Two is the number that springs to mind when I reflect on my weekend challenge of cycling from the London to Paris in under 24 hours to arrive at the finale of the Tour de France on the Champs-Élysées.

My vehicle had two wheels and two pedals. It took two attempts. There were two legs: a UK one and a French one, adding up to double century in miles. I had two meals during the 24 hour period. And, probably most importantly I consumed two carbohydrate gels. That latter fact is probably most relevant to the theme of this article that is about how to combine (relatively) low carbohydrate diets with exercise, using ‘nutritional ketosis’ (i.e. to ‘keto-adapt’) to enhance your wellbeing and make endurance challenges much more achievable.

A great number of people understand the value of good nutrition. Probably not a dissimilar number appreciate the value of regular physical activity and have turned their backs on sedentary lifestyles. But many fewer have found ways of combining these two vital planks of health and wellbeing (the third is of course all about sleep, rest and peace of mind) in such a way that that it makes it relatively easy to fit all of this into a busy life.

That’s why we thought it might be valuable to offer an account of my weekend adventure and the preparation that led up to it. While my own adventure involved a bicycle, the same approach could be equally applied to any endurance activity, be it trekking, mountain climbing, kayaking – or something I learned of recently – 24-hour, non-stop, stand-up comedy!

About to leave home in Hampshire, UK, at 7 pm, Saturday evening

Picture this

You know when you get it right. It’s a special feeling when your body and your bike work as one. The fresh air washes around you, leaving in its wake the residual stress from your hectic week. The hum of the tyres on the road and mechanical whirr of your freshly oiled chain and gears are the only indicators that your forward movement is being assisted.

Your breathing is steady and deep. Your torso and core feel good, strong and light, not being weighed down by food or digestive processes. You’re running on empty, but your fat reserves and ketones are burning cleanly, propelling you forward at a surprisingly rapid speed. Your legs feel powerful and you know they can deliver the goods for hours to come, regardless of the hills thrown up in front of you.

After over 3 hours in the saddle, drinking nothing other than water with electrolyte salts added, you have no inclination to feast on cake or even down a gel. Your body has learned to use fuel from its own fat stores, and you know the fat burning will continue well after you finish your ride. This is how it feels to be a keto-adapted cyclist. And this is how my 200 mile in 24 hours weekend adventure felt, even when I knew I had to really crank up the pace, between the red lights and traffic, to make into the centre of Paris before the expiry of self-imposed 24-hour time limit! It means developing real metabolic flexibility so that you can switch between burning fat, carbs, or even in some instances protein, when the need arises.

Developing metabolic flexibility and having the capacity to use ketones and lipid reserves in the body as a source of fuel in the face of low carbohydrate availability, the process referred to as keto-adapatation, is actually the system we’ve been gifted by our ancestors. In many of us, especially in Westernised cultures, the system falls into disuse through our frequent over-eating and our over-exposure to carbohydrate-based foods.

For many non-professional cyclists, who regularly consume carb-based gels while riding – or fill their water bottles with carb and sugar solutions – the body never has any need to switch to fat-burning during exercise.

24 hours in numbers

I am both a critic and supporter of the ‘n = 1’ approach to the medical and sports sciences. It’s problematic because a single individual is about as far way as you can get from a representative sample of the population. But it also has its place. That’s because when you learn of large numbers of individuals doing similar things, achieving similar results, this provides meaningful information. This kind of information is ignored at your peril, and can, of course (and ideally) be scrutinised further under more controlled, scientific conditions at some later stage.

The n = 1 approach also has value because of the power of story. We know that people are more likely to adjust their diets or lifestyles if someone close to them has had a positive experience. This may influence them more than a multi-centre, randomised controlled trial (RCT), a lay summary of which they might encounter in the Sunday newspaper.

Among the UK-based cycling community, it’s become quite a challenge to get from London to Paris, complete with the cross-Channel ferry journey inside 24 hours. The most common Channel crossing is Newhaven-Dieppe because it’s short.

I actually attempted this last Friday night. There were torrential downpours, traffic was stationary in London, I got 3 punctures in one hour – and I aborted the ride!

I decided to give it a go 24 hours later. But by that time all the sub-4-hour express crossings were booked – yes, it was the weekend of the Tour de France ‘grand finale’ and many a Brit wanted to see Chris Froome ride in to victory! The only boat I could find was from Portsmouth, and it involved an 8½ hour ferry crossing, which would dig deep into my cycling time. I knew I’d have to ride hard and the forecast predicted heavy rain and wind on the French leg. The long ferry journey along with the headwind, rain and the fact I was riding solo and couldn’t get up to 40% advantage by reducing wind resistance by drafting a rider in front would make the odds in me succeeding in the bid somewhat slimmer than they might have been.

The long and short of it was that I pushed hard on the bike (well, at 75% of my maximum, as measured by my heart rate) in appalling conditions involving torrential rain and headwinds for around 80% of the ride. I got lost several times and had to backtrack to find my way around forest systems that ran out of roads suitable for a road bike. (The moral of that story is don’t just download a Google Maps route set for cycling as it incorporates trails suitable only for mountain bikes!)

After around 8 hours of cycling, I entered the outskirts of Paris. I was confronted by large amounts of traffic, endless, unsynchronised red lights and an unusually high concentration of humans and vehicles around the Arc de Triomphe and Champs-Élysées because of the finale of the Tour.

But I made it – with all of two minutes to spare! I used Garmin’s ‘live tracking’ service so a few family members and close friends, who elected to follow my blue radio dot across their screens, managed to virtually experience some of my own anxiety about meeting my 24-hour deadline!

I managed an average cycling speed over the entire distance of 17.1 mph (27.5 kph). I did this maintaining an average heart rate (142 beats per minute [bpm]) that is 74% of my maximum heart rate (192 bpm). The route I took involved 6635 feet (2022 metres) of ascent. And, courtesy of the algorithm built into my Garmin GPS, I apparently burned around 5000 calories (kcal) while cycling. That’s the equivalent energy of 10 Big Macs!

And, as alluded to before, I consumed just two energy gels, both on the Le Havre-Paris leg. One in the morning and one in the afternoon. I had two eggs, coffee and orange juice on the ferry for breakfast before starting the French leg, and I ate a smoked salmon and salad lunch at the halfway point in Évreux. Starchy carbs didn’t feature. I measured my body fat on a Tanita body composition scale before leaving and it stood at 11.5%. On my return it was 7.5%. Yes, n might equal 1, but you can’t function fully as I did at the end of a 200-mile ride on the food I had consumed without relying on the burning of fat and ketone bodies.

An unexpected surprise: low carb lunch in Évreux and reprieve from driving rain and wind

A note on fat-burning

Fat-burning, not by accident, allows us to extract over twice the amount of energy per gram of fuel than when we burn carbs or protein. When we over-indulge in simple carbs, there’s no need for us to dig deep into our own fat reserves. Our blood is rich in glucose, the dirty-burning fuel our body uses when we are reliant on sugars and carbs as our primary fuel.

This remarkably flexible system for metabolising fuels allowed our Palaeolithic ancestors to function in unpredictable cycles of activity, aimed at hunting and gathering food, a process that sometimes lasted days, followed by feasting and rest. No one is suggesting we return to our caveman ways, but our genetic make-up differs very little from those of our ancestors some 20,000 years ago. Agriculture only began circa 12,500 years ago and it was only then that the predecessors of wheat, such as emmer, einkorn and spelt, and later, other cereals including barley, maize and rice, became staples in most parts of the world.

Puncture repair in the rain

While many of us tax our carb-burning glycolytic metabolism to the full these days, our ancestral fat-burning pathway that relies on the beta-oxidation of fats often remains largely dormant. To stave off sugar crashes, many of us become ever-more reliant on carbs, and more particularly simple, rapidly metabolised starchy carbs and sugars, as our fuels. It’s no accident that what we don’t end up burning as glucose or glycogen gets converted into fat. It’s part of our survival mechanism. It gives us fuel for later use. To hunt down that sabre-tooth tiger – or, in my case, to cycle to Paris on a minimum of additional fuel.

When we forfeit a clean-burning fat metabolism for the dirtier burning of carbs, we also produce many more free radicals that in turn have the potential to damage tissues, membranes and DNA — effectively ageing us more quickly.

Less than 1 km later this track into the Parc naturel régional du Vexin français became unrideable and I had to retrace my route and find another way to Paris

Switch on your fat-burning metabolism this summer

We can all do it. Some do it easier and quicker than others. For most of us, it’s around a 12 week journey, but it’s not arduous. In fact, there are ways of making it easy, hugely rewarding and even fun!

From a dietary perspective, we suggest you follow the nutrient composition and guidelines in the ANH Food4Health plate.

Keto-adaptation principles

- Eat two meals daily, not three - Half your food will be unprocessed vegetables and small amounts of fruits with high quality protein and healthy fat sources. You would be using a relatively low carb diet, or at least one minimising or free of starchy carbs, such as the ANH Food4health plate

- No snacking in-between meals, you will need to leave at least 5-hour intervals between your meals

- Each week, engage in two 16+ hour fasts (don’t panic, you’ll be asleep for about half of that time) and then engage in 20-30 minutes of High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) (see ‘Your training plan’ below).

- Add some supplementary nutrition from some good quality botanical-rich food supplements, including antioxidants, to support your metabolism and recovery

- Avoid gels and carb- or sugar-based drinks while you’re riding

- Consume 20-25 g of high quality, undenatured protein within 30 minutes of completing any intense or extended physical activity to support muscle growth and recovery. Pea protein isolate as a food supplement is ideal as it’s highly digestible, hypoallergenic and suitable for vegans and vegetarians.

As your metabolism becomes more flexible, you’ll be able to adjust your regime to your needs. The rewards are such that you won’t be inclined to revert to your old dietary and lifestyle patterns!

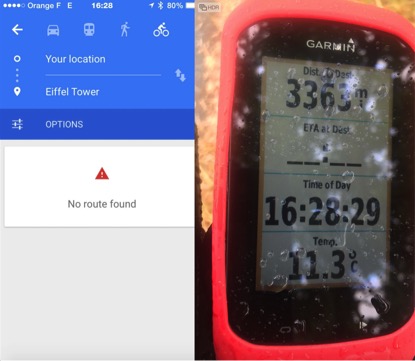

Technology failure: When your iPhone says it can’t find the route (left) and your Garmin says there’s 3363 miles to your destination (right), it’s okay to say you’re lost

Your training plan (for cyclists)

- Two long-rides per week (non-fast days). For me one of these is typically a ride to work and back (25 miles [40 km] each way). Another tends to be at the weekend if I’m not working. These training rides shouldn’t be on consecutive days, that’s why so-called ‘weekend warriors’ sometimes fail to make progress in their performance despite their big efforts two days a week. Many people find the easiest way of doing these longer training rides is early in the morning, when our cortisol hormone is elevated.

These training (or cycle to work!) rides should be over 2 hours in duration with at least one that’s over 3 hours each week. That’s because it takes around 1 to 2 hours to burn off stored muscle and liver glycogen (the storage form of glucose).

- Fit in two to three sessions of High Intensity Interval Training (HIIT) per week. It’s a great way to use the right fuel after one of your 16 hour fasts. You can do this on a turbo trainer, or combine gentle riding during recovery periods, along with intense sprints for your high-intensity intervals.

As you ride in your fasted state, without the rich supply of blood sugar, your body will re-learn that it has to beta-oxidise fats. It will start to generate a very low level of ketone bodies that your body and even your brain can use as fuel. It won’t happen immediately and it might take two or even three months before ‘nutritional ketosis’ kicks in.

If you’re so inclined you can even use a ketone meter such as the Ketonix to measure ketone bodies. It’s something endurance athletes, especially the pros, are doing more and more often as they learn to appreciate the remarkable benefits of keto-adaptation.

As you go through the process, you need to minimise (or eliminate) your starchy carbohydrate intake. We often think of this as a ‘low-carb diet’, but many forget that, using the ANH Food4Health plate as a guideline, the body still receives ample complex carbs from veg, and to a lesser extent fruit.

Two races in one: 23 hours and 58 mins after leaving my home. At the Arc de Triomphe, cleared by terrorist-aware, twitchy French police, with the screens behind me telecasting the crowning of Chris Froome further down the Champs-Élysées, winner of the General Classification of the 2015 Tour de France

The Bottom line

Some people ask: why go to the trouble? My answer is simple: it is no trouble. It’s about becoming healthier, being less of a burden on society as you age, having a greater quality of life, being able to adventure. The approach combines a relatively low carb, moderately high protein and healthy fat diet, with intermittent fasting and physical activity, some of it in a fasted state.

When I started my journey into keto-adaptation, I always would carry a gel in the back of my jersey in case I needed to use it. It reassured me that I wouldn’t be left behind if I felt the ‘bonk’. After 2 months, I didn’t need it any more for rides of 60 miles (100 km) or less. These days when I do need a gel on long, endurance rides, I need way fewer than those who haven’t keto-adapted.

As with so many health regimens and treatments, there was a side effect: I lost 25 kg in weight in 6 months and my cycling performance stats sky-rocketed! At 55, I’m riding faster and longer than ever before, and with much less stress on my body.

A number of friends have decided to join me next year: so next time I won’t have to battle the elements on my own (you can save around 40% energy expenditure through reduced wind resistance by drafting behind another rider) – and we’re going to cycle the return trip which this year was undertaken by rail on the Eurostar!

Comments

your voice counts

30 July 2015 at 3:54 pm

Inspiring stuff Rob and of course fascinating in the way you've walked the walk - or perhaps ridden the ride.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences