Content Sections

"The world doesn't need more smart doctors, it needs more warm and wise doctors. Be thewisdom yourself — be the warmth yourself, and be the doctor that the doctors have forgotten to be, for it is time to save medicine, to save humanity."―Abhijit Naskar (neuroscientist), Time to Save Medicine (2018)

By Robert Verkerk PhD

Founder, Alliance for Natural Health

Executive & scientific director, ANH-Intl and ANH-USA

Few of us will not have experienced, witnessed or heard of one or more deeply disturbing travesties of medical ethics over the last three years. We wrote a feature about some of these issues last week.

Perhaps you're aware of breaches of respect for the autonomy or privacy of individuals? Or the failure of health authorities or vaccination centres to offer the public properly informed consent? While mandates were far from universal around the world, many of us were acutely aware of the manner by which coercive consent to medical procedures was achieved in the absence of pertinent information that would likely have greatly changed public perception of the risk/benefit profile that we discovered was well known to, yet not publicly shared by, product manufacturers, regulators and health authorities. Those who refused to consent often faced discrimination, including loss of livelihood.

These jaw-dropping breaches of ethics make it incumbent on us, as it did to our forebears in the wake of the Holocaust, to re-imagine the moral compass we use to guide our journeys as we seek health, resilience and wellbeing. Perhaps we feel compelled to re-evaluate ethics around healthcare, less for ourselves, more for future generations.

Dear friend, Croatian-born, coordinator of the Global Covid Summit, US (Texas-based) family physician, Dr Katarina Lindley felt such inspiration. During Dr Lindley and my regular collaboration on matters bioethical during the height of the covid-19 crisis (2020-22), I was grateful to be asked to provide input to her wonderful, 13-point Oath of a Medicus, applicable specifically to medical doctors. All of the points, and more, of Dr Lindley's Oath of a Medicus are accounted for in our overall framework. However, our present work, which has been the central pillar of Paraschiva's work with us as Mission Facilitator since she joined the ANH-Intl a few weeks ago, includes a lot more context and clarification around each point, including background explanation. As is so often the case in bioethics, the devil is in the detail — and the interpretation!

>>> Download ANH's full report on The Therapeutic Relationship (Pillar 1). Health and Ethics: A New Framework (2023). Principal authors: Verkerk R, Florescu P. Alliance for Natural Health International.

>>> Download ANH's full report on The Therapeutic Relationship (Pillar 1). Health and Ethics: A New Framework (2023). Principal authors: Verkerk R, Florescu P. Alliance for Natural Health International.

Why medical ethics must be reframed

Today the World Health Organization (WHO) announced the end of the state of emergency for COVID-19. Sadly, that won't mean we are able to revert to our pre-2020 ways. Far from it. Much of the architecture and process that removes autonomy from individuals and hands it to the state, will remain in place. Think of the model they're working with more as a staircase; each new crisis taking us ever closer to an Orwellian place of control of the many, by the few.

These aren't the only reasons we can't afford to put ethics as applied to our health on the back burner. There are at least two other big reasons.

One is the rapid transition towards a centralisation and globalisation of political power. In public health terms, this means that the unaccountable, unelected, largely privately funded WHO will be expected to sit at the head of the top table. The proposed amendments to the International Health Regulations (2005) that are currently in negotiation (more on this next week) will try to see to that. With no pushback, this will greatly impact the ways in which fellow humans who remain tethered to the machinations of the state will be expected to manage their health. Without a concerted effort to buck the current trend towards global control of public health, core principles of civil liberty such the rights to privacy, self-determination and freedom, as well as the principle of autonomy, accepted as a cornerstone of medical ethics, will all be kicked deep into the long grass?

The second reason relates to the scale of the unprecedented, institutionalised misinformation and psychological manipulation of the public that has accompanied the myopic approach to dealing with a pandemic that was almost certainly triggered by gain-of-function research. Central to this has been the widescale deployment of experimental synthetic biology based, prophylactic medications that turn our bodies into drug factories. The mRNA and adenoviral vector vaccine platforms have been introduced in a climate in which governments and health authorities peddled fear and propaganda deliberately in order to ensure a compliant, submissive public.

>>> Read Dr Christian Buckland's open letter to Rishi Sunak about how the UK Government failed its public

In a world in which scientific dissent has been quashed and social media companies have become the enforcers of permitted public speech, the majority remain largely unaware of the magnitude of change that came with the mass introduction of mRNA and adenonoviral technologies. These technologies have effectively been 'normalised' under at least partially orchestrated, highly abnormal conditions. Yet they are so fundamentally different to the medications and vaccines that came before them, it is not at all beyond the bounds of possibility that these gene-based technologies could contribute to an untoward, evolutionary bifurcation.

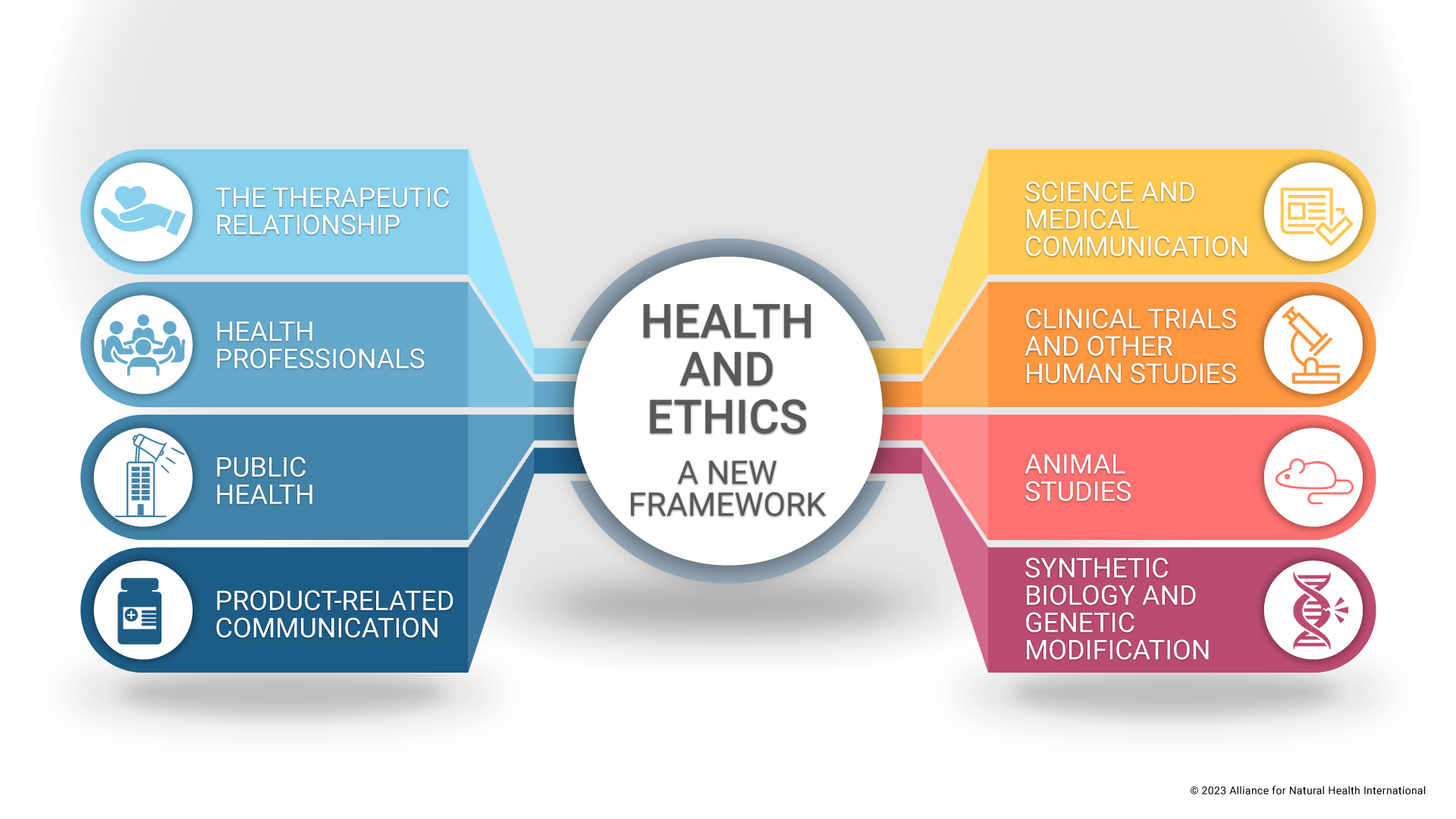

These are among the disturbing and unique circumstances that triggered our work in building a new framework for health and ethics, suitable for our current era. The framework has 8 pillars, and today, we are delighted to be able to release the first pillar, concerning the all-important relationship between a health practitioner and his or her patient or client.

Extracts from the report

The 12 Propositions

- Autonomy. I shall respect the autonomy of each and every individual in my care by fully acknowledging his or her right to self-determination as well as the individuals’ needs and preferences. This requires that I shall guide, rather than dictate, whilst allowing those in my care the freedom to make informed choices free from undue influence.

- Informed consent. I will seek the informed consent of the individual before taking or recommending any action that might influence the health of an individual in my care. I will facilitate the individual’s holistic understanding of the issues at stake, as well as an environment conducive to shared decision-making. I will communicate relevant, unbiased information on all available options, including the most likely consequences of the various options, in ways that are clearly understood. If the patient or client does not have capacity to consent according to the prescribed guidelines for assessing capacity, I shall ensure that the consent is given by an appointed decision maker or person who has responsibility for the individual. Only in emergencies, and where there is no capacity and no responsible person available, shall I proceed with the treatment that I believe, according to my professional knowledge and experience, to be in the best interests of the individual. Thereafter, and as soon as reasonably possible, I will endeavour to seek consent, directly or indirectly, depending on capacity, for any additional actions that might influence the individual’s health.

- Non-maleficence (‘avoiding harm'). I will use my best endeavors to adhere to the bioethical principle of non-maleficence by ensuring that any actions taken, decisions made, or recommendations given while under my care, avoid, prevent or minimise harm to the individual. This requires that the relevant and available options are sufficiently weighed up and considered within the context of a therapeutic relationship built on trust and respect, which includes shared decision-making. I will keep the interests and welfare of the individual at the heart of all my actions, decisions and guidance, while taking any precautions that help to avoid, prevent or minimise the potential for harm.

- Beneficence (‘doing good’). I will be diligent in my application of my knowledge, skills, experience and attributes, in ways that aim to optimise the health, welfare and quality of life of the individuals in my care. I shall also be diligent in refreshing and advancing my professional knowledge and skills to this effect. I shall be respectful, kind, thoughtful, caring and compassionate in all my dealings with the individuals in my care. I will regard the relationship as one of partnership.

- Fairness and justice. I will act in accordance with the bioethical principles of fairness and justice by ensuring that, throughout my professional life, and as far as is reasonably possible, I will respect the right of all individuals to health and healthcare, while treating others as equals and also treating them equally. In apportioning justice, I will take due account of the needs and capacities of the community and environment surrounding the individuals in my care.

- Unconflicted practice. I will place my client or patient’s interests at the heart of all my actions associated with the therapeutic role. I will endeavor, within the limits of my professional training, skills and clinical experience, to ensure that each client or patient receives qualitative and quantitative medical service of the highest order. I will never take advantage of any client or patient in order to further my own personal, financial or other interests, or any interest of any third party, be it an organisation, company, institution, authority, or government.

- Integrity and accountability. I shall be accountable and act with integrity, both professionally and personally, in each and every relationship with my clients or patients, regardless of circumstances or challenges I face. This includes being straightforward and honest, while doing my best to display consistency in my practice. I will ensure coherence between principle and action. Furthermore, I will avoid compromising my professional judgments because of bias, conflicts of interests, or the undue influence of others.

- Openness and transparency. I shall promote transparency by always telling the truth not just through my words, but through my thoughts and actions. I understand the importance of building and maintaining trust in the relationship with each of my patients or clients. I will ascertain whether each does or does not want to know specific information, such as a diagnosis or prognosis, and I will always act in accordance with their wishes, assuming these are aligned with those and other general principles of bioethics. I will always disclose any errors that may, or have, affected my clients or patients, and I will never withhold or omit any information that I am aware or sense that the patient or client would wish to know. I will not hesitate to seek counsel from, or refer to, other health practitioners where it is clear this would be in the best interests of the health or welfare of my patients or clients.

- Privacy and confidentiality. I will respect my patient or client’s privacy and not divulge any personal information outside the scope of the consultation, other than in exceptional circumstances, where maintaining confidentiality would put the patient or client or another at great risk of harm. I will ensure that the patient or client has full access and ownership of his or her health-related data, as well as the right to determine how, when, and for how long, specific health data are to be shared with any other health practitioners or third parties.

- Non-discrimination. I will not discriminate on the basis of age, gender, sexual orientation, heritage, nationality, genetics, background, religion, beliefs, disability or ability, political affiliation, social standing, or any other characteristic. Neither will I violate the fundamental rights or civil liberties of those in my care. I will treat all my patients and clients with compassion and offer them the same, high standard of care. I will also honour the diversity and authenticity of those for whom I care.

- Respect for the dignity of all life and natural systems. I will respect the dignity and inherent worth of nature and all living beings. This may extend to my recognition of a spiritual dimension to humans, possibly as well as to other living beings. I recognise the interactions between living beings, regardless of their form or size, as well as their role in helping my patients or clients regenerate or balance the many processes that give rise to health, resilience and I will listen actively to my patients or clients in order to understand each of their opinions, belief systems, needs, desires and preferences, all of which I will respect through my commitment to support their healing.

- Reciprocity in human relationships. I shall undertake to take full responsibility for the care of my own health; physically, psychologically, emotionally and spiritually. I will be mindful of my own limitations in my self-care, and, where and when required, I will ensure that I seek the support or counsel of others. I recognise the principle of reciprocity in therapeutic relationships, and that my ability to assist my patients or clients will be compromised if I have not made the management of my own health and welfare a priority in my life.

Discussion

Codes of ethics are instruments that should not be static. Instead, they should be flexible and adaptable, meeting the needs of an ever-changing world. Komparic and colleagues (2023) argue that they are “living, socio‐historically situated documents that comprise a mix of prescriptive and aspirational content”. These codes build on principles that have been found to be relevant consistently through the ages, from the most ancient texts through to the contemporary era. While society is dynamic, moral principles that determine what is right or wrong, good or bad, fair or unfair, tend to remain consistent as they reflect the essence of what is at the heart of being human.

Widely publicised breaches of well-recognised principles of medical ethics have been particularly common since the COVID-19 pandemic was announced in early 2020. Such breaches include the common failure to exercise informed consent in the absence of coercion, and the withholding of early treatment protocols that were requested by patients with severe COVID-19 disease and which had been demonstrated to be beneficial with minimal risk of collateral harm. The latter breach was aggravated by widespread pressure from health authorities which threatened to strip physicians of their medical licenses if they deviated from the narrow confines of recommendations that were strongly influenced by vested interests.

This first pillar of ANH’s new framework outlines 12 principles and propositions for health practitioners, applicable to their relationship with those who they support or are in their care. This pillar builds on the four principles initially outlined by Beauchamp and Childress in 1979, namely, autonomy, beneficence, non-maleficence and justice.

However, in the current era, one in which the moral compass that has long guided our approach to managing human health appears to have been cast aside, these principles are no longer sufficient. This is especially the case if we are to make a determined effort to re-invigorate the connection and the 'light' that can be generated between two humans and the world around us, the two most durable and effective healing relationships we know of on our planet.

We need to extend beyond a simple code of conduct for how practitioners interact with their patients or clients. As great physicians and philosophers from the past emphasised, medical practice should also take into account those virtues and elements of character that have long been associated with consistently impressive healing – a notion that we might today refer to, somewhat blandly, as ‘best practice’. Such practitioners consistently uphold traits or values such as trustworthiness, self-discipline and ‘humanness’ (Tsai, 1999).

In the current code, a differentiation is made between a “principle” and a “proposition”. Principles here are generalised and seek to outline the intended objective. The “proposition” translates this principle into a vow or undertaking, which can be agreed by health practitioners who align with the code. The proposition also aims to provide an interpretation of the principle that reduces ambiguity and is practicable. Agreements may be informal, or they may be formalised by clinics, other health systems or practitioner associations.

Medical ethics has its roots in ancient traditions that committed their ethical values to the written word. Particularly prominent were the writings of ancient Greek physicians and philosophers, as well as the ancient texts of Ayurveda and traditional Chinese medicine.

Some of these same principles, such as the sanctity of nature and other life forms, are also prevalent in many indigenous cultures and have been passed down through generations. In Aboriginal cultures, the longest known living culture “in country humans and nature, and nature and culture, are not regarded as separate, but are entangled together in all types of relationships” (Weir, 2012). Based on her many years of work learning to understand the connection between Aboriginal people and the land (nature), the late anthropologist Debbie Bird Rose wrote that humans and all of nature exist as ecological systems composed of conscious beings who communicate, act and react, and “adhere as a matter of self-interest and free will to the same set of understandings” (Rose, 1992).

During the course of Western history, various moral theories were adopted by philosophers, reflecting perspectives that were of their time and place. For instance, JS Mill argued that utilitarianism was the route to happiness and the fulfilment of society as a whole. Kant, by contrast, proposed deontology, which seeks to apply the same rules to everyone regardless of the outcome through its “supreme principle[s] of morality” (Amer, 2019).

In practice, these theories have often led to conflicting solutions to moral dilemmas. This code attempts to bring together all of the key principles pertinent to the therapeutic relationship, drawing elements from the ancients, while seeking to provide a coherent, straightforward compass to help guide the approach, behaviours, values and virtues that history tells us will optimise the dyadic relationship between health practitioners and their patients or clients.

Modern, Western medical practice claims to hold autonomy at its heart, with the patient being at the centre of decision making. The fourth of the seven principles of the Constitution of England’s National Health Service (NHS) states: “[The NHS] should support individuals to promote and manage their own health. NHS services must reflect, and should be coordinated around and tailored to, the needs and preferences of patients, their families and their carers.”

Unfortunately, this key principle is often disregarded in contemporary mainstream medical practice. In its place, you will still commonly find the more paternalistic approach of old, where doctors make decisions on behalf of their patients (acting as ‘gods’ not ‘guides'). Worse than that, you will also find many instances where the views of health authorities, these often heavily influenced by pharmaceutical interests, become the prime determinants of the medical approach. Another increasingly common trait of mainstream medical practice is disconnection — disconnection between people and from nature — a trend that can be accentuated by modern, ‘disconnected’ lifestyles and increasing reliance on technology, including digital systems and remote consultations.

There is an urgent need to reframe the ethical framework around medical practice. Effective, safe and sustainable clinical practice must recognise fundamental human rights, the intrinsic free will of living beings, the significance of our connection with other humans and our natural environment, a non-physical or spiritual dimension, and the importance of the relationship or interaction between the health practitioner and the patient or client.

Through a respect of the human right to self-determination, the practitioner should act as ‘guide’ not ‘god’, in the reciprocal, albeit partially asymmetric relationship in which improved health and, often a fee, is traded for knowledge, expertise and skills, as well other values and virtues of character. Information and guidance from the practitioner helps the patient or client to make an informed decision, one aligned with his or her particular views, values and preferences.

The present code of ethics is respectful of an individual’s inherent spiritual nature and the sense of connection to a higher source. As Seetharam (2013) suggests, ethics in medical practice should not just be a code of conduct, but also a “spiritual imperative”. Modern codes of medical ethics have typically lost their “divine character” (Kalokairinou, 2011) and this code attempts to redress this imbalance, while endeavouring to make it both culturally and modality agnostic.

>>> See full report for references.

>>> Visit covidzone.org for our complete curated covid content of the coronavirus crisis

>>> If you’re not already signed up for the ANH International weekly newsletter, sign up for free now using the SUBSCRIBE button at the top of our website – or better still – become a Pathfinder member and join the ANH-Intl tribe to enjoy benefits unique to our members.

>> Feel free to republish - just follow our Alliance for Natural Health International Re-publishing Guidelines

>>> Return to ANH International homepage

Comments

your voice counts

There are currently no comments on this post.

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences