Content Sections

By Rob Verkerk PhD

Founder, executive and scientific director, ANH-Intl

It’s now 2 weeks ago that we released the ANH Food4Health Plate. To say that it has stimulated interesting discussion is an understatement. Common responses have ranged between “absolutely right” to “don’t agree with the 5 hours between meals” to “not enough fat” – and many things in between.

We’ve spent a lot of time talking things through with various people – and this has stimulated the need for this follow-up piece.

It’s becoming apparent that the collaboration between governments and industry that is attempting to counter spiralling metabolic diseases in our society, ranging from type 2 diabetes and obesity, through to cardiovascular diseases and some cancers, is not achieving its objective. That's partially down to the fact metabolic disease is multi-factorial, multi-faceted and so inherently complex. As the McKinsey report showed last year, dealing with obesity alone requires a wide range of different interventions, some of which, say those relating to developing a healthy gut microbiome, have yet to be agreed on the basis of consensus science.

The failure of existing approaches is born out by the epidemiology which shows a continuous upward spiral, one that’s predicted to increase at least to 2035.

There's further failure in getting consensus between what we might call independent scientists and government scientists and Big Food. An example of this is the lack of acceptance that high sugar and refined carbohydrate intakes are central to insulin resistance, the precursor to type 2 diabetes.

Governments are concerned, there is no doubt. But in our humble opinion there is little likelihood that most of the top-down strategies which focus on limited aspects of the problem, such as discouraging energy (calorie) and saturated fat intake, will make much of a difference. Why do we say this? Because there is no persuasive underlying science that suggests this will work. There is also growing evidence that previous strategies of this type fail – over and over again. The 5-year EU obesity strategy is one such failure.

In the UK, the system that’s being rolled out with great gusto is the Public Health Responsibility Deal. It’s about government (the guys in charge) and Big Food (the guys selling the wares that are making people ill) working in partnership to make us all healthy again (bless them!). Among the Responsibility Deal’s broadcasted successes are Big Food’s reduced sugar breakfast cereals, reducing the amount of alcohol on the market by a billion units, tips for healthier eating at take-aways, and Britvic’s decision to remove its full sugar Fruit Shoot from the market. They all help – a bit, but not enough.

History tells us these kinds of top-down changes don’t dramatically change people’s approach to nutrition and activity sufficiently to create a turn-around in health. That brings us to guideline food plates – another compromise that has been decided between industry and government.

Guideline Food Plates: yes or no…

In our recent feature Rethinking your food choices for 2015, we showed you the UK, US and our own Food4Health food plate.

Anyone who says “they’re all useless” would pique my interest. Why? That’s because no one plate will suit everyone. Our genetic and epigenetic backgrounds, as well as our levels of activity, stress and lifestyles, all demand different food compositions. Even any one individual — say you or me — shouldn’t eat the same composition of foods and macronutrients (protein, fats and carbs) every day, day in day out. That’s because our activity pattern, stress and other elements of our lifestyle are, or should be, in a continuous state of flux.

This brings us to two key points: metabolic flexibility and resilience. These are the real markers of health. Metabolic flexibility refers to the capacity to adapt to, and burn (oxidise), whichever fuel is available. Someone who has developed metabolic flexibility can therefore handle a more variable diet and can burn fats effectively, these being the richest source of energy for the body. Physiological resilience refers to your ability to respond and recover from physiological, metabolic, immunological or lifestyle stress. Someone who is resilient, is someone who can regain equilibrium—or homeostasis—more quickly than someone who may be free from clinical symptoms of disease, but ultimately, lacks this supreme level of vibrant, resilient, and ultimately, adaptive health.

There are a few principles that are common among those who obtain this state of metabolic flexibility and resilience. These include:

- They are keto-adapted and are able to readily burn fats for fuel

- They regularly practice caloric restriction through fasting between meals. This is quite different from just eating fewer calories every day, little and often!

- They are physically active

- Their diet is anti-inflammatory and loaded with phytonutrients from the 6 main colour groups of the phytonutrient spectrum

- The bulk of their diet, in terms of its energy contribution, does not come from carbohydrates - wholegrain or otherwise!

- They show no signs of metabolic syndrome or insulin resistance, either in muscles or in other tissues and therefore have ideal or near-ideal body compositions (muscle/adipose/visceral fat ratios)

- They have modified their nutritional intake, eating habits and lifestyle in such a way as to largely offset any disadvantageous genetic limitations or polymorphisms they may carry

- Their diet and activity levels create psychoemotional flexibility too, meaning more emotional balance – and yes, happiness!

In this much broader context—one that is almost never raised in the dialogue between governments and the food industry—we believe it is useful to have a notional ‘plate’ that helps people to move in the direction of metabolic flexibility and resilience. That’s partially because people are looking for some kind of a guideline, and also because it’s necessary to offer an alternative to the ones proffered by governments, which in our circles, are often somewhat cynically referred to as ‘diabetes plates.’

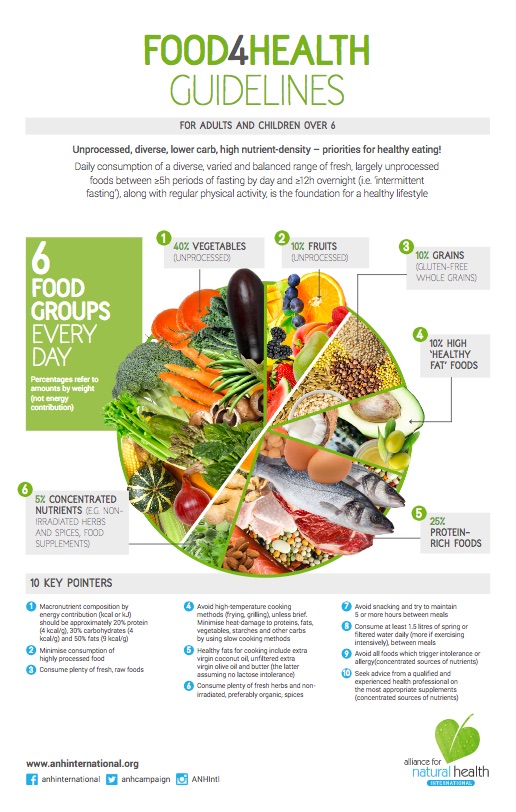

With this background, we are ready to review the Food4Health plate (Download PDF).

Clarifying the Food4Health Plate

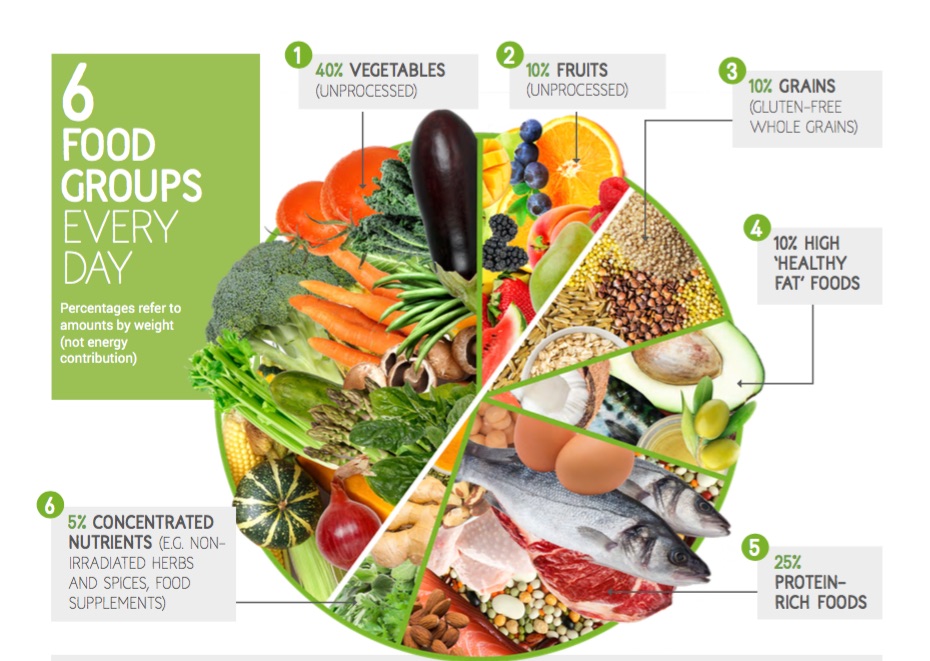

You’ve got the point: this is a guideline plate, not something you follow to the letter. There have been a lot of people confusing the macronutrient composition of our plate, which is based on fresh weight of the food, and most other representations that refer to the relative energy contribution of each macronutrient, namely protein, fats and carbs.

In essence, our plate looks like this by weight:

- 40% unprocessed veg

- 10% unprocessed fruit

- 25% high protein foods

- 10% healthy fat foods

- 10% whole grains (gluten-free)

- 5% herbs, supplements, etc

We’ve factored in various food combinations that fit this pattern and a typical macronutrient composition—still by weight—looks something like this:

- 32% protein, mainly from meats (where present), veg, nuts/seeds, cheese/dairy (where present), etc.

- 28% fats, mainly from oils, seeds, nuts, oily fruits like avocado, and from meats (where present)

- 40% carbohydrates, mainly from veg, fruits and grains (where present)

Now, if you look at the above ratios in terms of their energy contribution you have to take into account the energy derived from each macronutrient based on the accepted premise (and that’s another discussion!) that each gram of protein and carb yields 4kcal (calories) respectively, and fat yields a whopping 9kcal per gram. This simple premise combined with the (misplaced) view that it is just excess caloric excess that is driving the obesity epidemic inspires governments to push low fat diets. Implicit with this obsession to drive the public to consume fewer calories, are two more, even more deeply misplaced assumptions: a) that all calories behave in similar ways in each person’s body and b) that the quality of the food and other nutrients contained within a given calorie of food are identical.

Anyway, looking again at the above macronutrient ratios for the Food4Health Plate, but now from an energy contribution viewpoint, we get the following ratios:

- 24% protein

- 46% fat

- 30% carbohydrate

This contrasts with UK guidelines that suggest 50% of energy should come from carbohydrates, whereas we are suggesting around 50% should come from fat.

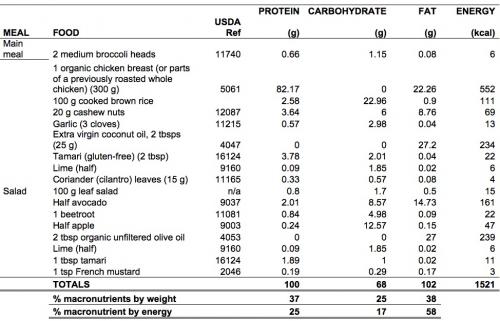

Example plate

Following is a main meal including a salad that roughly fits the Food4Health Plate guideline. It includes some lean protein, healthy fats, lots of veg, a small portion of brown rice, some fruit and some nuts. What you’ll see is that more than half (57%) of the energy in it comes from fats and les than 20% comes from carbs. A day's eating, rather than just this one meal, would likely include a bit more fruit and veg that would likely bring the carb contribution closer to the 30% mark mentioned above. Add another handful of unsalted tree nuts (e.g. almonds, cashews, macadamia, brazil, etc) to the equation, and it would skew it even more further in the direction of fats. Is that bad? Hell no! And that’s really one of the main points we’re making with our plate. The government plates are still oriented far too strongly in the direction of carbs and away from fats. Put simply, it's the wrong way around!

Table 1. Example plate, roughly consistent with the ANH Food4Health Plate guidelines

So when you look at our one-meal plate in terms of weights, it might look like a low fat plate. But it isn’t, as you’ll see from the calculation according to energy contribution. There’s a fair bit of healthy fats coming in from all the food groups and because of the energy contribution of fats, more than doubling that of proteins and carbs, you end up with a relatively high fat content. If you are extremely active, being for example an endurance athlete, you might end up benefiting from closer to 80% of your energy from fats! But you need to be keto-adapted, highly active and have no insurmountable genetic impairments in your ability to metabolise fats to do that.

So our plate, like any plate, is a compromise, for the non-existent average person.

So much more than what’s on your plate

Another elephant in the room (there are numerous elephants there in case you hadn't noticed) is the issue of how and when you eat. We don’t have the space to cover the intricacies of these arguments in this piece, suffice to say how you prepare your food, how you chew it, when you eat, how long your leave between meals, along with your genetic background, lifestyle, physical activity and nutritional needs, are all crucial to deciding how the food will interact with your metabolism.

But if there’s one additional message specific to nutrition that is stronger than any other, we’d argue it is the need to fast regularly. That means daily. And the easiest way of doing this is to try to fast 12 hours overnight and 5 hours between meals. This has been a central plank to the Metabolic Balance programme that has helped many tens of thousands to reset their metabolism and endocrine system, helping people to emerge from insulin resistance, pre-diabetes, metabolic syndrome and even type 2 diabetes. Eating little and often, as recommended by the vast bulk of dieticians, simply pushes people into insulin resistance and a downward spiral of associated metabolic diseases that now plague our society.

Another elephant? The relationship between eating and physical activity. Getting it right is a minefield, especially taking into account patterns of activity and genetic variations between individuals. But we have all learned a great deal about this complex interactions from successful sports physiologists and nutritionists, and a few central themes are beginning to emerge that apply to most people. We'll cover more on this in another piece.

Next week, however, we’ll give you more input on what we've been learning in recent years about food frequency, fasting, enhancing digestion and when you should eat in relation to bouts of moderate or intense physical activity. So stay tuned...

Epilogue

Oh, another question we’ve been asked in many different ways: how would you describe your Food4Health Plate, “is it a high protein, low carb plate, for example?”

We’ve scratched our heads and not come up with any very short, punchy descriptors, other than the 'Food4Health Plate'. But we have no trouble giving long form descriptors. One such descriptor that puts it neatly (note sarcasm) in a nutshell is: “A largely unprocessed, relatively low carb/high complex carb, low glycaemic, moderately high fat and high protein, anti-inflammatory, pro-mitochondrial, longevity plate.”

But please remember, it’s just a rough guideline and a starting point, from which to help you on your journey to being a keto-adapted, super-resilient, metabolically flexible and well being.

Read:

8th April 2015 ANH-Intl’s four plate shoot-out

12th Feb 2015 ANH-Intl Feature: Fuel efficiency and the Food4Health Plate

21st Jan 2015 ANH-Intl Feature: Re-thinking your food choices for 2015

Comments

your voice counts

29 March 2016 at 1:01 pm

A great article! Whatever Dr. Verkerk muses on is always guranteed to be an interesting read! This should be a compulsory read for the NHS staff! ;)

11 September 2016 at 2:28 pm

Raw Vegan is the perfect diet . Dead foods make Dead Bodies ! Stop Acidification , Alkalize with greens and Magnesium Salts. Dangerous Grain Damage . .

Your voice counts

We welcome your comments and are very interested in your point of view, but we ask that you keep them relevant to the article, that they be civil and without commercial links. All comments are moderated prior to being published. We reserve the right to edit or not publish comments that we consider abusive or offensive.

There is extra content here from a third party provider. You will be unable to see this content unless you agree to allow Content Cookies. Cookie Preferences