Content Sections

By Meleni Aldridge BSc NutrMed Dip cPNI

Executive coordinator, ANH-Intl

One of the most common symptoms of gut dysregulation suffered by many people, and rising, is heartburn (indigestion) and the range of other symptoms caused by acid reflux or gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) as it’s termed medically. But is it really caused by an overproduction of stomach acid and what happens when we live on drugs in an effort to ‘put the fire out’?

Before we dive into this article, let’s just clarify some terminology.

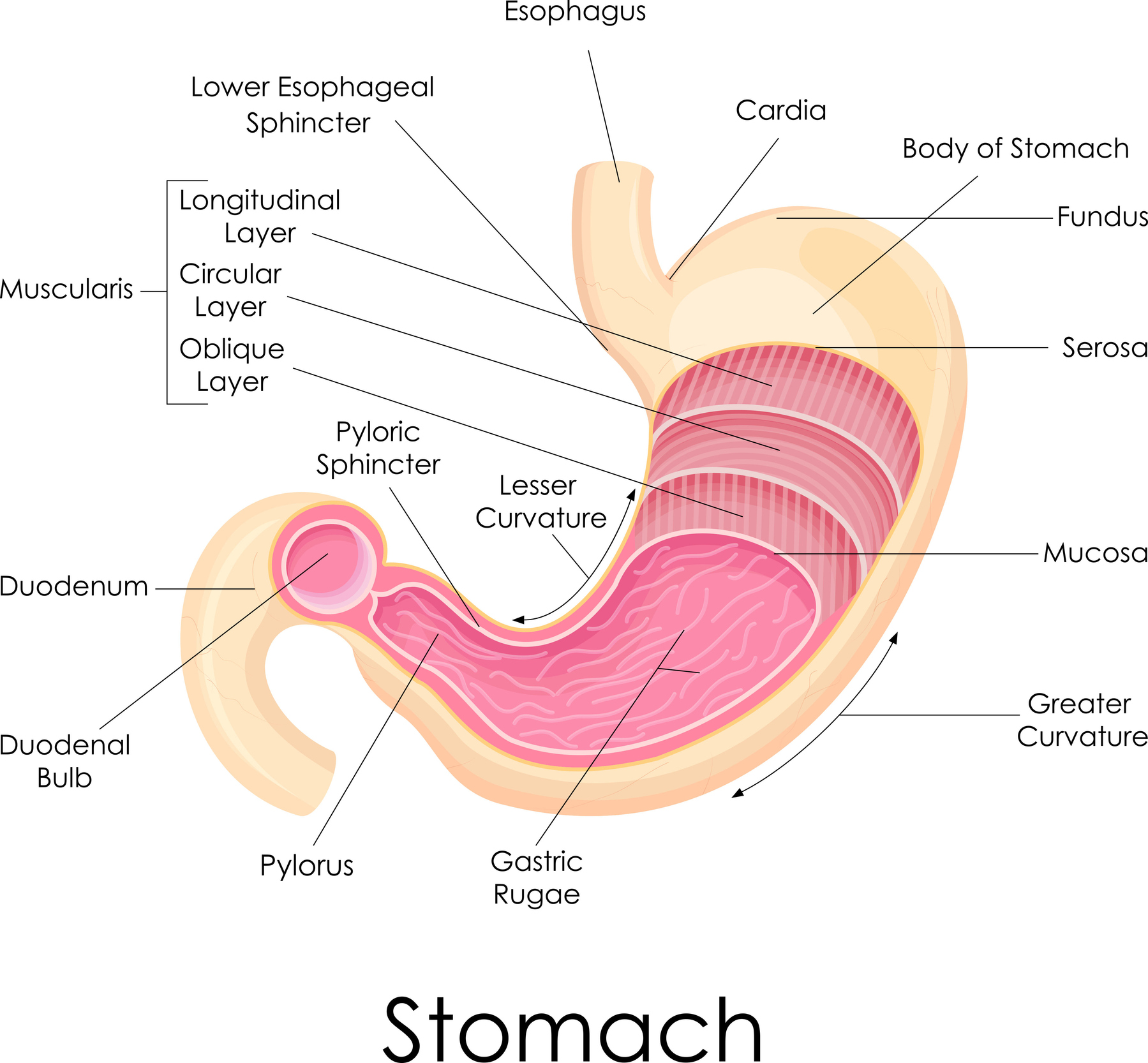

Heartburn and indigestion are one and the same and caused by an irritation of the oesophagus (the tube from your mouth to your stomach) due to the reflux of stomach acid and undigested food leaking back through the lower oesophageal sphincter (the valve at the top of your stomach). Symptoms include a burning sensation in the chest, an acidic taste in the mouth, and sometimes a sore throat. This can play havoc with one’s vocal cords as well and singers are especially careful to avoid heartburn or reflux.

GERD or gastroesophageal reflux disease is the name of the condition in which you suffer reflux — heartburn being just one of the potentially many symptoms. GERD is characterised by a range of symptoms that can include heartburn, chest pain, difficulty swallowing, chronic coughing, asthma, throat irritation and a hoarse voice.

Lastly, depending on which side of the pond you live, you may say oesophagus (UK) or esophagus (US) and gastroesophageal reflux - GERD (US) or gastro-oesphageal reflux - GORD (UK), although GERD is more commonly used now. Whichever way you spell it, they're the same thing!

Conventional treatments

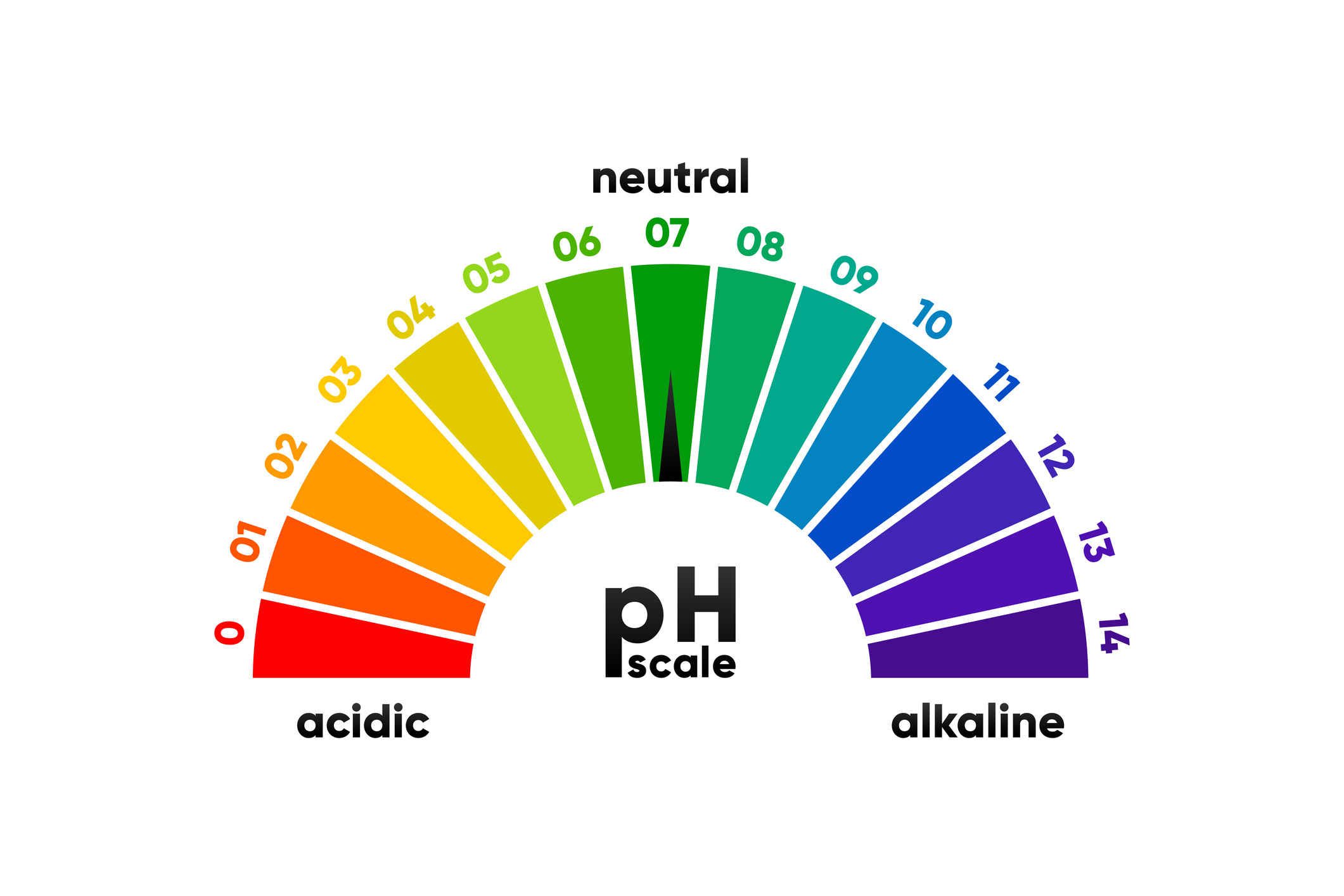

The main over-the-counter (OTC) medication that’s widely available are antacids as liquids (think Gaviscon) or pills (think Rennies). Antacids are taken orally to increase the pH of the digestive system to reduce or prevent stomach acidity or heartburn. They work by binding stomach acid, neutralising it or simply providing an external coating. Gaviscon for instance has two main components – one forms a barrier to stop acid release, second is an antacid. Common ingredients in antacid tablets include aluminium hydroxide and magnesium hydroxide, while liquid antacids typically contain sodium citrate, sodium bicarbonate or magaldrate, an aluminium-containing antacid.

If you visit your doctor for help, you’ll likely be prescribed a drug that belongs to a group called proton pump inhibitors (PPIs), which reduce the amount of acid produced in the stomach. Also known as acid-suppressing drugs, PPIs are commonly used to treat GERD, peptic ulcers and routinely co-prescribed with anti-inflammatories and other drugs that can irritate the gut. PPIs are also used to treat conditions such as Zollinger-Ellison syndrome, where the stomach produces too much acid. They work by blocking the enzyme system responsible for producing acid in the stomach, but unsurprisingly this has multiple downstream effects for the entire digestive system. Common PPI drugs are omeprazole, lansoprazole, zegerid and esomeprazole.

Why is pH so important?

One of the body’s top priorities is to maintain appropriate pH in blood, tissues and organs to maintain optimal homeostasis (balance). Different tissues and organs function at different pHs so it’s not as simple a case as just "becoming alkaline" or “less acidic”. Having the right pH in the right places is critically important because it affects the way in which many substances are absorbed, distributed, metabolised, and excreted by your body. It’s also a question of having the right acid-base balance in the right places to be disease-free — and healthy.

The appropriate pH for a given organ or tissue or system also critically influences the rate at which enzymes and other proteins can work in the body, which is why naturopaths and nutrition practitioners are so focused on this particular area of health. Maintaining a careful balance of pH helps the body to regulate the many biochemical reactions that occur, and helps the body maintain its balance (what is scientifically referred to as homeostasis). An unbalanced pH in a given body compartment leads to dysfunction, dysregulation and eventually disease. Particularly those diseases associated with acidosis or alkalosis, which is why our kidneys, hearts and lungs are both so vital and so at risk, as well as the gut and its associated organs.

The normal pH of our blood is pH 7.35 – 7.45, which is mildly alkaline. Metabolic acidosis, a build-up of acids in the blood and tissues (defined by a serum bicarbonate concentration of <22 mmol/L) is often the result of early-stage, chronic kidney disease. The acid-base balance is controlled primarily by our lungs and kidneys and then with secondary chemical buffers.

As we age, the risk of metabolic acidosis and muscle loss (sarcopenia) increases and with it, our risk of other diseases. A recent Japanese study in 2021 found that low urine pH of 5.5 was consistent in the elderly with muscle loss, whereas a urine pH of 6.2 was consistent for those without it. If you maintain muscle mass, you are less likely to become acidic as you get older because the mitochondria are able to produce enough energy to push all the buffer pumps. It also helps if you load your body with alkaline vegetable foods. So you can see that the body is so sensitive, even a slight shift either side of the normal pH can make an enormous difference.

Our lungs, kidneys and chemical buffers (e.g. bicarbonate) need a ‘pump’ and they need energy to power that pump. The bicarbonate pumps open the ion channels to bring in bicarbonate to reduce acidity and buffer the hydrogen ions that are being produced continually through cellular respiration (Krebs cycle), gastric acid production and even breathing. Our kidneys are always going to be more acidic as they’re so key in the conversion of hydrogen ions. That's why measuring urine pH isn't a useful measure of blood pH — in fact it can be very misleading.

Even carbon dioxide (CO2) creates acidity as it diffuses into the lungs so our bodies are having to work continuously to maintain appropriate pH. It’s interesting that people who have low muscle mass, generally also have poor lung function as exercise helps you maintain your lung function. If you have poor lung function, you can’t adequately get rid of CO2 and bring enough oxygen in. This why shallow breathers (and mask wearers!) are at risk of a host of other health issues.

Is heartburn caused by too much acid?

The normal acid in the stomach is around a pH of 3 and if you have too little (low) stomach acid (hypochlorhydria) your pH is likely to be between 3 and 5. Now here’s the kicker that seems to be the most well-kept secret that isn’t taught at med school…

In most instances acid reflux and heartburn is caused by too little stomach acid — not too much.

This causes the stomach to empty slower (gastroparesis) because it doesn’t have sufficient acid to digest the food in it. Slower emptying means that food stays in the stomach way longer and if the lower oesophageal sphincter relaxes inappropriately, you end up with food regurgitation, but also a burning sensation from the acid moving out of the stomach and up the oesophagus. Over time, there can be longer term complications from the increased inflammation such as bleeding, ulcers and even a risk of cancer.

The dysfunction that causes the lower oesophageal sphincter to relax at the wrong time is due to intra-abdominal pressure and that’s caused by… guess what? Low stomach acid. A higher pH in the stomach can allow bacteria to proliferate that shouldn’t be there and also allow poor digestion of carbohydrates, both of which cause a build-up of gas, which increases the pressure, causing the sphincter to relax. This is why if you burp a lot soon after eating, it’s an indication that your stomach acid is likely too low. Then of course, the usual suspects like alcohol, smoking, caffeine, obesity, pregnancy and some other drugs can all contribute to pressure on the lower oesophageal sphincter.

Slower stomach emptying also affects the rest of the digestive tract because a) you may not have eliminated any pathogens in your food sufficiently and b) the signal to your pancreas to release the enzymes essential for breaking down your food may not happen at the right time. The downstream suite of health effects from low stomach acid include, lack of absorption of nutrients, mineral and vitamin deficiencies, microbiome dysfunction, bloating, pain, wind, burping, heartburn, neurological conditions, mental health imbalance and fatigue.

Low stomach acid can also contribute to much more serious health problems such as autoimmune conditions, osteoporosis, skin conditions, allergies and food intolerances, SIBO (small intestinal bacterial overgrowth) and inflammatory bowel disorders (IBD).

Stomach acid production also declines with age, yet PPIs are still routinely prescribed for GERD. If low stomach acid puts us at such a health risk, why are they still being prescribed so widely — and why are people being left on them for years, even decades in many cases?

Risks of taking PPIs long-term

With the rise of long-term use of PPIs, to reduce stomach acid production, there has been a corresponding rise in reports of cardiovascular risks well-known to be associated with this medication. Chronic PPI use may be linked to an increased risk of cardiovascular events, such as stroke, heart attack and even death, as well as increasing the risk of dying from a heart attack, rather than surviving it.

For example, an observational 2021 study published in the Mayo Clinic of Proceedings found that regular long-term users of PPIs of more than 5 years had over double the risk of cardiovascular disease and heart failure than non-users. Even short-term users (1 day to 3.8 years) had a 20-25% increased risk. More than that, many didn't even meet the criteria for taking them in the first place. This study followed up 4,500 elderly patients in the real world from 1987 to 2016 where they all started with being free of CVD. Another study linked PPI use in people with Type 2 diabetes with an increased risk of cardiovascular events and mortality.

PPIs are unfortunately still the most commonly prescribed drugs for the treatment of GERD and other stomach acid-related disorders, despite what we know about the importance of stomach acid. They’re designed to reduce stomach acid production by targeting the proton pumps, or hydrogen/potassium ATPase pumps, within the stomach cells to relieve heartburn and the other GERD symptoms. Whilst alleviating symptoms is good for people short term, too many are living on these drugs for years and they're subject to widespread misuse.

The most common adverse effects of taking OTC antacids, apart from those listed above that relate to low stomach acid, include diarrhoea, constipation, nausea, headaches, and decreased absorption of certain nutrients. Long-term use of antacids can also lead to an imbalance of minerals, like calcium, iron, magnesium, and potassium, which can result in further multiplicity of health problems. In rare cases, people may experience an allergic reaction to active ingredients in antacid formulations, which can cause rashes, difficulty breathing, and hives. Some of these products are loaded with aluminium.

The acknowledged, common, side effects of PPIs include headaches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, constipation, and rashes. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors are acknowledged to increase the risk of abdominal pain, wind, dry mouth, dizziness, and kidney problems. People taking long-term PPIs are also at risk of low magnesium levels in the blood, which can lead to muscle spasms, irregular heart rhythms, fatigue, and an increased risk of bone fractures. Long-term use of proton pump inhibitors may also be associated with an increased risk for developing Clostridium difficile infections, pneumonia, small intestinal bacterial overgrowth (SIBO), and the acquisition of drug resistant microorganisms.

So, what to do for GERD naturally?

Our bodies have been designed around the ability to consume food, break it down, digest it and liberate the nutrients. It’s the most natural thing in the world so it stands to reason that there are many natural ways to support digestion and maintain an optimal pH. Yes, it’s tougher in the modern world with all our new-to-nature foods, chemicals, toxins and overwhelming load of stressors, but it’s still possible when you know what to prioritise.

Here are some key pointers to bear in mind:

- First and foremost, if you're a user of PPIs and would like to come off them, please don't do this alone. Please do this with the help of an appropriately trained health professional and talk to your doctor. It is possible to come off them, but needs to be done slowly, whilst introducing a new support system for your digestive tract

- A good nutritional programme is essential – high plant food-based diet, with plenty of vegetables (as per our book, Reset Eating), whilst not ignoring good quality proteins and healthy fats. Starchy, refined, sugary carbs are not your friend and need to be ditched!

- Citrus juice e.g. lemon in hot water, is at least as effective as sodium bicarbonate to treat metabolic acidosis. Start your day with some fresh lemon in hot water. Lemon is a natural source of citric acid, which is an acidic compound. However, once it's been metabolised through your digestive tract, the citric acid is converted into the alkaline compound, sodium citrate, which has an alkalising effect on your body

- If you've been taking antacids, as against PPIs, try a tablespoon of raw apple cider vinegar in a small amount of tepid water half an hour before eating to boost your stomach acid and assist digestion

- Stress management is not just key to supporting good digestion, it's critical:

- Try getting out in Nature on a regular basis and explore some forest bathing

- Get some quality 'me time' with some regular mindfulness and a guided meditation journey or two

- Exercise outdoors rather than indoors to lower inflammation and increase stress release - we're still being powered by our hunter/gather genome and indoors gyms just don't have the same health benefits

- Incorporate activity that focuses on breathwork like yoga or pilates to build better lung function and a properly functioning diaphragm

- Did you know that humming tones the vagal nerve for better gut/brain connection and neural signalling? That's why since time immemorial yogis, holy orders and groups have come together to chant and sing. It not only allows you drop into a deeper connection with yourself and the Divine, but is also good for your health. Singing - on your own or in a group, is wonderful for lung function as well as stress management

- Prioritise sleep:

- Visiting a musculo-skeletal/physical/manipulative practitioner e.g. an osteopath, chiropractor, cranial sacral therapist, to ensure that you have proper skeletal and muscle alignment in your chest area and no impingment on the diaphragm

- Mindful eating. Take time to cook from scratch to get those digestive juices going, then eat at the table and take time to chew each mouthful thoroughly to savour the food you're eating and give your body time to produce plenty of acid and enzymes to digest your food properly

- There's a wide range of herbs, enzymes and other supplements to support good digestive function. It's always best to consult with a nutritional practitioner who can advise on the best support for your particular needs and also run some functional tests to individualise your protocol.

Here are a few safe (use as directed on pack) and easily available digestive food/dietary supplements to support stomach acid production and good digestion:

-

- Digestive bitters - a collection of bitter herbs used for hundreds of years to stimulate good digestion and in particular, production of digestive enzymes

- Digestive enzymes - additional support for your own enzymes in a capsule

- Betaine hydrochloride (HCl) - this is naturally derived from beets and helps to breakdown food in the stomach like your own stomach acid. Start at the lowest dose and work up if you need additional support. Often labelled to take it at the start of a meal, I was given a tip a number of years ago by Dr Bob Marshall of Premier Research labs (now deceased) to take it just after you've finished a meal and it's been so effective that I've followed his advice since. See what works best for you, as per the label or just after, it's a great supplement to support good digestion at the start of the digestive tract

- Zinc - making sure you have adequate zinc levels isn't only good for your immune system, it's an essential co-factor in making stomach acid too

- A teaspoon of good quality honey in warm water or chamomile tea can be helpful for heartburn as it coats the oesophaghus. It's widely used in Ayurveda for oesophagitis because it's so anti-inflammatory

- Lastly, use as many fresh herbs and some spices in your cooking to support digestion e.g. rosemary, fennel, ginger, turmeric, peppermint, oregano, basil and garlic. Drinking infusions of ginger, fresh turmeric and herbs between your meals is also helpful. Nature's medicine cabinet is there to be explored!

>>> Get started on your journey to improved digestive health and overall wellness with a copy of our book RESET EATING

Comments

your voice counts

23 June 2023 at 6:47 pm

A brilliant article; I recall reading 'Why Stomach Acid is Good for You' by Jonathan V Wright and Lane Lenard in 2014. They made a key point when they wrote their book - the Ant-Acid market is worth $7bn (probably a lot more now). This class of medicine is dished out like candy either on its own or often with other medicines and patients have no idea about the long term side effects. It is so sad that people do not research what they are putting in their bodies, but instead place their trust in organisations who are keen to please their shareholders.

26 June 2023 at 3:47 pm

Thank you Sarah. Totally agree, these drugs have become so commonplace and people just have no idea of the ramifications. It's a massive market now, but Dr Wright saw the writing on the wall all those years ago. Stomach acid is very good for us!

Warm wishes

Meleni

23 June 2023 at 8:35 pm

"Whilst alleviating symptoms is good for people short term, too many are living on these drugs for years and they're subject to widespread misuse", I read in the above text. But if the cause of GERD is low stomach acid, how lowering it even more with PPI drugs can constitute a short term relieve? Shouldn't it aggravate the problem even more?

24 June 2023 at 11:45 am

For instance in my case the gastric reflux starts many hours after I've been sleeping, there is absolutely no food in my stomach, but acid continues to be produced because I am a chronic anxious type of person, Stress and anxiety can be another reason for the GERD, as I am sure many others causes like the microbe flora in the stomach, malfunctions of other related organs like the liver or the pancreas. The situation here is that no one can reduce the GERD to a single origin, there are many.

28 June 2023 at 10:57 pm

Your comment reinforces why it's so important to see an appropriately trained health professional so that they can rule out other potential aggravating factors and support a return to healthy digestion. When there is low stomach acid, food can stay in the stomach for much longer than expected. The good news is that there are many ways to rebalance digestion and the gut can respond relatively quickly.

Warm wishes

Meleni

28 June 2023 at 10:47 pm

Yes, absolutely. Over time the use of PPIs aggravates a low stomach acid condition, which is why there is so much concern over prolonged use and people just being left on permanent prescription.

Warm wishes

Meleni

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences