Content Sections

Described as the biggest health challenge of modern times, the number of dementia sufferers globally is on a steep upwards trajectory. With the number of sufferers predicted to soar to more than 150 million cases by 2050.

Traditionally viewed as a disease of the elderly, young-onset dementia is presenting new challenges and adding to the burden on existing health systems. Cognitive decline is not an inevitable consequence of ageing though. The links between our diets and lifestyles are becoming more and more apparent. The World Health Organization has recognised these risks in their new publication ‘Risk Reduction of Cognitive Decline and Dementia’.

Defining dementia

Talk about dementia and most people rightly think of Alzheimer’s disease. It accounts for around 80% of cases. But the term dementia goes broader and is used to describe a range of different conditions associated with a decline in brain function. A new form of dementia, termed Limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) that mimics Alzheimer’s, has recently been classified by researchers.

Currently dementia is considered to be incurable. It’s becoming painfully obvious we don’t understand what causes it despite millions being pumped into research. Researchers are flying blind as, one by one, theories, potential drug targets and drugs fall by the wayside. Pharmaceutical medicine works on the idea of establishing targets that are linked to the causes of the disease. But if you don’t know what’s causing the disease you can shoot drugs at specific targets all day long – but don’t expect ground-shattering results. Just one reason why successes with dementia and Alzheimer’s are proving to be ineffective.

Still widely ignored by mainstream medicine, cardiovascular disease and Alzheimer’s disease share a common risk factor. Namely increased levels of homocysteine due to inadequate intake of B vitamins. Whilst supplementing with B vitamins seems to provide a simple solution to combatting Alzheimer’s, once symptoms have developed it’s akin to shutting the stable door once the horse has bolted.

Read more about the link between B vitamins and brain health

Upstream, multiple causes – downstream diagnosis and management

Just as type 2 diabetes is known to be linked to inappropriate diets and lifestyles, Alzheimer’s is increasingly being associated with a complex of factors common to Western diets and lifestyles. One of the leading researchers in this field, Dr Dale Bredesen from UCLA has identified over 36 key contributory factors. His latest protocol – reCODE — that helps determine where someone is on their journey towards cognitive decline or Alzheimer’s involves generating data on around 150 different markers. Some of these are genetic (e.g. specific APOE4 alleles), others relate to dietary factors linked to consumption of too many processed carbs or sugars that in turn lead to insulin resistance. There are of course a host of environmental factors that have also been implicated, ranging from over-exposure to metals like aluminium or copper, or toxic moulds in the bathroom. But it soon gets complicated – and isn’t it so much easier to wait for someone to produce a magic bullet – that always seems somewhere around the corner?

The other challenge is by the time disease has well and truly manifested, it’s often too late to modify diets or lifestyles and reverse the disease. But as with type 2 diabetes, type 3 diabetes is potentially reversible – especially if ‘caught’ early enough.

Check out an interesting interview of Dr Dale Bredesen with Dr Rhonda Patrick on FoundMyFitness.

Medication of the masses with statins has also been linked to reductions in cognitive function.

As with so many of today’s chronic diseases focus needs to shift to upstream fire prevention rather than attempting to simply manage the flames of inflammation once alight.

Modern living harms

Ageing brings with it the expectation of developing some form of dementia. However, in the blue zones of the world, it’s a rare occurrence, despite these being long-lived societies. So, it’s not age that causes the disease. It’s what we do with our bodies during the earlier parts of our lives. What sets the blue-zoners apart from the rest of us? Again, there’s no one factor. Nine have been identified, including minimally unprocessed diets, regular physical activity, life purpose, close-knit communities and low levels of stress.

As more information is gathered on about the dementia puzzle, we’re seeing a continuing shifting of the goalposts, ones extending well beyond diet and lifestyle. Evidence is emerging of the dangers posed by chronic, daily exposure to environmental toxins in personal care products, air pollution and pesticides sprayed on our foods – these representing just a snapshot of the thousands of substances most of us are exposed to on a daily basis.

Counting the cost

The economic and social cost to society as a whole is massive given our current inability to prevent and treat dementia, adding as it does a whole new band of mental illness to the disease burden. Industrialised societies with a top-heavy ageing population are teetering on a catastrophic cliff-edge both in terms of cost and care. The burden on those societies with younger populations is currently less onerous. In the UK alone, the current cost burden of dementia is estimated to be £26bn, projected to rise to £59bn by 2050. That means the financial cost of type 3 diabetes is on par with that of type 2 diabetes. A scary thought.

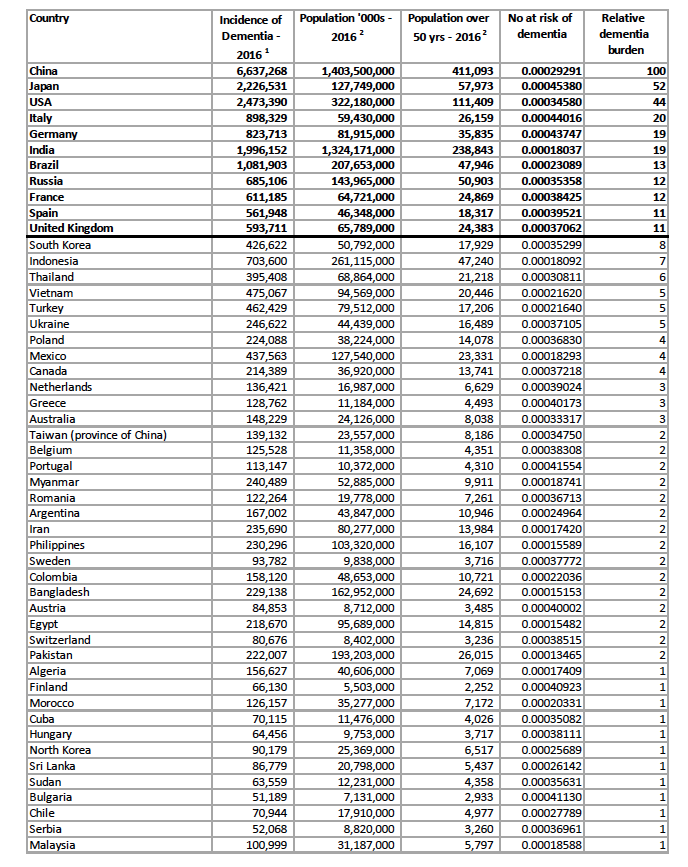

A recent Lancet study provided a detailed analysis of the global prevalence of dementia. Using these data along with population data, we created an estimate of the relative dementia burden on individual countries. This gives some idea of which countries will have the most work to do to offset the escalating problem, assuming nothing changes – and the future burden isn’t increased.

Table: Relative dementia burden by country based on 2016 data

1 United Nations, Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division (2017). World Population Prospects: The 2017 Revision, custom data acquired via website

2 Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016

As you’ll see, China’s burden is immense – and can’t be pointed directly to Western lifestyles. Japan is surprisingly high too, the problem being exacerbated by being among one of the countries with the longest national life span. The analysis also shows that India, even with its relatively bottom-heavy age structure, isn’t immune to the problem. What’s just as interesting is that some countries, like Switzerland, have long lifespans, yet have a surprisingly low burden compared with say the USA and neighbouring Italy or Germany. What’s really going on? The fact is we don’t have sufficient data to explain this with any degree of certainty.

Taking back control

Amid all this uncertainty of what is clearly a multi-factorial disease that takes decades to manifest, let’s get one thing straight: Dementia is not an inevitable part of ageing. Given that the seeds of Alzheimer’s disease are sown 20-30 years before symptoms appear, taking diet and lifestyle action early, while minimising exposure to neurological toxins and positively transforming stress in your life, in other words optimising your ‘health ecosystem’, both reduces your risk of dementia and provides you with a super-sized serving of other benefits to boot.

This means monitoring early – and routinely, say every 3 or 5 years, especially among the over-45s. Not necessarily all of Dr Bredesen’s 150 markers in reCODE, that will set back a US citizen a pretty $1,399. But there are many markers that are common to many of our modern diseases – many of which are being ignored by mainstream medicine because their testing can’t be converted to a drug prescription.

That’s built right into the approach outlined in our blueprint for health system sustainability, which puts each one of us in the driving seat of managing our own health.

Just to finish, you can live a longer, healthier life by following some simple points:

- Focus on whole, unprocessed fresh foods, limited carb-heavy, refined, sugary and processed foods to prevent metabolic dysfunction

- Eat a rainbow every day, incorporating as wide a diversity of plant foods to support good gut health and reduce inflammation. A good starting place is the ANH-Intl Food4Health guidelines

- Find your community. Research has shown those with active social lives have a lower risk of developing dementia

- Define your purpose, your reason for getting up in the morning

- Stay mentally alert and active. Activities such as reading and writing are linked to a slower rate of cognitive decline as we age

- Take the Food for the Brain cognitive function test and consider following Food for the Brain’s Plan B Positive Action on Alzheimer’s – which includes high dose B vitamins for those with elevated homocysteine and some degree of decline.

- Incorporate regular, daily exercise (at least 30 minutes) into your life

- Reduce your exposure to new-to-nature toxins – chemicals that your great grandparents never encountered.

As they say in Star Trek “live long and prosper”!

Comments

your voice counts

16 May 2019 at 10:22 am

Very interesting and confusing table. What to make of China, Japan, USA, Germany and India in the top. Is being a large country with a high GDP a risk factor? ;-)

I heard of two explanations for the Alzheimer epidemic:

- Low fat diets. The brain needs fat. But in that case it makes sense that the USA is in the top. Not India!

- Aluminium from pharmaceuticals and vaccines since aluminium is a proven neurotoxin. But in that case I would not expect Japan in the top.

And why is the dementia burden 10 times lower in the US than in Canada? Is the Canadian diet that much better?

The only thing I can maybe make of it is that countries that have a lot of work stress such as Japan, USA and also China seem to be high up in the list.

A mix of stress, diet and use of pharmaceuticals maybe?

Very confusing. I almost start to question the data. It would be very interesting to to come up with theories and test them against this bizarre mix of countries.

16 May 2019 at 6:26 pm

Excellent overview of Dementia globally; interesting that Italy - home of the Mediterranean diet - seems to have a far greater problem than the UK... what say you?

17 May 2019 at 9:47 am

And Ireland?

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences