods and herbs to which we’re exposed over our lives alter our pattern of gene expression (through proteomics, transcriptomics, metabolomics), and hence our phenotype and health status. This process is referred to as epigenetics or epigenomics. In essence, it’s about how our environment, especially our diet and lifestyle, shapes the way our genetic code is expressed. This includes the fact that these epigenetic changes create permanent alterations to our DNA (via processes called DNA methylation and histone modification) that can then be passed on to future generations.

These are among the many reasons why it’s so important to make sure you consume a diverse, nutrient-dense, plant-based diet with additional herbs, spices and phytochemicals. It’s not just your genes at stake, but also the diversity and health of your microbiome. As Michael Ash DO reminded us, “investing energy in the selection of the foods you eat has a much bigger effect on microbial composition than focussing only on your genes”. He presented research showing that dietary changes could explain 57% of the total structural variation in the gut microbiota, whereas changes in genetics accounted for no more than 12%. Again, demonstrating that if our first genome is our human genetic code, our second is the genetic code of our microbial partners, which appears to be a far stronger driver of health or disease. To complicate the picture further, there is a third genome emerging – that of our viral symbiotic partners, of which we still know precious little.

However, the field of epigenetics is giving us a much more nuanced and complex view of the interplay between genes and the environment. Not only in that multiple genes need to be taken account of in explaining conditions and behaviours, but that genes are in a sense tuned by the environment itself (microbes, foods, lifestyle, environment). Much of the turning ‘on or off’ of genes can be explained as a form of genetic memory, as if the experiences of our close ancestors, the food they ate and their survival challenges are encoded in the genes of their descendants — us.

Translational nutrigenomics

So when the rubber meets the road, our health depends on our ability to positively affect our nutrigenetics with our nutrigenomic interactions. Nutrigenetics speaks to the influence of gene variants (our genome and polymorphisms) on our ability to interact with bioactive molecules in the molecular environment surrounding our cells and the consequences of that interaction. Nutrigenomics on the other hand, is concerned with the impact of nutrients and bioactive food components on gene expression. Either through up regulating or down regulating (turning up or down), or activating or silencing (on or off).

For example, take our rock star broccoli that contains a powerful group of compounds called sulforaphanes. Sulforaphanes are able to induce a transcription factor that activates cellular defences through cell-protective genes. On the other side of the coin, harmful polyaromatic hydrocarbons produced through BBQ’ing (blackening) meat upregulate (stimulate) the expression of our first phase detoxification genes, which then create a lot of toxic secondary products, some of which are carcinogenic. The type of gene variants (single nucleotide polymorphisms or SNPs) a person has will determine their nutrigenetic response to these nutrigenomic influences.

Yael Shapiro PhD reminded us that our genome contains the information for making the proteins needed to run the body. Our epigenome refers to the chemical modifications to DNA and its associated histone proteins, whereas epigenetics involves changes to DNA that alter gene expression without altering the DNA sequence itself. Disruption of any one of these processes can lead to the inappropriate expression or silencing of genes, often leading to disease.

If epigenetics acts like a dimmer switch, then advances in epigenomic and genomic research are now making it possible to recommend specific dietary interventions aimed at modifying gene expression to optimise health and reduce disease risk. Enter personalised nutrition and ‘Culinary Genomics’ — the latter being the term coined by Yael Shapiro and Amanda Archibald in their inspirational presentation entitled Translational Nutrigenomics. Amanda Archibald RD has described culinary genomics as “the culinary integration of nutrient and bioactive-gene interactions, onto a nutrient-dense and diverse whole food canvas”. Basically describing the individualised nutritional protocol that “bridges the synaptic gap between the practice and the plate for the patient”. It's an area we will undoubtedly be seeing a lot more of in the future, as more and more nutritional practitioners shift towards prescribing individualised, 'food first' programmes for their clients and patients.

The healthcare horizon

The dawn of a new era of healthcare based upon the application of ‘omics’ within a systems biology framework is now upon us. Understanding the antecedents, triggers and mediators of disease in an individual, as well as finding ways of preventing disease, are central to the functional/integrative medicine approach which is set to gain massively from the omics revolution.

The quantification of wellness is a burgeoning new growth industry in healthcare as biometric data is collected and analysed automatically in real time through apps and digital wearables. People are becoming ‘activated patients’ through the information gathered in this way about how their lives and genes interact to influence their health. Using the wide rane of functional and genomic testing now available, organ-specific immunological assessment and personalised therapy is the major focus of this new medicine/healthcare. We will also be seeing the pharmaceutical industry developing drugs that modulate genetic expression and network biology, rather than just being agents that inhibit pathological (disease) processes without addressing the causes.

Information is power. The people sitting round the tables discussing the healthcare of the future are no longer doctors, health insurance providers or hospital administrators, they’re the heads of the likes of Apple, Google and Microsoft. The age of digital wearables (biometrics) and informatics (simple systems analysis) is here and healthcare is now all about consumer-driven active information. Clinicians and researchers need this information uploaded to the Cloud so it can be measured, understood and used to develop new strategies to support health. Wellness is the top drawer in the information pyramid right now.

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences