Content Sections

Stress gets a bad rap, but not all stress is bad. If it wasn’t for positive stress the human race wouldn’t exist as it does today. Equally, natural selection has shaped the stress response – the need to find food, pain, fever and birth. In a more modern context, think about falling in love, travel and starting in a new job. These are examples of positive or good stress. But when does stress become negative rather than positive and how do you hit the off switch when you most need to? Read on – this is the theme of our newsletter articles because it’s International Stress Awareness Week.

Whilst positive stress (eustress) helps to motivate and focus, feels manageable, enhances performance and can even feel exciting. Acute and chronic stress cause distress for many as we stretch to meet and meld ourselves with modern life and all its challenges. However, it's our reaction to chronic stress — rather than the nature of the stressor itself — that actually influences whether or not the stress will damage our mental or physical health in the longer term. And that means that we can become more stress tolerant and resilient by knowing when to hit the off switch and take some time out.

The stress response

Stress is one of our most basic survival mechanisms, which is why the stress system is a complex, sophisticated, and carefully regulated system that has been shaped by natural selection so that it can give the human species a selective advantage. This advantage has clearly been considered substantial from an evolutionary perspective in order to outweigh its huge costs.

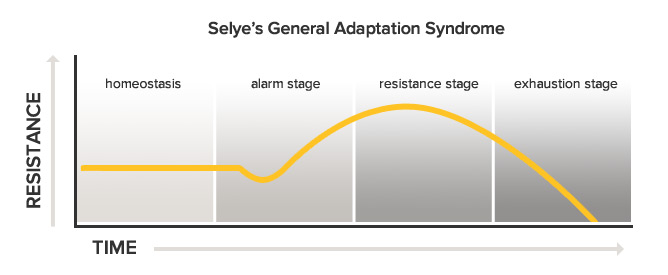

Hans Selye, often described as the ‘father of stress research’ was the first to use the term stress to describe the “nonspecific response of the body to any demand”. As part of his work he coined the term ‘general adaptation syndrome’ (GAS), which indicates that stress has some positive physiological function too.

Knowing where you are in the three stages of the GAS is important if you’re to take steps to ‘flick the off switch’ or know when you may need the support of a healthcare practitioner to help you shift gears. Do any of the following sound, or feel, familiar?

- Alarm reaction– the brain receives a distress signal triggering the release of stress hormones (adrenaline and cortisol), which activates and stimulates our sympathetic nervous system preparing us to respond to a stressor. This is your ‘fight or flight’ response

- Resistance– having reacted to a stressor the parasympathetic nervous system takes over to try and return the body to normal (homeostasis). If the stressful event ends, stress hormone levels reduce, the heart rate normalises and the physiology comes back to balance (homeostasis)

- Exhaustion– the final stage. By this time the body has depleted its resources by trying to keep ‘fighting, but is not able to recover from the initial alarm stage. Once it reaches this stage the body becomes more susceptible to disease and even death. This is where many people remain stuck, unable to resolve the body reaction because the unresolved stress is still a feature.

Source: Wikimedia Commons

Ripples through generations

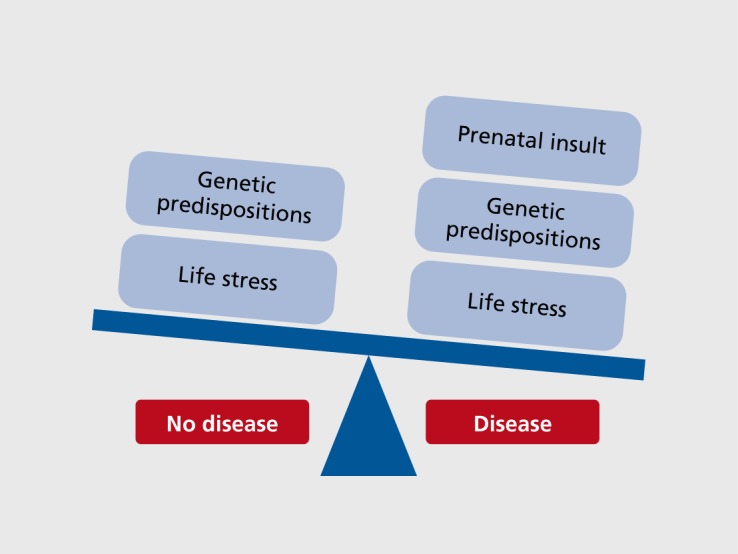

It’s not just the daily stresses and strains of life that that can affect us. Increasing evidence shows that the effects of stress and trauma can be transgenerational and pass through multiple generations. Exposure to stress and trauma in either parent can affect the epigenetic expression (genetic programming) of their children. This has been strongly associated with an increased risk of developing neurological issues in children often leading to a heightened sensitivity to stressful events, i.e. lacking stress tolerance.

Tipping the balance toward neurodevelopmental disease presentation likely depends on multiple interacting factors, ultimately combining a genetic predisposition with environmental insults experienced at key developmental/susceptible periods in life. For example, when mapped onto a given genetic variation that promotes susceptibility, an environmental exposure to prenatal stress may act as a second hit in a two- or three-hit model, where the next stress insult experienced during later points in life tips the scale in the direction of disease onset. In such a model, the prenatal exposure to stress is acting as a point of epigenetic programming due to an increased genetic vulnerability that when added together leads to sensitivity to later life perturbations.

Source: Fig 1 from Lifetime stress experience: transgenerational epigenetics and germ cell programming

How do you know you’re stressed - and not in a good way?

Distress refers to negative stress be it from environmental (temperature changes, noise, pollution), chemical (smoking, alcohol, drugs – medical or illegal), social (family, society) or workplace (high demand, lack of job satisfaction, lack of control) sources. Negative stress;

- Causes anxiety and concern

- Can be short- or long-term

- Reduces our ability to cope

- Feels bad

- Reduces our ability to perform well

- Can lead to both mental, emotional and physical health issues

If you’re someone that’s susceptible to chronic stress, why not test your level of wellbeing with The Ryff Scale?

How do you hit the off switch?

It’s impossible to eliminate stress from our lives, and we really wouldn’t want to given how necessary positive stress is to us. But, if your stress strays into overwhelm, there are ways to manage it more effectively and build your resilience and your stress tolerance. Here are some suggestions:

- Get outside and take a ‘forest bath’, connecting to nature with all your senses

- Move your body with some physical activity – but make sure it’s something you enjoy

- Prioritise your nutrition by eating natural, nutrient dense, unprocessed (organic where possible) wholefoods to nourish and support your body particularly during stressful periods

- Take some ‘me’ time – solo time out allows you to pause, reflect and refresh. A walk, sitting on a park bench or standing barefoot on the grass will help ground you

- Be aware of your breath and practice deep breathing to bring you back into your centre again

- Engage in mindfulness techniques and find time to meditate – there are lots of great apps around

- Take a digital detox and go tech free for a few hours or a weekend

- Learn to say no when you need to

- Have some fun and laugh a lot!

Resources

- Test your level of wellbeing with The Ryff Scale

- Why Zebras Don’t Get Ulcers by Robert M. Sapolsky

- The Stress Solution by Dr Rangan Chatterjee (due for release December 27th, 2018)

- Self-regulation techniques using HRV with HeartMath to become more stress resilient

- Meditation apps

Comments

your voice counts

08 November 2018 at 2:51 am

Stress is caused by the millions of negative emotions and thoughts pounding back and forth between the conscious and subconscious every second. Active meditation done for 15 minutes every day, will,after a few weeks, permanently slow your brain-waves to Alpha, 8-12 cycles per second.. this eliminating clutter. The clutter is the millions of positive and negative thoughts and emotions moving between conscious and subconscious a second.. creating stress,, fear, depression, confusion, poor decision making etc. The newly, trained neutral, calm mind then can pause before any decision making, and wait for the subconscious to respond. The 1st thought will be the correct answer,. Modern psychology(psychiatry/neurology doesn't yet know of this. (My son is in neurology).

The method of doing this advanced meditation is written up in The Pleiadian Mission by R Winters based on input from Swiss Billy Meier of theyfly.com. I have been doing this for over 15 years. No, I'm not selling anything just getting you up to speed if you have an open mind and my comment isn't deleted.. as it usually is.

08 November 2018 at 8:10 am

Hi Thomas

Thanks for your insights. Very helpful, particularly for anyone new to the benefits of meditation.

Warm Regards

Melissa

08 November 2018 at 12:40 pm

Embracing stress is an inner balancing within the wholeness of being this moment - so yes - if the reaction to alarm initiates a loss of presence - release it as a basis for action or decision and seek the conditions in which an embracing and centring balance rises as your own.

Distress is reaction persisted in without being cleared, reintegrated, or undone. Perhaps as a repetitive loop of the triggering alarm acting as a forceful denial of the capacity or freedom to relax and release to presence.

The capacity to bear or abide with is the capacity to undo or be healed of.

The attempt to put out a part of ourself as if to get rid of it is the making of a world in which we have no belonging and to be outside our true environment is a pain of isolation that cannot be altogether masked over.

The psychic-emotional is 'masked' by the term 'psychological'.

And this attempt to project out from our self as if to then study and control it from 'outside' is a dissociation given power.

The 'sacrifice' of vital consciousness to a mental modelling given identity, is the fear of loss of identity to the true (awareness) of being. And so conflict and division operates the capacity to limit and block awareness of true - perceived as the greater threat. Yet this cannot be openly accepted and still function as protector and so demands sacrifice of true witness to protect the protector - and so it is that "from he who has not shall more be taken - even the little that he has". Not by God but by a false sense of self-sacrifice in a gesture of protection willingly engaged as if the lesser evil.

This is 'deep' - but consider the protection racket as the underlying model of society - that is being exposed in Pharma, but no less in banking, food production, or technological networks of further dislocation and replacement by systems that promise protections while demanding sacrifice.

Peace is the immediate result of an aligning of purpose in truth. The symptoms or drama may persist in various forms, but perspective has been restored and the 'siege' is broken or at least lifted in the taking of a truly guided step. Guided steps may be served by recognizing 'inner conflict' or struggle as an indicator of following the wrong guide - and initiating the willingness to release it to open to the true.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences