Content Sections

Rob Verkerk PhD, founder, scientific & executive director, ANH-Intl

I could write a book on this subject. But for brevity’s sake I’ll just give you my top-line arguments and outline reasoning – and just 10 of them. It’s a subject I’m passionate about, inspired by 3 decades or so spent studying plants, the environment and interactions between all life forms and our natural and unnatural worlds.

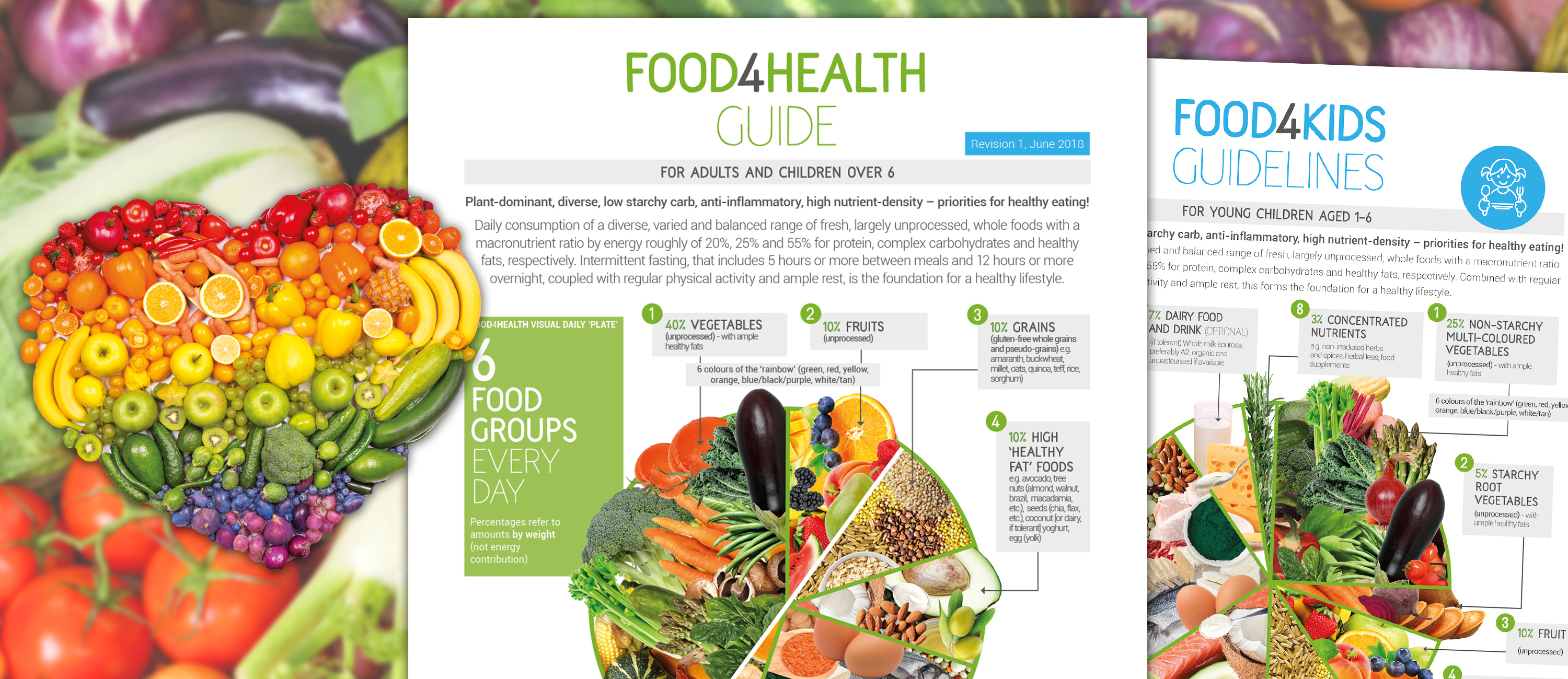

My love of food and recognition of the profound role of plant-based nutrients on health has made me a devout consumer of plant foods and herbs, both culinary and medicinal, for as long as I can remember. Recognition of my lactose intolerance in my 20s drew me towards veganism. But when health suffered through incomplete nutrition, I resumed consumption of limited amounts of specific animal-derived foods from organic and other regenerative farming systems. My diet remains what I might describe as gluten-containing grain free, plant-based, high fibre, low carbohydrate, unprocessed or minimally processed, and diverse. This equates to the eating pattern we recommend in our Food4Health guide which can just as easily be gluten-free flexitarian as it can be vegan. On our Food4Health campaign page, we have online guides for both, as well as one for children.

Given the title of this article, you’d be forgiven for thinking I was about to launch into an anti-vegan rant. While I find it impossible to ignore that we have evolved as somewhat opportunistic, nutritionally and physiologically flexible omnivores, we now face a planet on the precipice of ecological collapse and the Sixth Mass Extinction. That means it’s entirely appropriate we reconsider what we as individuals, communities, national and global populations feed ourselves given what we know about industrial agriculture.

My rant isn’t focused on veganism itself, but rather on the industrial food system that’s got in behind it. I refer to it here as Big Vegan, as it’s a far cry from the kind of veganism that relies on plant foods harvested from ‘regen ag’ systems.

Let me take you on a whistle stop of my top 10 reasons, that were among many more reasons I aired at a recent presentation I gave last month at the EU Virtual Edition of the Sustainable Food Summit.

10 reasons why Big Vegan won’t be able to keep its promises

This list is far from exhaustive, but it includes ones I think we’d all do well to be aware of when we’re cruising the aisles of supermarkets or deciding what foods we’re going to buy.

- Veganism is an exclusion diet. By removing animal products and relying heavily on all or some of a handful of commercialised and globalised staple crops such as wheat, rice, maize, soya and a few tubers like potatoes and cassava, many vegans are deficient in some nutrients. While the FAO, WHO and other international agencies set guidelines for intake of many nutrients, these are often based on inactive, healthy and often young adults and don’t take into account optimum intakes or specific needs. Nutrition gaps in protein intake and certain amino acids (e.g. arginine, leucine, histidine), essential fatty acids (e.g. Omega-3 fatty acids) and micronutrients (e.g. vitamins A, B6 and B12, zinc, selenium) are common.

- Some pasture-based livestock farming systems are already carbon net zero. That likely includes most of Scotland’s low intensity pasture-reared livestock such as Aberdeen-Angus, assuming you take fully into account the carbon capture by the grasslands on which they feed. This is a far cry from the intensive industrial feed-based beef farming systems of the USA on which much of the very high greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions data are based. It tells us that if GHG emissions are the issue, it’s not the animals that are the problem. It’s the management system used to raise them that we should be focusing on. So encouraging people to not eat meat from pasture-based livestock systems that are already net zero does nothing to assist our carbon balance sheet.

- Technological solutions rarely deliver sustainable solutions in complex systems that we manage (humans, economies, nature). It’s human nature – at least in recent times – to want a tech fix. But they don’t often deliver what they promise. Far from it. Look at the promises made in the name of GMOs. Complex systems that become unsustainable demand complex solutions. We find this in health care with diseases like obesity, type 2 diabetes and Alzheimer’s that have failed to respond to a veritable shower of Pharma’s silver bullets. We’re concerned our battle with covid-19 might also be in vain, long-term, unless we diversify our arsenal.

- The ‘Planetary Health Diet’ and the EAT-Lancet Commission report that generated it are flawed. It's the Lancet Commission that really got the ball rolling for Big Vegan. Harvard’s Prof Walter Willett and Stockholm Resilience Centre’s Prof Johan Rockström, along with another 17 scientific experts (Lancet Commissioners) and 20 co-authors, were effectively charged with finding a sweet spot for a diet that would both protect the environment and human health. They came up with the Planetary Health Diet that urged people to cut back drastically on meat (‘one burger a week’), and eat more nuts, cereals, fruit and veg. Sounds fine on the surface, but when you dig in you find significant problems with the desk-based approach that we found to be scientifically flawed. I won’t go into detail on this because we spelled it out in a 25-page report we published back in January 2019. It looked like the perfect vehicle to ignite demand for Big Food and Big Ag’s latest techno-fixes. And that’s now being driven by emerging Big Vegan.

- Human health isn’t just about what you eat. It’s also about when and how you eat. We can become obsessed with the foodstuff we choose to eat or reject. But we don’t think nearly enough about how it was grown, what happened to that plant between harvest and turning up in your house, how long it’s sat in your fridge or larder, how you’re going to prepare it – and when and how you’re going to eat it. Every single one of these steps in the process can make a huge difference in the quality of the food we eat and how it interacts with our bodies. It’s a complex interaction – and that’s one of the reasons people who change their diets can often experience no benefits, or even find themselves going in the wrong direction. Eating foods from ‘regen ag’ systems, minimising or avoiding their processing, eating them fresh, fermented or in a timely manner, not crucifying them with excess heat so generating carcinogens – in the right, unstressed environment – not too close to bed-time are just a few of the golden rules.

- The Big Vegan revolution does nothing to offset ‘obesogenic’ environments. These include the junk foods in take-outs, supermarkets, petrol stations and convenience stores that along with social determinants of health are among the biggest drivers of chronic, degenerative diseases that (even in the case of covid-19) place the biggest burdens on our health systems. In fact, junk vegan food is becoming ever more commonplace. Even if it’s not piled full of sugars, chances are it will include mechanically refined carbs (even so-called ‘complex’ oligo- or poly-saccharide ones) that trigger a blood-sugar response much like the consumption of disaccharide sugars.

- Big Vegan will likely contribute to the damaging effects of monoculture wheat, soya and maize, as well as other monocultures, many of which destroy biodiversity. Monocultures are bad for the environment….end of. They destroy soils, they are often dependent on large agrochemical inputs such as glyphosate (as a herbicide and dessicant) and fungicides that wipe out soil microbial life. Their lack of diversity and insecticide inputs kill off natural predators and parasites of pests, maintaining the pesticide spiral. Agroecological diversity and lack of synthetic chemical inputs is key to a regen ag system and Big Vegan doesn’t do regen ag.

- Decarbonising agriculture doesn’t just involve reducing emissions. It also involves increasing carbon capture. This one drives me particularly mad. Grab any newspaper and read one of the many articles that’s trashing red meat. It’ll focus on emissions and say nothing about carbon capture or sequestration by the land on which the animals are raised. That might be OK if it’s in a dustbowl. But it’s madness in a rich pasture. Here’s one from the UK’s Independent newspaper for good measure. It’s all about carbon footprints, that of beef being 17 times higher than wheat, ignoring what particular management system applies to the beef and wheat system in question. It’s also talks of the deforestation of the Amazon for beef farming (a well-known fact), but ignores the same destruction caused by soya farming. This kind of reporting has the signature of Big Vegan on it.

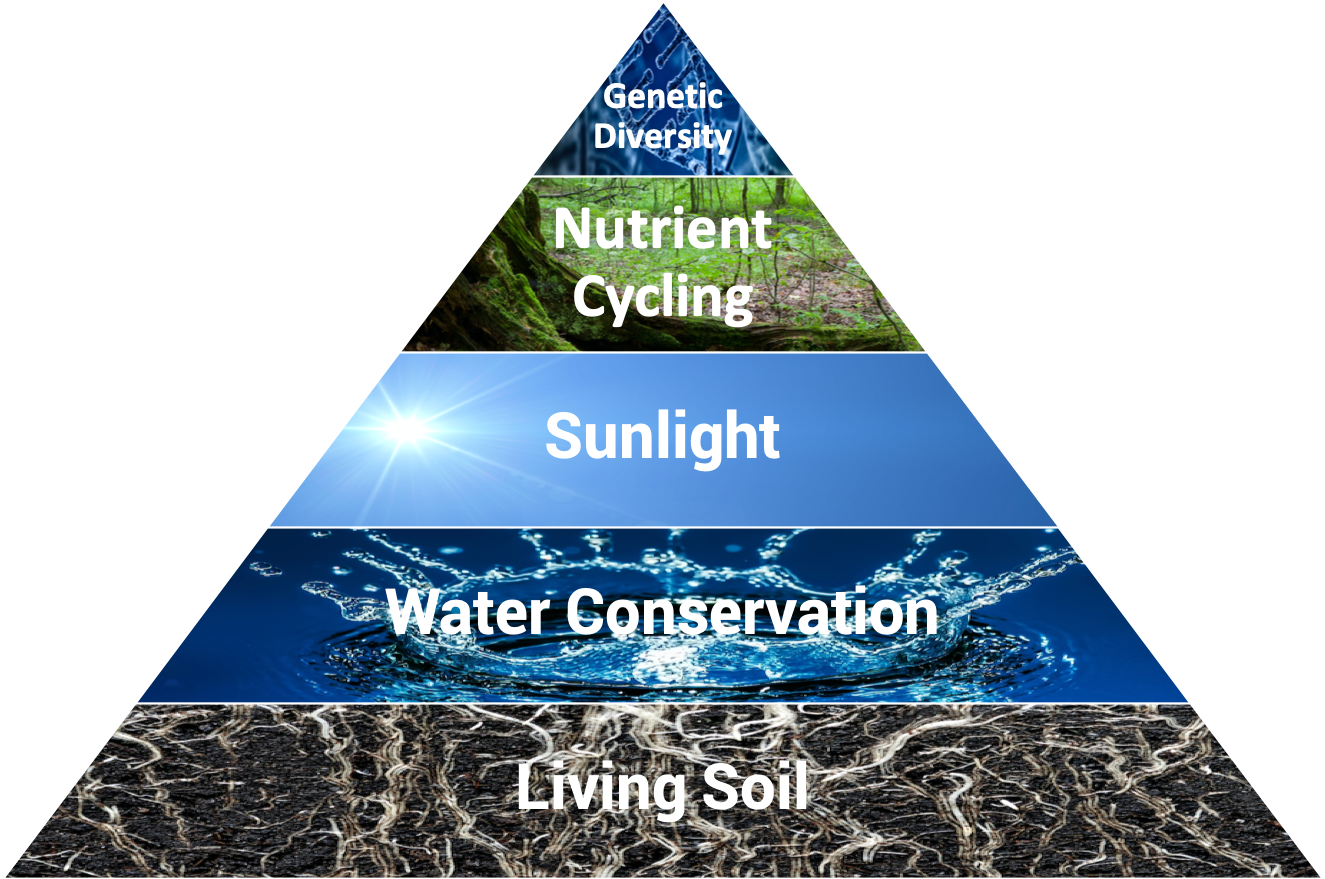

- Livestock can be vital to the regeneration of, and creation of, living soils. Talk to any mixed regen ag farmer. They’ll tell you that you can’t create a rich organic soil without animal manure. Similarly, many keen home gardeners have discovered that animal poop and pee work wonders in the compost and these composts make for very healthy veg. It’s actually all a bit Lion King – akin to the Circle of Life. Healthy natural or agro-ecosystems, as I discovered during my decade of research on them, benefit from incredibly complex interactions between plants, herbivores, successive carnivore feeding levels, and microbes. They then need organic matter-rich, living soils that retain adequate water and sunshine. They have no intrinsic need for synthetic pesticides or fertilisers, just like we don’t have a physiological need for pharmaceutical drugs. Taking animals out of the equation (whether or not you choose to consume them or parts of them), however, is a tough proposition if a stable, sustainable system is the goal.

- Halving or eliminating meat consumption and increasing cereal, nut, fruit and veg consumption can have negative impacts on the environment and agricultural sector. You’ve always got to put on your substitution hat. If you take something substantial out of someone’s diet, what are they going to replace it with? We make big assumptions, as I’ve suggested above, when we say all meat is ‘bad’ and all plants are ‘good’. Monoculture cereals, as I’ve also alluded to, can decimate soils and biodiversity. Some intensive horticulture systems that produce fruit and veg for the hypermarkets of the world are a million miles from being environmentally friendly. Tree nut farming can be far from sustainable and increased demand may decimate sensitive forest habitats. We need to stop making assumptions and understand a whole lot more about which systems are adapted to particular crops and farming systems.

The stigmatisation of red meat

I can’t help, after this final point, saying that’s it, in a nutshell. But it would be remiss of me to not make further mention of the ongoing negative science around the health effects of red meat and even the stigmatisation of red meat eating.

Looking closely at this science as I have over the last decade or so, it is riddled with confounding factors. Most particularly, the fact that people from more deprived communities eat the cheapest, most intensively reared meats that are then cooked in ways that yield carcinogenic compounds like heterocyclic amines and polyaromatic hydrocarbons. Then you’ve got the nitroso compounds from synthetic nitrates or nitrite preservatives in the majority of processed red meats. The big observational studies that have been the basis for giving red meat such a rap fail to take into account what might be regarded as healthy ways of eating quality red meats from pasture-reared livestock systems.

If that weren’t enough, a paper published last month in the journal Cancer Discovery identified a mechanism that might drive the association between red meat eating, whether processed or unprocessed, and colorectal cancer. It was related to a particular ‘alkylating’ signature that was detected in cells in the colon of people who ate the greatest amounts of red meat and went on to develop colorectal cancer. This is the most common cancer in both men and women in most Western countries.

What the paper did is elucidate for us a genomic mechanism for the DNA damage associated with dietary patterns that we’ve known for some time induce colorectal cancer, namely diets with very high intakes of red meat including a lot of cheap, processed meats. This can happen in 2 main ways: through the alkylation of haem iron in unprocessed meats that produces highly carcinogenic n-nitroso compounds – or the delivery of n-nitroso compounds directly from processed meats rich in synthetic nitrates/nitrites.

The data in this study come from well-known long-term follow-up studies; the Nurses’ Health Studies I and II and the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. So no surprises that the basic findings were the same. More interestingly there was no dose/response relationship. This alkylation signature was only there for the very top centile (those with the top 10% of intake of red meat: an average of about 155 grams of red meat a day, every day over the whole follow-up period). We know these very big meat-eaters often don’t consume a lot of quality plant foods, vegetables, herbs or supplements that can counteract the DNA damage. The meat is also largely from industrial farming systems (not pasture-raised) where animals are stressed and feed on feeds to which they haven’t adapted to during their evolution (e.g. GM soya, maize).

I smell a rat, a monoculture or cell-based Big Vegan one at that.

I sense that Big Vegan’s big plan is to prepare those who’re struggling to give up meat to get ready for cell-based, lab-grown meat. That’s a whole new technological game plan, one that we know delivers a different complement of nutrients to the body compared with meat from naturally-raised animals or even insects. Meat is so much more than just a source of protein (but that’s another story).

And while your meat comes out of a lab, what damage are they planning to do to our livestock-free farmlands?

The next time you’re out food shopping, remember, it’s the farming or production system from which the food has originated that’s likely more important to both your health and that of the environment than the food type itself.

Find out more

Comments

your voice counts

08 July 2021 at 3:28 pm

Great balanced article. Looking at the whole picture is what we all tend not do to, we tend to have our blinkers on and see what we want to see and disregard that which we find uncomfortable. I know I have had my eyes and ears opened to a lot of vital food facts over the last few weeks and am making changes to my diet. Balance is the key to everything, looking at everything holistically. I totally agree that food that is pure and natural is the best you can get, nature creates such perfection and it's all there for us to eat and for our health to flourish, if we so choose. I think people need to be empowered with the correct information to make the correct food choices. This education should start with our children at school. The Vegan food movement, as far as I can tell is based on lazy Veganism, there are so many vegan fast foods out there pertaining to be a health choice but so highly processed it's scary! It's highly tied in to the 'lets try to save the world' movement that I think it's a bit like wearing masks, it gives a certain signal to others that people are doing their 'bit'., when it hasn't really been fully researched or understood by the individual.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences