Remember how the global response to Covid last March was all about stopping hospitals from being overrun? It turns out very few were ever overrun. Then there was this big focus on kids and young people, as it was thought children might be ‘superspreaders’ who would go on to ‘kill Granny’.

Kids misjudged as superspreaders

As early as June, the likes of Spanish paediatrician and public health specialist, Dr Luis Rajmil, showed how the available evidence at the time revealed that children could be no more important than adults as spreaders. It turns out, unsurprisingly, you can’t just transfer knowledge and experience from influenza and apply it to covid.

Then, in July, Swedish epidemiologist, Dr Jonas Ludvigsson from the Karolinska Institute, well and truly put the nail in the coffin of the idea that kids might be the problem, pointing to evidence that showed that is was unlikely that kids were the main driver of the pandemic.

Kids: from problem to solution?

Now we have a new insight. Kids are not only unlikely to be superspreaders, they could actually be a significant part of the solution. It seems their exposure to the virus may create one of the most effective ways of breaking transmission cycles of SARS-CoV-2. If that turns out to be the case, the Preston-born slogan “don’t kill Granny” will have been another policy that will need to be U-turned, like vitamin D.

The latest insight comes from a very detailed case study on a single family published by a group from the Murdoch Children's Research Institute and the University of Melbourne, led by Dr Shidan Tosif, just published in the journal Nature Communications.

The purpose of the study was to monitor in great detail the immune responses in one particular 5-person family in which the two parents (female, age 38; male, age 47) contracted the virus on a 3-day inter-state trip from their Melbourne home to attend a wedding. When they got home, they developed symptoms (fever, cough, runny nose, headaches, fatigue, headache) that lasted around 2 weeks.

Two out of the three kids (both boys, aged 9 and 7) developed mild symptoms but the youngest, a girl (aged 5), remained entirely asymptomatic. The symptoms in the older of the two boys were slightly worse than the younger boy, including cough, runny nose, sore throat, abdominal pain and loose stools. The younger boy suffered only a cough and runny nose. The girl remained entirely free of symptoms despite having the closest exposure to her parents when they were infectious, sharing the bed with them when they were unwell.

The Melbourne family that were subject to the detailed case study. The children all developed a SARS-CoV-2 immune response after chronic exposure to the SARS-CoV-2 virus from their parents but never tested positive. Source: Murdoch Childrens Research Institute / AAAS EurekAlert

Despite repeat PCR testing, none of the 3 children ever received a positive test result. Yet, despite having no evidence of replicating SARS-CoV-2 in them, all three kids developed strong antibody responses as measured in saliva and blood plasma. Additionally, the adults developed strong and sustained T-cell responses which would have conferred long-term immunity.

What’s particularly interesting is that the youngest child who never had symptoms developed the strongest antibody response and that response was especially strong in the saliva. The authors of the study rightly suggest that this could mean that children can develop a very strong innate mucosal response to virus particles that land in the nose, mouth and airways that prevents the virus from gaining entry to the body and replicating. Hence the lack of evidence of replicating virus in these three children.

What can we learn from the Aussie family?

It’s early days in terms of understanding a new disease, but let’s tease out a few key points that this study brings to light:

- Kids might have such a strong innate mucosal response that they are able to block the virus from entering the body

- Younger kids may have a stronger innate mucosal immune response than older ones

- Measuring blood levels of antibodies doesn’t tell us what the mucosal response will be and it’s our mucosal surfaces that provide the first line of (innate) defence against virus particles

- Adults would do well to build their innate immune responses to make their mucosal immune defences work more like those of kids – and that requires vitamin D, vitamin C and zinc, among other ‘essential’, ‘conditionally-essential’ and so-called ‘non-essential’ nutrients.

- Young kids who are exposed to the virus may be among the most effective neutralisers of the virus, so when they are in the transmission chain, they could break the transmission chain and reduce rather increase total viral loads

Australian study to Swedish reality

The role of kids as a driver of the pandemic now seems entirely misconceived. Millions of kids have been deprived of education in many countries – and may now suffer unnecessary consequences that could last a lifetime.

Worse than that, efforts to try to narrow social, educational and health inequalities among children over the last few years are likely to have been in vain. Kids from deprived backgrounds have been disproportionately impacted.

We think it’s probably just a matter of time before there’s widespread recognition that school closures and continued social distancing policies will turn out to be entirely unjustified with no upside whatsoever, just a big, drawn out series of downsides.

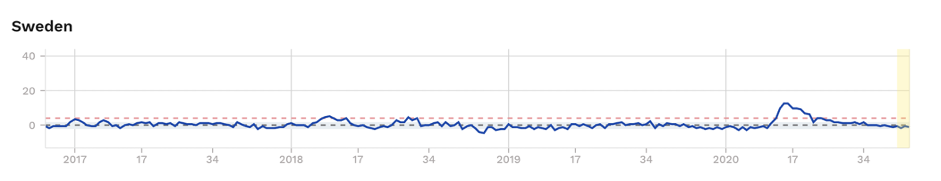

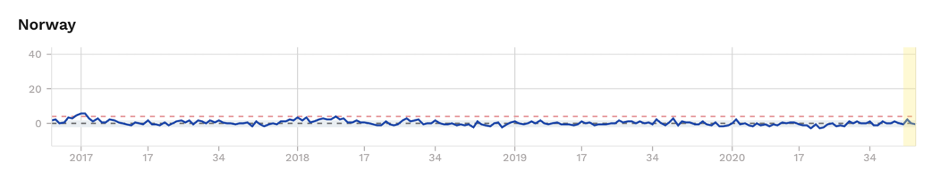

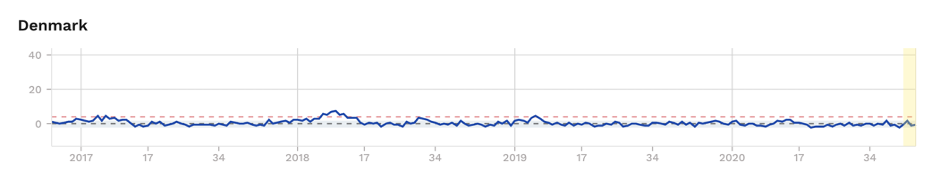

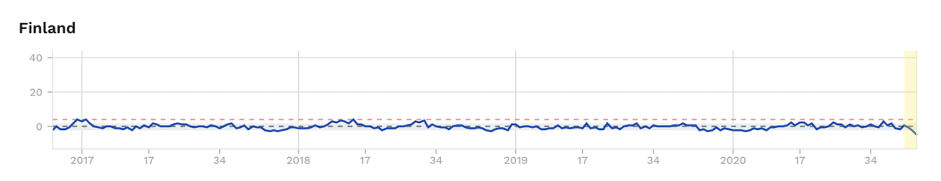

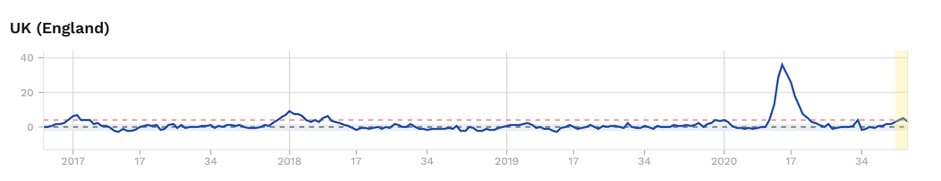

Figure 1. Excess mortality (as z-scores) for selected Scandinavian countries, with Sweden showing significant excess mortality during ‘first wave’. Source: EuroMOMO

It’s worth keeping an eye on Sweden. Remember that Sweden suffered a relatively high initial infection rate, comparable to the UK, France, Spain and Italy, unlike its Scandinavian neighbours Finland, Denmark and Norway (Fig. 1). But despite this, the light, voluntary lockdown which involved no school, restaurant or café closures, has led to no increased excess mortality since the end of May.

On top of this, the Swedish economy has been among those least impacted by the pandemic, and perhaps, in time, the same will be found to be the case with the education and development of the country’s most valuable assets: its children.

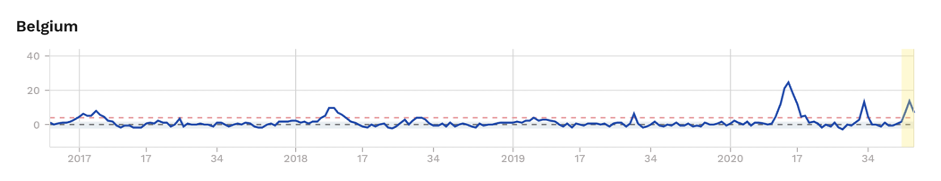

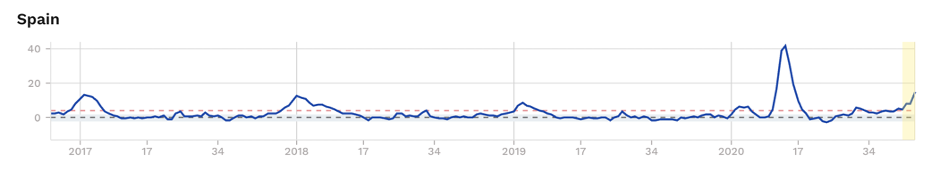

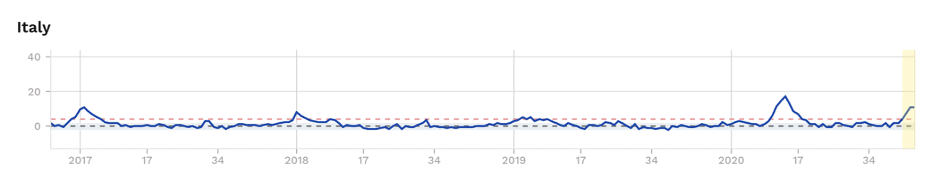

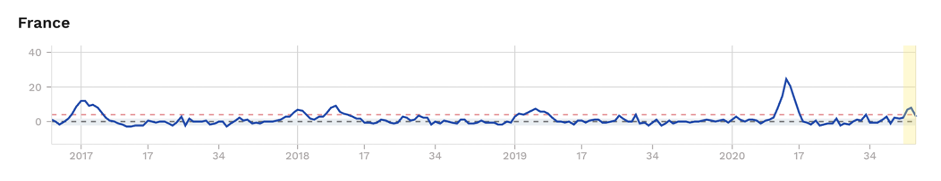

Figure 2. Excess mortality (as z-scores) for selected European countries, showing excess mortality during ‘first’ and ‘second’ waves, albeit being borderline and subject to change as recent uncertain data solidify for France and England. Source: EuroMOMO

We’ll leave you with this question: Could the kids in Sweden have played their part in blunting the second wave that’s now being felt in some other European countries (Fig. 2)?

>>> Visit our Covid Zone

>>> About ANH-Intl – brand new introductory video

>>> Please sign up for our FREE ANH-Intl Heartbeat newsletter at the base of our homepage for weekly, information-packed, potentially life-changing information

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences