Content Sections

By Rob Verkerk PhD, founder, scientific and executive director

Regardless of how you feel about the threat posed to the human race by the new coronavirus, or the human response to it, these last 10 months have been an ordeal. You may or may not agree that the best thing we could have done was to try to reduce transmission of a virus that is innocuous to the vast majority and in the process drive a wrecking ball into economies and livelihoods. Equally, you may or may not agree that developing synthetic biology vaccines at warp speed is the only way out of this. Regardless, barring the few that have benefited massively from the pandemic, nearly all of the rest of us have been impacted negatively – sometimes catastrophically so. Years of work to build employment and narrow socio-economic inequalities has been undone.

As they say, there’s no point crying over spilled milk. Let’s try and get it as right as we can going forward, with as much learning as we can muster under our belts. Despite what’s happened, there is always a silver lining somewhere. If we lose focus of this and concentrate only on the negativity, we will pay an unnecessarily heavy price and among the many outcomes will be anxiety, depression, apathy, disempowerment. That and more costs lives and people’s futures.

So, in my last blog of the year, I wanted touch on what I feel are some of the most important things we’ve learned about the anthropocentric world we inhabit that we are so drastically, and often unwittingly, reshaping.

Pasteurian pursuit

Louis Pasteur’s germ theory has been re-popularised. Prior to widespread recognition of SARS-CoV-2 in early 2020, there had been a trend for microbiologists to be at least as interested in the ‘terrain’ that would trigger pathogenicity in otherwise latent microorganisms, as in the pathogens themselves. All this work suddenly seemed irrelevant once the coronavirus arrived on the scene. It was all about the virus, that was fully sequenced in early January. Within days came the WHO-approved antigen test led by Dr Christian Drosten’s group at Charité University Hospital in Berlin, now a focus of legal action.

The silver lining to this Pasteurian pursuit has been the belated but by now widespread recognition of the importance of the terrain, especially vitamin D and C, as well as zinc status. These micronutrients help to provide the immune system with resources that are often inadequate for its competent function. We’ve launched campaigns around both vitamins (links to our vitamin D and C campaigns are here and here, respectively). We’ve also recommended use of science-based levels that are much higher than those recommended by governments that have failed, with very few exceptions (e.g. folate and neural tube defects), to acknowledge the preventative or therapeutic role of supplements.

French biologist Louis Pasteur (1822-1895)

Early next year, we will be releasing the results of the work we’ve commissioned at a university in the Netherlands that aims to counter the restrictions being imposed by national authorities in Europe. The output will be an open source risk/benefit assessment tool for micronutrients in supplements that we believe will help democratise the agreement on beneficial, safe and proportionate maximum levels for food/dietary supplements.

Conflation of science and politics

Another observation that struck me as a scientist (who first qualified in the discipline 39 years ago) is the engagement of politicians and world leaders in scientific decision making. The circumstances that allowed this to happen involved three main factors: a) the emergence of a global crisis that transgressed borders, b) one that posed a significant health threat, and, c) ongoing and great uncertainty over the actual threat posed by the virus, as well as how it might be best contained, delayed, mitigated or prevented.

So while scientists have been feeding huge amounts of information to governments and inter-governmental organisations like the World Health Organization (WHO), it is governments that have been making the decisions and policies that most affect our daily lives. These circumstances have allowed for remarkable U-turns in policy on lockdowns and other restrictions. They have also resulted in a communication of a lot of erroneous information to the public, such as telling people they should stay indoors, or justifying huge public spending programmes for mass testing using PCR on the grounds of its infallibility. When a government exerts so much control over how we should manage a single pathogen, everyone looks to that government for answers. When governments don't seem to have a full handle on things, even ex-leaders, like former British PM Tony Blair, decide to chime in and tell everyone how vaccines should be rolled out.

Right now, while scientists in the UK attempt to understand the transmission capacity, virulence and host preferences of the two new "mutant strains" of SARS-CoV-2, politicians are forced to give answers. Expect some to be wrong.

When we live in a world where distrust of big government and big corporations has reached an all-time high, this isn’t a good plan. Better to communicate truthfully about the uncertainty and substitute uncertain information for something that appears like, but isn’t, fact.

As Agamemnon was reputed to say: “There is no avoidance in delay.” Back to the mutant strains of SARS-CoV-2, if there is no evidence suggesting increased threat to public health, there is no justification to act as if there was. So don’t shut the borders. Let nature do its thing. This brings us swiftly to the next point.

Abuse of molecular biology

Those who have said that a new virus might not even exist, have perhaps not looked at the huge scientific efforts that have been expended in the field of molecular biology. One argument we’ve heard many times is that the virus has not fulfilled the 4 original Koch-Henle postulates, proposed in 1884 for bacterial, not viral, infections, that have been viewed by some as the necessary proof of causation of Covid-19. Actually, if you accept the modification for these postulates in 1937 by Thomas Rivers for viruses that are not amenable to culture, the revised 6 postulates have been met many times over, as they were for SARS before it. The use of molecular biology technologies like RT-PCR has been central to this in the identification of the virus as contrasted with diagnosis of disease (see below).

When the first wave of infection hit Europe, then the USA and South America, it was immediately apparent that only a small sub-group of the population were impacted, primarily those with multiple underlying conditions or those who were very old.

When the WHO said in March “test, test, test”, the largest roll-out of diagnostic testing the world has ever seen was begun. Then it seemed that the business model driving this boom overtook logic and science. Critically important elements such as Bayes’ theorem that has long informed us that false positives will become very common when prevalence is low, set the scene for a pandemic that might never have an end. Dissenting scientific voices such as those of Dr Carl Heneghan at the Centre for Evidence-Based Medicine at Oxford University were marginalised or ignored.

The pandemic was soon flipped into a ‘casedemic’. The very life-saving molecular biology tools that had so effectively and rapidly sequenced this virus, as well as many others before it, were transferred to mass testing programmes, only to be misused and abused at an incredible scale.

Clear flaws in how the tests were being used as well as their interpretation were identified and are now the subject of a petition to the European Medicines Agency.

The WHO then belatedly indicated its recognition that over-amplification by RT-PCR would deliver false positives for fragments of SARS-CoV-2 (and possibly other viruses sharing the same gene sequences being amplified) with no potential to cause infection. It has still done nothing to cap the cycles threshold of the PCR devices.

Now gene sequencing is delivering a new type of narrative – one of mutant viruses. The reality is that all viruses mutate and in the case of RNA viruses like this the mutations rarely lead to changes in function or pathogenicity. Many thousands of mutations have occurred already, but the latest mutants to be found in the UK involve significant changes to the gene sequence of the spike protein. Accordingly they could affect different aspects of the interaction with the host, including transmission, immune response, and so on. Presently there is scientific debate over whether transmission is increased and if human hosts include people of younger age. The general view is there is, as yet, no evidence of increased virulence. There may also be impacts on vaccine effectiveness, given we know that some mutations can be resistant to neutralising antibodies; but this is currently being widely denied (without supporting data) by vaccine makers.

All of this deep uncertainty won’t become less opaque until extensive gene sequencing and proteomics have been integrated with epidemiology from different countries and regions. That’s something that takes time. But knee-jerking to the new mutations given there is no evidence yet of any increased threat to life seems unjustified, despite the murky and premature status of the science.

The silver-lining to all of this could be that we learn just how much unnecessary damage can result from the misuse of molecular biology. Let’s use this technology judiciously and cautiously. Just like my last point, this one takes us neatly to the next.

Cronyism

‘Jobs for their mates’ has been a feature of the pandemic, none quite so clearly illustrated as in the UK by Sophie Hill’s My Little Crony interactive map. We appreciate that tender times have been limited and urgency high, but this is public money we’re talking about.

We are thrilled to see the likes of the Good Law Project taking a legal scalpel to the problem– hopefully delivering results and teaching our leaders that cronyism, which is separated from corruption only by a fine line, is unacceptable.

Last stop café

It is challenging to find any substantive evidence that the new generation of synthetic biology vaccines can rid the world of this virus. They depend on new synthetic biology vaccine platforms that are untested at scale. The effectiveness claims from Phase 3 trials on which emergency authorisation of the BioNTech/Pfizer and Moderna vaccines have been based rely on very small groups of individuals, not reflective of the population groups at most risk from the virus. Additionally, we have the curved ball of the recently exposed significant mutations to the spike protein to add to the list of uncertainties.

Vaccines for the two most closely related coronaviruses, SARS and MERS, caused excessively severe reactions or arrived too late. These viruses have managed to self-regulate with the immune system of their human hosts so they’re still present but no longer a global threat. SARS-CoV-2 could peter out in the same way, or probably more likely, weaken in virulence over time and become endemic as part of the pool of circulating respiratory viruses. No wonder Roche has rolled out a ‘3 in 1’ antigen test kit that detects SARS-CoV-2 as well as influenza A and B viruses. A complementary ‘3 in 1’ winter vaccine must be on someone's drawing board.

We’d argue, as we did at the start of the pandemic, for those of use who are healthy, we should stop either trying to fight with, or hide from, this virus. Nature will take its course and will re-balance. It turns out the patterns of mortality in Sweden and the UK over the last year have been remarkably similar – yet the governmental responses have been dramatically different. It seems the virus is in charge more than humans, although time will ultimately tell. It may be that in time we will see that the inordinate efforts invested in trying to control the virus resulted in vast amounts of resources being wasted. As well as driving a coach and horses through decades of societal efforts to narrow social and health inequalities. Using lockdowns and social distancing to slow transmission of viruses might one day be considered akin to trying to herd cats.

What we have to do is be much more cognisant of whole systems – and therefore the risks and benefits to all parts of the human and non-human ecosystems we inhabit and share.

We need to do this in a way that minimises net damage, which is why we can no longer ignore the collateral damage caused by efforts, such as lockdowns and related measures, to delay transmission. We also probably need all the available data – which is why the vaccine transparency initiative we’ve launched is so crucial in our minds.

We need, too, to get real about it being unlikely that there will ever be a single silver bullet for this virus, even one that comes in the form of a syringe. And finally, we should appreciate that we probably could not afford to repeat this exercise every time we encounter a new virus that has adapted to our species.

Governance and censorship

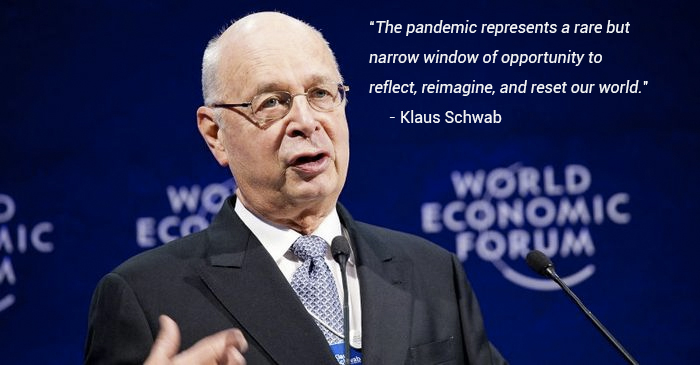

A global pandemic, even one that had to be massaged from time to time to ensure a suitable level of fear and hysteria was maintained in the minds of the masses, has been the ticket for a number of very fundamental changes to the way we are governed. The pandemic control system, that had been rehearsed for such an occasion, meant that global governance of the pandemic response, coordinated by the WHO, was able to be rapidly initiated in January 2020. The World Economic Forum was also closely involved, given its close association with stakeholders, including the media and vaccine makers.

Superimposed with the transition to increasingly authoritarian approaches to controlling the spread of the virus were the complex issues around the recognition of racial inequalities triggered by the killing of George Floyd, the US election, and Brexit. Division and polarisation of viewpoints arose like a fountain from the desert during the course of the year, beyond most expectations. Social media platforms, especially, have gone to extraordinary efforts to curtail freedom of expression. Even mainstream media channels like the BBC, once hailed for its balanced reporting, has been roundly criticised for its biases (here and here).

The transitions proposed by the World Economic Forum are so material to our everyday lives, to how we work, get paid, eat, recreate, manage our health and interface with one another and the world around us, that it may turn out to be a grave mistake to try to rush them through while most of the democratic functions of the Western world have been suspended owing to the perceived, ongoing emergency.

The World Economic Forum has described the covid-19 pandemic as a “once-in-a-lifetime opportunity”, an opportunity to make fundamental changes to the social and geopolitical order, as well as to how cyber technologies can be interfaced with humanity. The World Economic Forum calls it the Great Reset, which has been intimately linked to covid-19 through the co-authorship of a book by the Forum’s founder, Klaus Schwab. The Great Reset, that can be likened to pressing the reset button on planet Earth, is the chosen gateway for the ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’, the subject of another Schwab book. One that envisions a blurring between technology and humans, including the development of transhuman beings replete with synthetic genes. We debated the ethics of genetically modified foods for decades, why now is there no public debate on synthetic biology vaccines, implantable cell phones or transhumans?

With this kind of backdrop and the suspension of normal social and scientific discourse, forcing people into social contracts when they have so little say in, or even knowledge of, the content or implications of the contract, is a very risky endeavour. One that could lead to massive social unrest. Better to re-instigate due democratic process and scientific discourse and co-create a new way forward for people, industry and society. One that resonates with protecting our delicate and besieged planet, yes.

But one that also resonates with the masses, not just the few who have been sampling the rarefied air of Davos each January.

Bifurcation

I want to finish my year-end blog with what I feel is the single most important take-home from the year. Irrespective of which side of the highly polarised debate around covid-19 responses, governance, media censorship, cyber technology, surveillance, or democracy (let me stop there) you sit, 2020 will almost certainly be seen as a highly significant fork, or bifurcation, in human evolution. It may be as relevant as the transition that occurred in Abu Hureyra in present day Syria, some 10,000 years ago. This settlement, that existed up until around 6,000 years ago, represented the transition from nomadic to pastoral lifestyles. Archaeologists and anthropologists have pieced together from this settlement the first evidence of widescale domestication of plants and animals. Abu Hureyra set the scene for the bifurcations we now regard as the agricultural and industrial revolutions.

At this point, in recognising the extreme significance of the present time, we might find ourselves on the same page as Klaus Schwab. Where we, or at least I, differ, is that you shouldn’t be predetermining the future of the human race without consultation with most of the nearly 8 billion people with which you share the planet. And you shouldn’t try to force such great transition through while so many of the civilised processes associated with advanced democracies have been suspended.

In a recent article, Hungarian scientist and philosopher, Ervin László pondered over the role of covid-19 in such a bifurcation event. He wrote the following:

“We have learned a few things about such a shift. It is one-way, it cannot be reversed. But it is not predetermined - it allows choice. In a bifurcation, we can choose the way we go. For the first time in history, we can consciously and purposefully choose our destiny. This could be a bright destiny; the dawn of a new era of sanity and flourishing. But whether it will be that is not determined. It is up to us.”

- Ervin László, Paradigm Explorer, 2020, 122, 4-5.

Here’s hoping László is right. His call is at least hopeful, and where there is hope, anything is possible.

That’s why we will be working just as hard in 2021 to help bring more and more people on board with a vision and plan for humanity and health that works with, not against, nature.

In health and hope, here’s wishing you the very best for the New Year.

More information

>>> For a full repository of ANH-Intl articles and video on covid-19, visit our Covid - Adapt Don’t’ Fight campaign page.

>>> Sign up here for our free Heartbeat newsletter.

>>> We are 100% donation funded, please consider offering an end of year donation to support our work, so we can continue helping to protect and promote natural and sustainable health into 2021. Thank you.

Comments

your voice counts

24 December 2020 at 12:12 pm

Thanks for the succinct overview, yes I seriously believe 2021 can mark a start of a new epoch when mankind begins to learn we are all part of this unique soup of living stuff we call our planet Earth. We must all learn how to change our lives to give future generations a chance of surviving and enjoying the wonders on this speck of life supporting rock.

28 December 2020 at 12:15 pm

Thanks, Michael. Yes, the disruption of 2020 has set the scene for big changes in 2021, and as long as we don't let the politicians run the show in isolation, there is still much live for. There is very good reason for us all to do what we can to co-create a world that is more compassionate, connected, respectful and hopeful than the one we left behind in 2019! Wishing you the best for the New Year.

25 December 2020 at 4:42 pm

Politicians and Legislation, Government Advisors and similar eg. N Ferguson - how can someone who has made such gross errors in his work and is now doing the same again with his "predictions" re numbers of people/deaths, with this so-called "mutated" COVID,.

There used to be transparency and ACCOUNTABILITY. Boris Johnson I won't upset myself with his gross errors of judgement in many areas.

That the technocracy have been able to dictate to the World what or not can be, is never to be allowed again. Lack of the realities by Legislators and forward thinking in not allowing behemoths' to form, and then placing forward thinking legislation into place, and treat the Fauci Gates Schwab Koch Clintons and others as the criminals they are.

White collar criminals are treated with kid gloves in terms of processes of Law, Punishments by Law for their gross, money-making actions that do such obscene damage to Humanity. All proceeds should be taken and given as compensation to the victims - throughout the World.

The LEGAL world, for a very long time, has needed to be under a most intense spotlight, and held accountable in so many ways.

Deirdre

28 December 2020 at 12:22 pm

As Ferguson has previously demonstrated, his models are far from being crystal balls - and in this case, he, like everyone else, cannot predict the interactions of these latest variants with their hosts. That will require the passage of time. I have yet to give up on either the scientific or legal worlds - I think it's just a matter of time before both help get us back into a better state of equilibrium. And let's hope that happens some time before the end of 2021!

29 December 2020 at 9:16 am

Things are becoming clearer - the W H O is now prepared to blatantly re-write history - New Science for the New Normal

Whereas the human race has evolved and survived the challenges presented by microbes through the millenia - this, the advantage conferred by natural processes - is now judged of nil value. Herd immunity cannot be achieved through natural resilience - but ONLY through vaccination.

https://www.aier.org/article/who-deletes-naturally-acquired-immunity-from-its-website/

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences