Content Sections

- ● Meat eating and the environment

- ● Production of different meats yield very different emissions

- ● Meat production emissions in terms of agricultural land area

- ● Meat production – the emission impacts of import and export

- ● Carbon capture in agricultural soil: the other side of the emissions coin

- ● But isn’t meat dangerous to eat?

- ● The Great Gates GBD fiasco

- ● Is Gates’ GBD mortally wounded?

- ● Snapshot of GBD 2019

- ● Gates' investments in land and fake meat

- ● The bottom line

By Rob Verkerk PhD, executive & scientific director

THE TOPLINE

- Red meat eating has been demonised because of its alleged adverse impacts on the environment and on health

- Find out why it isn't red meat that's the problem: it's the production system that's at fault, and why regenerative grazing that's adapted to local conditions is the answer

- Did you know that, gram for gram, wheat and rice production yield much higher greenhouse gas emissions than lamb, goat or buffalo. Industrial beef farming is a problem however you look at it

- The mainstream narrative pushes us to be concerned about greenhouse gas emissions, but fails to tell us how agricultural soils can readily be converted into incredibly effective carbon sinks

- A letter just published two weeks ago in The Lancet has exposed the flawed methodologies used in the Gates-funded Global Burden of Disease (GBD) project that wrongly suggests red meat is inherently harmful and any amount consumed will contribute to disease

- A further look at the GBD 2019 data has numerous anomalous findings that show the data isn't worth the Gates money it was funded with. Check out and please share our downloadable infographic

- Most of the findings appear to be linked to pushing agendas that fit perfectly with a business-with-disease model that is heavily fuelled by Gates Foundation funding.'

Any red meat eaters among you will be aware that it’s becoming ever more un-politically correct to do what your hunter-gatherer ancestors appear to have done food-wise to help all of us see the light of day. The driver behind this change in perception is less to do with ethics – as little has changed other than increased adoption of inhumane factory farming of animals. It’s more to do with the accumulating body of evidence that points to the environmental and health harms associated with meat eating, especially red meat, and even more especially beef eating.

Of course we don’t hunt with a spear any longer. Most meat in industrialised countries is industrially produced in factory farms. Much of the feed for these animals is genetically modified and has been imported over vast distances. Any review of the totality of available evidence suggests this kind of meat production is bad for the environment, contributing significantly to greenhouse gas emissions. It’s also ethically suspect given there are much kinder ways of raising animals, and the bit that many are focused on now is: it’s bad for health.

In this article we’re going to shed some light on where we are on both the environmental and health aspects of red meat eating.

Meat eating and the environment

Let’s start by trying to break down some of the complexities. A study taking in data from 200 countries published in Nature Food back in September, funded in part by the US Department of Energy, suggested that animal-based food (including livestock feed, transport, etc) contributed to a staggering 57% of global greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Plant-based foods, by comparison, contributed just half this amount (29%).

The ‘meat & dairy cause twice as many emissions’ story from this paper went global. Here it is in the UK’s Independent, Scientific American and the Vegetarian Times.

A nail in the coffin for meat, surely?

Production of different meats yield very different emissions

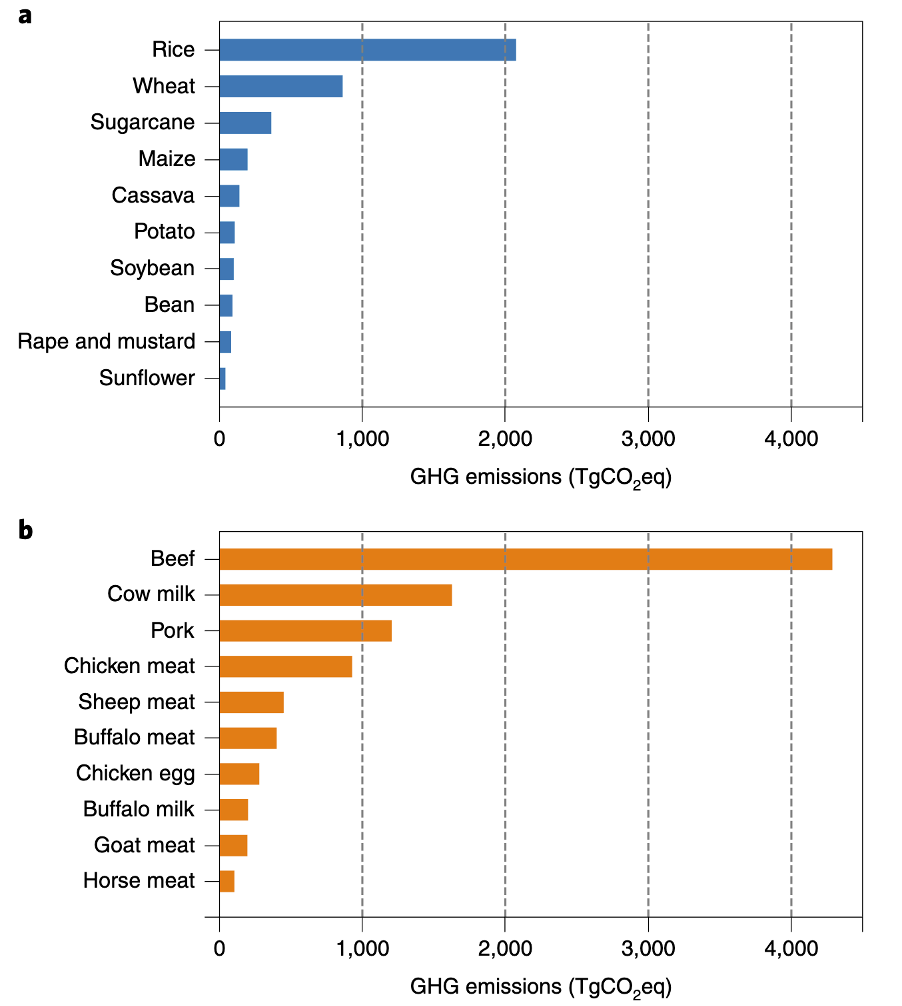

When you look deeper into the very same study, you see staggering differences in carbon dioxide emissions per gram of different meats, with some red meats contributing less than some plant foods.

For example, the mainstream-approved study relying on the production of both rice and wheat, the two most common staples, emit more greenhouse gases than sheep meat (sometimes also referred to as mutton and lamb), as well as goat or buffalo meat (see Fig. 1).

This alone means that saying meat, or even just red meat, results in more greenhouse gases than plant foods, is a non sequitur. In plain English, it’s a falsity or a lie. The data also tell us it is irrational to lump all red meat into the same category if you’re looking at trying to reduce environmental impact. Beef and sheep are like apples and oranges. As are rice and maize – again, why lump them together, unless there’s another agenda?

Figure 1. Global GHG emissions from (a) top 10 plant- and (b) animal-based food commodities. Source: Xu et al, 2021.

Meat production emissions in terms of agricultural land area

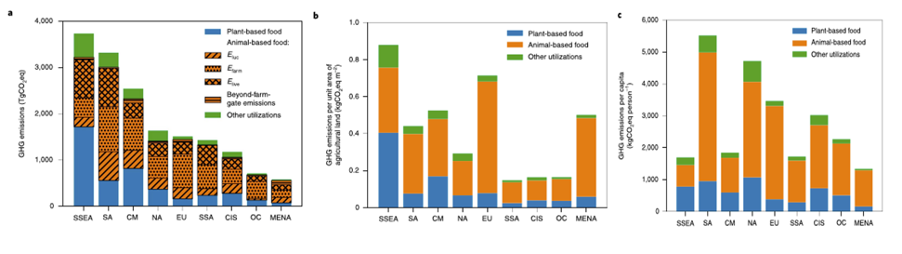

When you look at emissions per unit area of agricultural land, things look pretty disastrous for meat production in areas like the EU and the Middle East (Fig. 2). But they don’t in South and Southeast Asia. What does that tell you? It’s not meat production itself that’s the problem, it’s the production system for animal-based foods that’s a problem in some parts of the world. And not in others. Blame the production system, not the animal.

Of course that’s got a lot to do with if the animals are raised on industrialised farming systems with imported grain, as you can see (Fig 2).

Figure 2. Global GHG emissions of plant- and animal-based foods from (a) 9 different regions of the world (b) per unit area of agricultural land and (c) per capita. Where NA = North America; SA = South America; EU = European Union; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; CIS = Commonwealth of Independent States; CM = China and Mongolia; SSEA = South and Southeast Asia, and; OC = Oceania and other East Asia. Source: Xu et al, 2021.

Meat production – the emission impacts of import and export

You also see huge GHG contributions from import or export of feed for animal-based food (Fig. 3). Things look particularly bad for Europe that has little grazing land by comparison with North America, which, comes off rather well, comparatively (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. GHG emissions due to import and export of plant- and animal-based food in different regions. Where NA = North America; SA = South America; EU = European Union; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SSA = Sub-Saharan Africa; CIS = Commonwealth of Independent States; CM = China and Mongolia; SSEA = South and Southeast Asia, and; OC = Oceania and other East Asia. Source: Xu et al, 2021.

So far, we can conclude that placing different meats, even red meats, in the same category, while ignoring the massive differences in production systems in different parts of the world means you can’t see the wood for the trees. That means not being able to prioritise changes in production system or land use that make the biggest difference to emissions, especially when we must recognise that meat eating is very strongly correlated with improvements in standards of living. Contrary to what we’re often led to believe, population-based studies using United nations data also show increased meat eating is correlated with improved life expectancies.

But the over-simplification and incorrect rationale that continues to stigmatise meat-eating doesn’t stop there. If you only focus on emissions and ignore the ability of healthy, organic matter-laden agricultural soils to act as carbon sinks (referred to as carbon sequestration), you miss the other half or more of what is a highly complex picture.

Carbon capture in agricultural soil: the other side of the emissions coin

Low intensity, natural grazing systems can present an incredibly important answer. Zimbabwean biologist Allan Savory has long argued that ‘holistic planned grazing’ can be one of the best ways of converting marginal land into carbon capture systems.

But regenerative grazing has caught on all over the world, even in the UK, where it has been shown to yield higher output because it works in harmony with natural cycles.

Planting crops on the more marginal lands suitable for grazing, especially if they’re monocultured and dependent on high fertilizer, herbicide and pesticide inputs, does the exact opposite; it kills microbes in the soil and prevents soils from developing the rich organic matter and microbial contents that can so effectively absorb carbon from the atmosphere.

This means that lower intensity animal farming systems, as are common in places like the UK, make a much smaller contribution to emissions – and act as more effective carbon sinks – compared with the global average.

The National Farmers Union (NFU) argues UK beef production causes only 40% of the emissions compared with the global beef production average, and so shouldn’t be pushed into decline by stigmatising it. Instead, says Minette Batters, NFU President, British farming can achieve net zero emissions by 2040 by becoming more efficient, capturing more carbon in the soil and in plants, and displacing more carbon emissions. This is all part of the NFU’s ambitious but still realistic Achieving Net Zero plan. Improved carbon capture is proposed through bigger hedgerows, more trees, enhancing soil organic matter and conserving carbon stores in grassland and pasture.

But isn’t meat dangerous to eat?

Having set the scene for why red meat itself isn’t necessarily bad for the environment if animals are raised on sustainable production systems, you still might think it’s best avoided on health grounds, if not environmental ones.

This is where most roads lead to The Lancet, the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funded Global Burden of Disease studies, and the EAT-Lancet Commission that reported its findings back in January 2019. You’ve got it: it’s pretty much a Gates/Lancet affair.

By the time covid-19 emerged as a dominant theme in so many of our lives, the mainstream opinion was that meat was pretty dangerous all round: for the environment, and for health. The EAT-Lancet Commission was a key element in bringing the public mindset to this viewpoint – and we issued a 25-page rebuttal to the 47-page Lancet-published output shortly after it was issued in January 2019 to a fanfare of publicity. So we won’t say more on it here other than the EAT-Lancet report was deeply flawed (extensive reasons being given in our rebuttal).

The Great Gates GBD fiasco

The view that red meat is inherently harmful was perpetuated by findings from the latest (2019) update of the Gates funded Global Burden of Disease study. Among the study’s findings was that the theoretical minimum risk exposure level (TMREL) for red meat should be changed from 22.5 grams per day (set in 2010) to 0 grams per day.

This dramatic change implies that red meat is inherently harmful, and the more you eat, the greater your risk of diseases that can kill you, like heart disease, cancer, or diabetes. The trouble is, this kind of dose-response is not supported by a wide range of other data from the real world, including another global study released in September 2021 focusing specifically on unprocessed and processed meat, namely a new analysis of the global PURE (Prospective Urban Rural Epidemiology cohort). Or you might want to look at another global epidemiological study, relying on United Nations data, that found that meat intake across 175 countries or territories was positively correlated with increased life expectancy.

Is Gates’ GBD mortally wounded?

Fast forward to a couple of weeks ago when a very damning letter, published – in The Lancet, by six scientists challenged the methodologies and findings from the GBD 2019 study. The team of six was led by Prof Alice Stanton from the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland.

Stanton et al slam the scientific basis on which the GBD 2019 study claimed that the death rate attributable to red meat was 36 times greater than that found just two years before, in the GBD 2017 report. A rise of such magnitude surely cannot be due to a biological response, whether from production systems or the human health response to a particular food type?

The authors of the GBD 2019 study acknowledge changes in metrics and data sources, suggesting the data they had for the 2019 analysis was better in quality than those for 2017. It all sounds plausible, until you look at the manipulation, once again, undertaken courtesy of funding by Gates.

Among the scientific travesties that led the Gates-funded GBD 2019 collaborators to demonise red meat were:

- Without anything like enough data, but presumably with no shortage of belief, the authors assumed red meat consumption and ischaemic heart disease, breast cancer, haemorrhagic stroke, and ischaemic stroke had now become causally associated.

- Insufficient data were made available by the GBD 2019 collaborators to independently evaluate the conclusion that the risk of stroke was greater for those consuming only modest amounts of red meat daily (50 grams) compared with those consuming none. Why weren’t the raw data made available given the need for transparency?

- Stanton and colleagues slam the GBD authors for flouting the required best practice guidelines required by The Lancet and all leading medical and scientific journals, notably, for global health estimates, Guidelines for Accurate and Transparent Health Estimates Reporting (GATHER) and PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines, for systematic reviews and meta-analyses. This disregard for guidelines that are intended to ensure high quality science should have been sufficient to reject the study – or if discovered retrospectively – have the paper retracted. Sadly, we’re more likely to see governments building policy on faulty data, and Gates continuing his ‘plant-based/artificial meat’ global take-over. Did I hear you ask: when did a Gates funded study last get rejected? We're not aware of any. It seems when you control people with your money you can get away with a lot that others can’t.

>>> For a detailed analysis of where GBD 2019 went wrong – see an illuminating exposé by friend and colleague, Zoë Harcombe PhD issued on 7 March 2022

Snapshot of GBD 2019

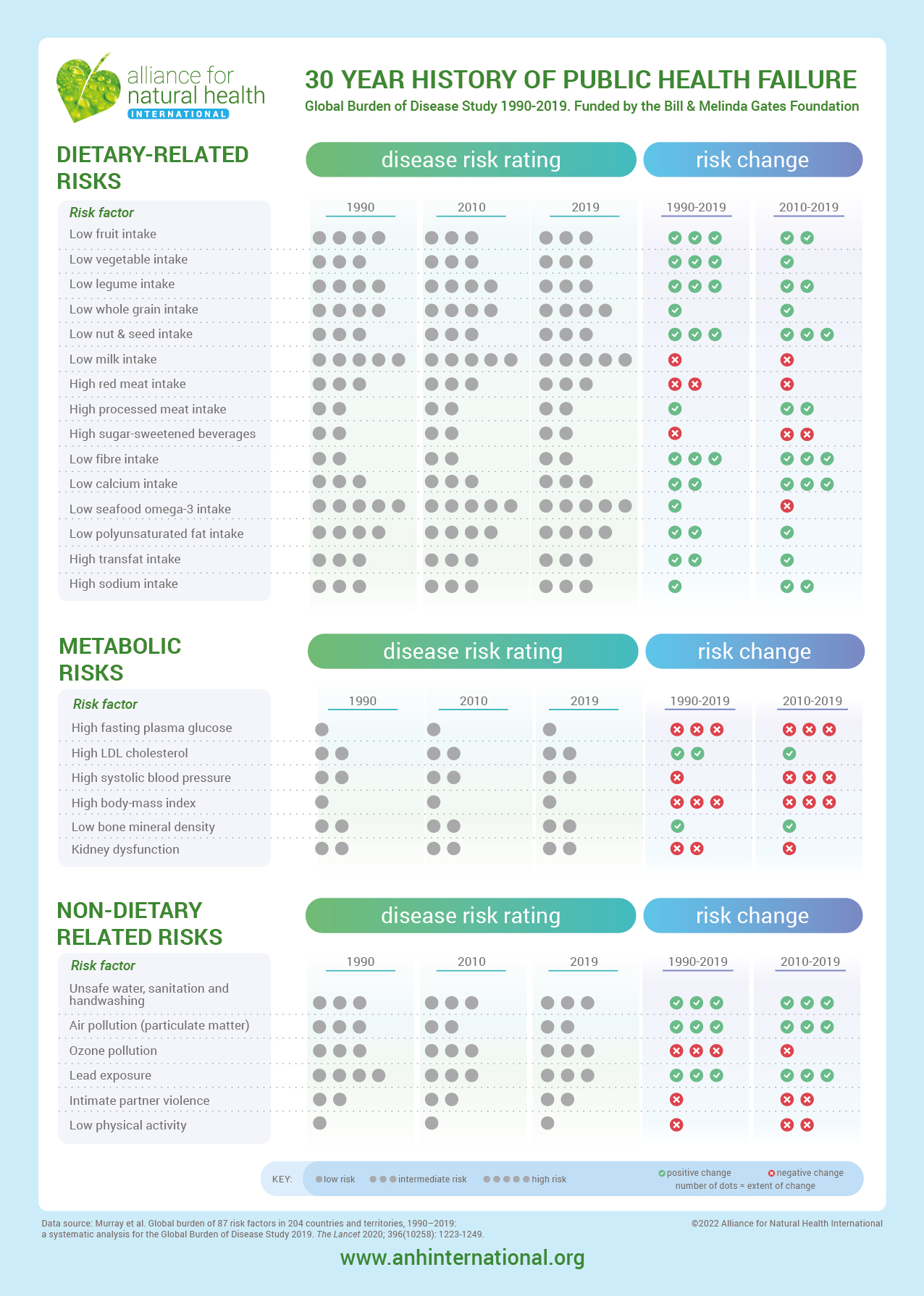

Alice Stanton’s letter to The Lancet caused us to look again at the GBD study.

What you can notice within it is a whole gamut of inconsistencies that are strongly suggestive of either the underlying data or the methods of analysis being faulty. Or both. We’ve taken key parts of the section that deals with risks and compiled them into an infographic (Fig. 5).

>>> Click here to download infographic as a sharable, printable PDF

We’ll largely let the infographic speak for itself, other than drawing to your attention some of the big inconsistencies that remind us we wouldn't want public health policy – or individual’s self-care decisions – being overly influenced by GBD studies.

Let’s take a few eye-watering examples:

- One of the biggest risks of chronic disease globally appears to be a low cow’s milk intake. That’s very odd when cow’s produce milk for calves, not humans. Cow’s milk is not an essential food, and it is a foodstuff to which vast numbers of people demonstrate intolerance or allergy. You can see also in the right hand two columns, the risk of disease over the last 30 and even the last 10 years hasn’t improved a great deal – suggesting we should all be pushing more people to drink more milk. What? And suffer more intolerance, leaky gut, digestive, immune and other issues?

- What about physical activity. It turns out – if you want to follow the recommendations of the GBD collaborators – you’re wasting your time being active. You might develop a high body mass index (i.e. become obese) but that’s not a big risk factor either, it seems. Then go sit yourself on the couch and grab the TV remote – it won’t make much of a difference either way. If you then want to open a few cans of your favourite 'sugar-sweetened beverage', that’s OK too – it only represents a relatively low risk to you – so if it makes you happy, go for it.

- Now, please, dive into your nearest fast food diner and get those polyunsaturated fats into you – even the highly processed seed oils (GBD doesn’t distinguish food quality within major food categories). But wait, one of the biggest risks out there is a shortage of omega-3 oils from seafood; yes – maybe this time they’re right – but what are we going to make of that when we can’t trust so much of the other data?

- Something of a success story apparent in the data (still on the infographic) seems to be the reduction of high LDL cholesterol which it appears is not as dangerous as we’ve been led to believe. But the trend at least has gone in the right direction – no doubt because of aggressive campaigns by doctors to push statins on the over-50s.

- But hey, people are still managing to become heavier (and presumably fatter) over time, as shown by the negative trends in body mass index (BMI) over the last 30 and 10 years, respectively.

Another of many public health failures, yet highly profitable for those selling us their wares.

Any rational scientist looking at the GBD findings, like Alice Stanton, would say there’s something amiss with the data, or its analysis. How come so much of it is inconsistent with empirical or observational studies in the real world, and points in the direction of benefiting some of the most powerful individuals and corporations on the planet?

The sort of things we're talking about include: monoculture grains cultivated with the aid of huge quantities of the world’s number one agrochemical input, glyphosate; artificial (cell-based) meat; sugar-sweetened fizzy drinks or sodas; dairy; and of course statins.

Junk science supports junk food which delivers junk health. All on Gates money.

Gates' investments in land and fake meat

-

Gates is the largest farm owner in the USA

-

Gates has invested in a fungus-based fake meat alternative: Nature's Fynd

-

Gates tells rich countries to eat synthetic beef (from which he benefits)

-

Gates' sell-off of Beyond Meat shows he's about money not mission

-

One of Gates' investments in lab-grown meat: Memphis Meats

The bottom line

With no further ado, let me conclude as follows:

- An abundance of evidence shows that meat production isn’t inherently bad for the environment. It depends on how and where you raise your animals, and it’s different for different animals raised in different places

- An abundance of evidence also shows that meat – even red meat – isn’t inherently harmful to health. But certain types of meat, produced from certain production systems, eaten as a part of certain (unhealthy) dietary patterns – are clearly bad for health

- There is no evidence that demonising meat and encouraging an ever larger number of people on the planet to avoid eating meat or consuming dairy will resolve environmental or health problems

- There is no available evidence that cell-based or other artificial meat technologies will be as good for health as modest amounts of meat from regenerative grazing systems

- High input, intensive agriculture that relies on plant crop monocultures is inherently harmful to the environment, reduces biodiversity, damages soil, reduces organic matter content and carbon sequestration capacity, and yields food quality that is inferior to that cultivated through regenerative agricultural practices

- Eating locally or regionally produced foods that don’t involve long-distance importation of commodities, as well as consuming diverse and varied diets, appear to be the healthiest dietary patterns for everyone (see more about our book RESET EATING below)

- To help remedy unnecessary damage to the environment, as well as to be able to reduce unnecessary GHG emissions, we must more effectively identify those regions in the world where highly intensive agricultural production systems will lead to environmental damage and loss of biodiversity, and which areas can be more tolerant of sustainable intensification. This demands moving away from a one-size-fits all approach that suits the globalists.

Blanket agricultural recommendations are about as useful as blanket public health recommendations: they both have spectacular histories of failure.

Finally, when you do see globalised efforts that attempt to push the population of the planet in one direction or another, follow the money. It won’t take you long to work out who the intended beneficiaries are. In the food and health arena – the sweet-spot of ANH – you’ll find that an increasing web of roads leads to one man: Bill Gates.

>>> To find out more about healthy, sustainable eating patterns – that help turn your food into powerful medicine - buy a pre-publication copy of our book RESET EATING that will be launched officially at the end of the month. *** 25% discount for ANH Pathfinders using code - Pathfinder25 - till midnight GMT 27th March 2022 ***

>>> Back to homepage

Proudly affiliated with: Enough Movement Coalition partner of: World Council for Health

Comments

your voice counts

26 March 2022 at 4:11 pm

Don't forget soil degradation and remind people in California that forest fires should totally be blamed on the state government -- they need to keep the land frequently watered and not throw rain water in to the ocean. Grass-fed meats are the best to eat but it also matters what the animals we eat eats. There should be a great, organic winterized animal food that is tasty, healthy and not filled with omega 6 flours like wheat, soy, corn and junk oils. Most of us are grain/gluten intolerant whether people know it or not.

26 March 2022 at 4:22 pm

I am also a member of the Center for Biological Diversity, and they are claiming that even well raised meat is bad for the environment. I have not read in length their arguments, but someone like you who has fully researched this issue should debate them!

27 March 2022 at 9:12 am

There's another "beef" regarding ranching: I have seen repeated evidence of a HUGE conflict between ranchers and wildlife. Most of the so-called "wilderness" parks I've been to in California, where I live, have huge fenced-in areas handed over to ranchers at low rates. These are in actuality mainly cow parks, and wildlife has little if any consideration there, while cattle overgraze to the point where little native vegetation survives. A great example is Point Reyes National Seashore, which was actually purchased from ranchers for a wilderness and THEN largely fenced off to keep the endangered Tule Elk OUT of most of the Cow Park. The elk have been DYING because they are unable to access the forage and water they need, and the idiots running the damned place have actually been SHOOTING them when the elk manage to escape the fenced area, in order to keep the park safer for the cattle. Looking outside California, bison in Yellowstone are killed if they attempt to migrate out of the park to reach their historical winter range and avoid starvation. Ranchers also join forces with hunters to reduce or eliminate the predator populations a healthy wilderness needs.

31 March 2022 at 10:14 pm

I use to spend my summers in the country, everyone shared their ponds for fishing and even land for grazing etc. and never witnessed the kind of man-said crisis before. Ridiculous does not even touch it. Cattle on the farms never stayed or stay in just one area for extremely long periods of time, they would be moved to another area for the time being and be moved as needed and would always come back to said area that they would have been previously moved from. It's called nature. Now if you throw in all the genetically modified crap they use now, it's all in concert with the plans of ridding the world of 99% people through just another manufactured, non base evidence for control and mass hysteria for the ones that have never explored outside a city or their bubble. Easiest ones to manipulate. They assume people will take businesses like National Geographic to give them the correct information. All bought and paid for. Thanks, Bill.

01 April 2023 at 6:56 am

There is a book worth reading for a balanced view. "On Eating Meat. the truth about its production and the ethics of eating it." by Matthew Evans. Murdoch Books. 2019. It gives you the science and the facts but does not favour any option. "compelling, illuminating, and often confronting." Yes indeed it is. Most informative and highly readable.

06 May 2023 at 1:06 pm

I'm a vegetarian who eats fish. I do this because I can kill a fish, but could never kill a cow or a pig, or a sheep or goat for that matter. This article is very informative, but glosses over the fact that the vast majority of supermarket meats come from unsustainable production systems. It's quite challenging to find meat that is grown sustainably, and virtually impossible to find mutton or goat. Not to mention the fact that most people have zero appreciation for the life given to bring that slab of dead thing onto their plate.

While I agree that Gates and lab-grown meat is a non-starter, this article seems to encourage people to eat meat with impunity, that people don't have to take responsibilty for where it comes from because it's the production system's fault. People need to stop eating meat to stop supporting that system. More importantly - and this is nowhere in the article - a culture change needs to take place so meat eaters can understand what it means to take a life and consume it. Our spear-carrying ancestors didn't eat meat most of the time, it was too dangerous to obtain and used up too many calories - they did it when there was no other food around. Hence our evolution into creatures who benefit from a small amount of animal protein, and can live optimally healthy lives without sacrificing land animals at all.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences