Content Sections

Fighting for our rights: 1215 to 1776

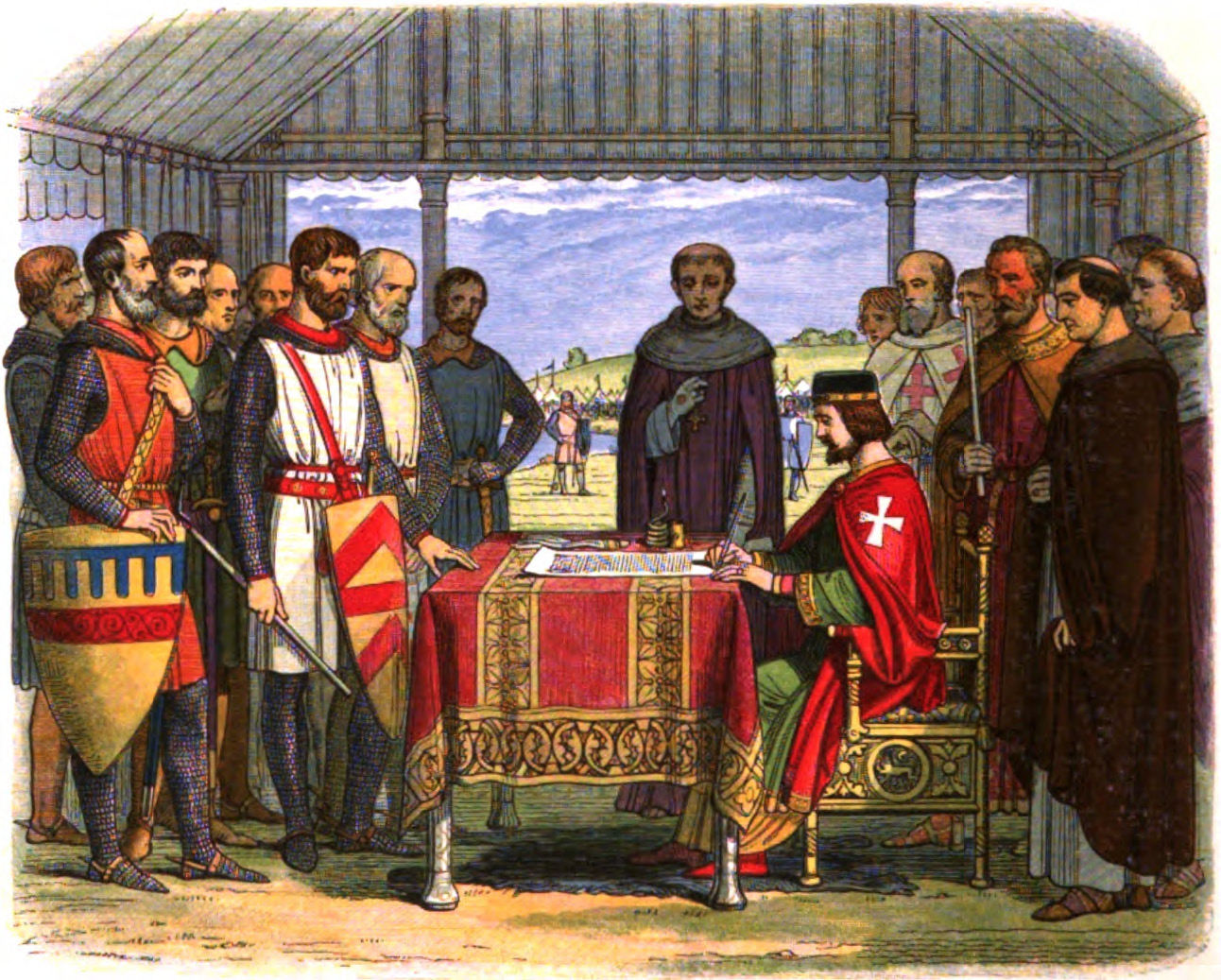

As 2015 opens, and we publish our first eAlert of the year, we felt it important to remind ourselves that we have entered a centenary of the Magna Carta. It was 800 years ago this year (15 June 1215) that an embattled King John was compelled to seal the ‘Great Charter’ on the banks of the River Thames at Runnymede.

Symbolically, at least, The Magna Carta enshrined the fundamental rights of ordinary people and put no-one, not even a King, above the law. Clauses 1, 13 and 39 remain in statute in England today.

Depiction of King John sealing the Magna Carta at Runnymede, 15th June 1215

The Magna Carta was born out of a need to limit the powers of a monarch, an unelected individual who was able to act seemingly not in the interest of his subjects. It survived just 10 weeks because John pulled strings in Rome and had the Pope annul it on his behalf. It was a conspiracy of sorts. The Charter was re-issued with revisions in 1216, 1217 and then 1225, under the guidance of the Archbishop of Canterbury, Stephen Langton. It was fully supported and then signed by Henry III, John’s son, who inherited the throne aged 9 after John’s death in 1216.

The Magna Carta is possibly the first constitutional document that enshrines the principle of the rule of law that is now the foundation stone of the constitution of most democratic societies. Some argue the document is so important, it is England’s ‘greatest export’.

Nearly 500 years later, the Bill of Rights 1689 secured parliamentary supremacy over the Monarch in England. It was the result of the so-called Glorious Revolution.

Across the pond, the Founding Fathers worked together to draw up and sign the Declaration of Independence in 1776. The United States of America was founded at this time by a unique group of people, led by George Washington, who valued particular principles about humankind, liberty and constitutional government.

In his first Bunker Hill oration in 1825, Daniel Webster said;

“We can win no laurels in a war for independence. Nor are there places for us ... [as] the founders of states. Our fathers have filled them. But there remains to us a great duty of defence and preservation, and there is opened to us, also, a noble pursuit, to which the spirit of the times strongly invites us. Our proper business is improvement.”

That’s worth pondering.

To the present

At a time when many are questioning whether their fundamental rights are being disregarded, including among those wishing to manage their health by natural means, we should perhaps remind ourselves of how those before us risked their lives and everything they owned to secure greater freedoms. Many of these we still enjoy today.

History tells us we can’t sit back and expect these rights to remain. The garden will overgrow with weeds if we stop weeding. Our rights are continuously threatened and must be continuously defended. In the West, the threats these days are rarely from monarchs. They now come more from ‘corporatised’ governments (most), unelected leaders of trading blocs (like the EU) and also from transnational corporations and trade agreements (like TIPPS).

The language used in the European Convention on Human Rights and the European constitution, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (also known as the Lisbon Treaty) is sometimes ambiguous. Some might argue deliberately so. It’s a cunning system; it gives with one hand and takes with another. But we shouldn’t forget it’s actually more or less the same system our ancestors before us lived with. And as Webster suggested, we should strive to improve on it.

The European charter and treaty documents refer directly or tangentially to most of our fundamental rights. For example, our right to self-determination, to liberty, to freedom of movement, to freedom of thought, to freedom of expression and speech, due process of law, freedom of religion, freedom of association and to peaceably assemble. But in the same stroke, they deny us these rights if their expression is deemed to threaten national security or public health. Interpretation of just what threatens public health, or national security for that matter, can be so broad as to effectively hand a loaded gun to the arbitrator, such as the international Courts of Justice or Human Rights in the EU.

Current challenges

Those of us committed to using non-pharmaceutical modalities as our primary means for maintaining health, face myriad of challenges in the EU.

Vitamins are a good example. This year, we may see an attempt by the EU to limit our intake of amounts of vitamins and minerals that are good for most of us by imposing unrealistic safety factors that apply almost entirely to imaginary individuals.

More and more herbal products are being classed as unlicensed drugs or unauthorised novel foods.

As of 2012, we’ve seen the implementation of provisions of the EU health claims regulation. These were nearly blocked with our help at the European level, but the ban on around 2,000 health claims that were in widespread use in the EU dramatically infringe freedom of commercial speech. The terms probiotic, prebiotic, antioxidant and superfood, to name a few, are now technically banned on commercial food or supplement products throughout the 28 Member States of the EU, containing half a billion people. This doesn’t just affect companies. It affects consumer choice, and in turn, consumer health. The big companies are wholeheartedly behind the regulations that are the brainchild of a consortium of corporate and government interests in the EU.

We cannot stand by and allow such infringements of our rights. We need to act together. We have been deeply involved in looking at ways in which we can work more effectively with more people to bring about change.

We are excited to do this and look forward to your support in 2015. Let’s remind ourselves of what the English barons did in 1215.

It’s our turn now. Let’s stand shoulder to shoulder — it’s our best chance.

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences